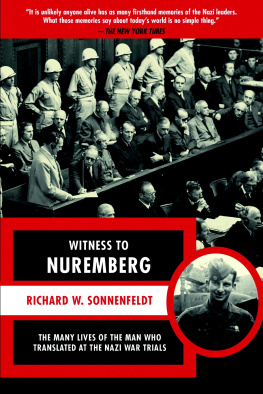

The International Military Tribunal in session, summer 1946. National Archives

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF, INC .

Copyright 1992 by Telford Taylor

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Taylor, Telford.

The anatomy of the Nuremberg trials: a personal memoir / by Telford Taylor.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-0-307-81981-9

1. Nuremberg Trial of Major German War Criminals, Nuremberg, Germany, 19451946. 2. International Military Tribunal. I. Title.

JX5437.8.T39 1992

341.69026843324dc20 9142605

v3.1

To Toby Golick

Contents

Photographs follow .

Introduction

In the spring of 1945, I was a reserve colonel in the intelligence branch of the United States Army. My duties had to do with information derived from the deciphering of enemy messages, the product of which in recent years has become publicly known as Ultra or Magic. My base of operations was in southern England, but I had been given general responsibility for the security of Ultra and its distribution to the principal American army and air headquarters in Western Europe, and this required frequent trips to the Continent.

By April, it had become apparent that the Third Reich was in its death throes and that a total Allied military victory in Europe was imminent. Accordingly, early that month I embarked on what I expected to be, and was, the last of my circuits around the commands that we were servicing. On about April 20, en route to General Pattons headquarters at Erlangen in northern Bavaria, I drove through nearby Nuremberg, where I had never been before.

Little of its famed beauty was to be seen. The city had been heavily bombed by the Royal Air Force in January and March and taken, only after heavy fighting during the past few days, by General Wade Haislips XV Corps. Most of the city lay in ruins, parts were still burning, and the streets were so choked with rubble that I could hardly get through.

Returning to England a week later, I was met at the airfield by my colleague Lieutenant Colonel Ted Hilles (in peacetime a distinguished professor of English literature at Yale), bringing a message to me from my superiors at the War Department in Washington. Its burden was that Robert H. Jackson, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, had been appointed by President Truman to represent the United States as chief prosecutor at a projected international trial of war criminals, to be held as soon as possible after the victorious end of hostilities. The message went on to say that Justice Jackson was assembling a legal staff to assist him and had asked that the War Department make me available for that purpose.

The tone of the message suggested that the departmental authorities would be pleased if I acceded to the Justices request, but it was made clear that the decision was up to me. The proposition gave me plenty to think about, both professionally and personally.

I had graduated from Harvard Law School in 1932 and during the next ten years had held a succession of federal government legal positions. In 1939 and 1940 I had served briefly as a Special Assistant to the Attorney General. During those years Jackson had been Attorney General until his appointment to the Supreme Court. I had met him a few times, heard him argue several cases, and had myself argued one case before the Supreme Court after Jackson had become a member. I was well aware of and shared the high opinion of his character and ability which was generally held. He was a man under whom I would be proud to serve, and I had no doubt that his mission would be a unique and challenging one.

On the other hand, nothing in my legal education or experience had involved international law in general or war crimes in particular; to me it was unknown territory. Furthermore, I had not given law a thought since going into the army in 1942, and my military duties had taken me far afield from cases and courts. I had never been in private practice and had intended, upon leaving the army, to return to New York to get some badly needed experience in the private sector and develop an independent footing as a lawyer. At the age of thrity-seven, this was a step which should not be long postponed.

As for the military side of the matter, it was plain that the Germans would surrender in a few days and that my own mission in Europe was as good as finished. But the war against Japan was not, and it was feared that a massive invasion of the Japanese mainland might be necessary to bring about a surrender. Many of the senior American officers, particularly the regulars, were anticipating reassignment to the Pacific theater. I myself had expected that I would soon be recalled to the Pentagon building and perhaps sent to the other war. I had no idea how near Japan was to defeat or whether there was a place for me in the Pacific intelligence structure. But I was somewhat reluctant to get out of uniform until the war as a whole was over, and therefore I decided to ask permission to return to Washington before making a final decision about Jacksons invitation.

Personal feelings and problems moved me in the same direction. My marital situation was in disarray in consequence of an intense relationship with a young Englishwoman who was married to a British officer of my acquaintance. Returning to my home in Washington might at least ease immediate tensions and allow time to try to sort things out.

The Pentagon readily approved my request, so I said my farewells in England and flew to Washington, arriving home about May 22. During the next few days I visited Jacksons staff headquarters and discussed the situation in the Pacific theater with my superiors in the intelligence division, particularly with Colonel Alfred McCormack, in peacetime a law partner of John J. McCloy, the Assistant Secretary of War. I knew that McCormack was as well informed and otherwise equipped as anyone to assess the prospects of the war against Japan. Whether or not he was in on the secret of the atom bomb I do not know, but he told me categorically that the Japanese military situation was hopeless, that the Emperors advisers knew it, and that intercepted Japanese diplomatic messages revealed their anxiety to make peace. He thought it highly unlikely that an invasion of the Japanese mainland would be necessary or that the war would last much longer.