Acknowledgments

This book would never have been written if my grandchildren had not asked me to tell them where I grew up and what happened to me. They had to write school essays on immigrants. My family knew me as an American business executive and an ocean sailor, and by 1990 my youth in Hitlers Germany had receded far into the past. I rarely thought about my life then more than fifty years ago, and we never talked about it. But now, when my children, their spouses, and my second wife saw what the grandchildren wrote, they urged me to write my life story for the family.

As I started to write, in 1993, I received an invitation, on the occasion of the eight-hundredth anniversary of its founding, to visit Gardelegen in Germany, where I was raised. My son Michael, his wife, Katja, and my wife, Barbara, wanted me to take them along, to see where I had come from. Michael then made a video of our visit and my early life in Gardelegen.

Soon after, Leslie Gelb, then president of the Council on Foreign Relations, invited me to speak to that organization, and he and Henry Grunwald, former editor of Time magazine and American ambassador to Austria, urged me to write about my life. It would not have happened without their encouragement. I thank them.

While I was trying to shape up one of many drafts, the secretary general of the American Jewish Committee (AJC), David Harris, asked me whether I would speak in Germany, and he then arranged for the Evangelical Church of Germany to be a cosponsor with AJC. My presentations at a premier Berlin cathedral and as the inaugural speaker, following Germanys president, at the Nrnberg Dokumentationszentrum, were prominently reported by the German press and also led to numerous TV appearances. Now a Frankfurt house offered to publish my book in German, sight unseen. It took a year to convert my English draft into the German best seller Mehr als ein Leben.

The book was introduced by the German authority on the trial of the Nazis, Nuremberg chief judge Klaus Kastner, in the same courtroom where I had worked. Afterward I returned to complete the draft of the present book.

First I want to thank Barbara, my wife, who allowed me to use the carpet of my office as a filing cabinet, while I worked without a secretary. Far more important, she has been an invaluable constructive critic, and her insights have been most helpful. My daughter, Ann, a public relations professional, has made sure that my appearances were properly announced, and her editorial comments were highly important to me in the development of the manuscript. While I thank her and all of my children and grandchildren, many of whom accompanied me to Germany, I must single out my son Michael and my granddaughter Sara, who watched over me on my last trip, after illness forced me to travel in a wheelchair.

Special thanks are also due Lloyd G. Schermer, on whose board I served for eighteen years, who encouraged me, and Lewis Smoler, my dentist, and his wife Carol, who read and critiqued several drafts with the same attention he lavishes on my root canals.

Many other friends have been very helpful and patient with me, a first-time author. I thank you.

Thanks are also due to Bill Hanna, my agent, and Jeannette Seaver, my editor, without whose efforts this book would not have been published.

EPILOGUE

Nuremberg Fifty Years Later

T HE AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE and the Academy of the Evangelical Church (the largest German Christian denomination) sponsored me to speak in 2002 at a principal cathedral in Berlin. To my astonishment, the German national press and broadcast media reported prominently my youth in Nazi Germany, my adventures as a teen all over the world, my personal conversations with Nazi defendants and witnesses at the Nuremberg trials, my life in America, my sailing adventures, and my visits to Gardelegen. In December of that year, I was invited to return to Nuremberg. A new museum and educational center, the Dokumentationszentrum, tracing the rise and fall of Hitlers Germany, had just been dedicated by Germanys president, Johannes Rau. I was honored to be its first speaker.

To refresh my memory I had asked to visit the courtroom before my speech. It was 5 P.M., April 24, 2002, in Nuremberg, sixty-one years less two days after I had arrived in America.

My escort opened the massive wooden door, shoved his hand under my elbow, and pushed me gently forward into Saal 600, the scene of the Nuremberg trials.

Why is it so dark in here? I asked.

I heard muffled voices but saw no faces. Suddenly camera flashes and video lights blinded me. Someone opened the curtains, and I saw reporters with pencils poised over notebooks, audio engineers with microphones on booms marching toward me.

Surprise!

Instead of the quiet visit to the courtroom of Nuremberg that I had requested, unbeknownst to me, my hosts had arranged a press conference!

You were the chief interpreter of the American prosecution at the trials here of major Nazis in 1945? someone shouted.

Yes, I said.

Show us where the Nazis were sitting? Where were the judges, the prosecutors? Where were you? The questions tumbled over each other.

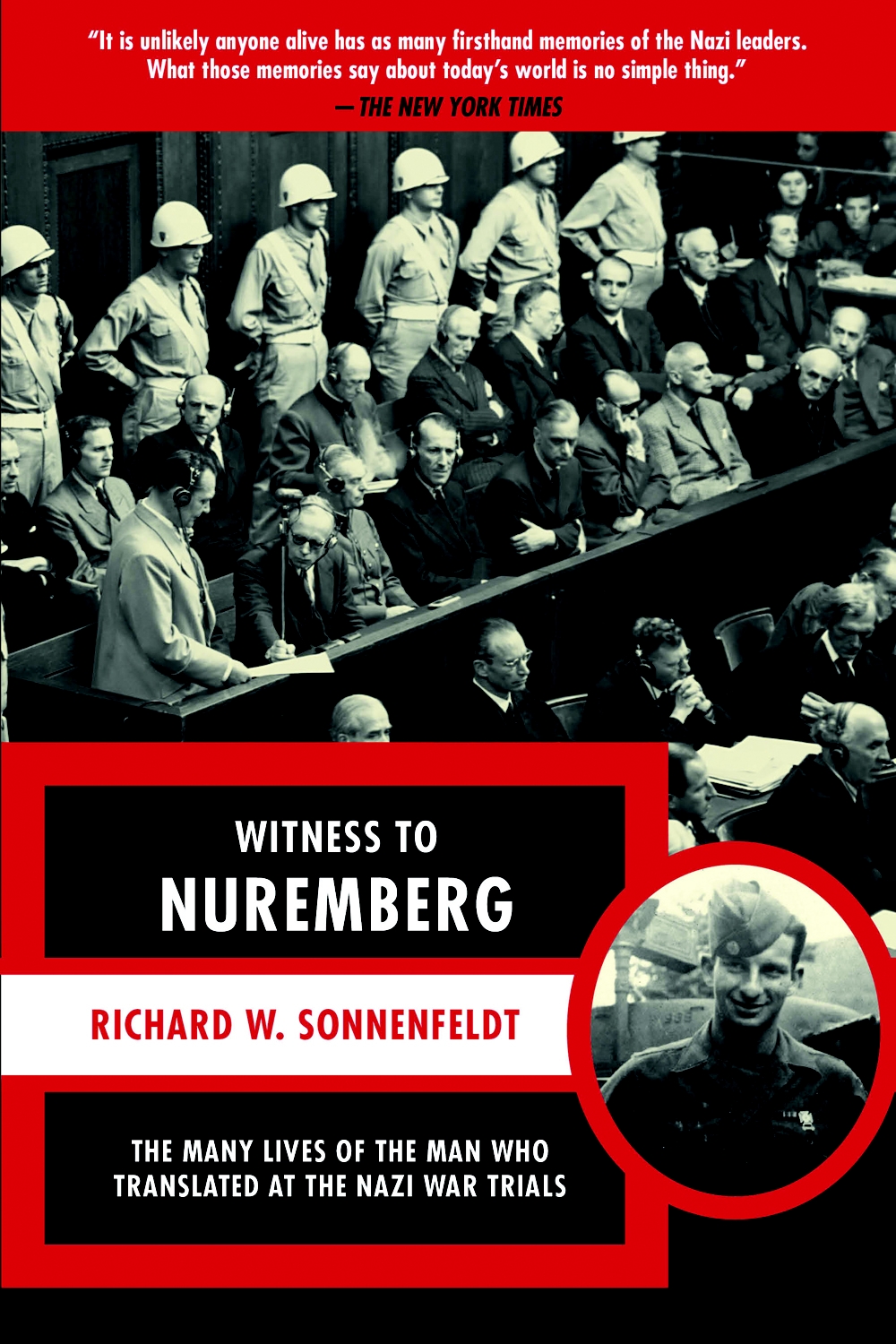

Every detail of the 1945 courtroom was etched in my memory, but now the rooms layout was different. There, at the left side of the room, the defendants had sat in two rows, and standing behind and around the defendants had been young American military police in gleaming white helmets, with white gloves and belts, trying to look alert and immobile at the same time.

I pointed to the spot where Justice Jackson, the chief American prosecutor, had stood as he said, We must also be prepared that this court may find some of the defendants not guilty. Otherwise we might just as well hang them all now!

Gone was the glass cage up there by the back wall where the court interpreters had strained to catch every word. I explained,

I was the chief interpreter and an interrogator for the American prosecution, and I spent hundreds of hours with defendants and witnesses in secluded interrogation rooms. But I was not a court interpreter, who had to listen to the defendants for months right over there but never had the opportunity to talk to them, face to face, one to one, as I did.

And what was your job later, in the courtroom?

To verify that witnesses and defendants made the same statements in court as those they made in pretrial examinations.

Someone asked, What did the trials accomplish?

For crimes they committed in the name of hate, race, and rabid nationalism, eleven of the most senior Nazi leaders were sentenced to hang by the neck. Seven others went to prison, and three were exonerated. But something even more important than punishment of the guilty was accomplished. The Nazis trickery in assuming total government power, their killing and torturing of Germans who opposed them, the killing of Jews, and the ruination and enslavement of the nations they attacked were all documented with their own papers, signed by their own hands, and the testimony of their subordinates. SS killers testified how they had murdered tens of thousands, a few at a time, before the ovens of Auschwitz made such retail killings obsolete. The world would never have known the full and terrible extent of the Holocaust without the record of these trials, or have seen proof of the incredible duplicity and unbounded egotism of the Fhrer for whom millions of Germans died. The history of the Thousand Year Reich, which lasted just twelve years, was written in the Nuremberg trials, making it impossible forever to deny or explain away this dreadful chapter of the German past.