Soviet Judgment at Nuremberg

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Francine Hirsch 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress.

ISBN 9780199377930

eISBN 9780199377954

To Mark

Contents

International Institutions

| IADL | International Association of Democratic Lawyers |

| IMT | International Military Tribunal |

| UNWCC | United Nations War Crimes Commission |

American Institutions

| JAG | Judge Advocate Generals Department of the U.S. Armed Forces |

| OSS | Office of Strategic Services |

German Institutions

| Gestapo | Geheime Staatspolizei; Secret State Police |

| RSHA | Reichssicherheitshauptamt; Reich Central Security Office |

| SS | Schutzstaffel; Protection Squadron |

| SA | Sturmabteilung; Storm Battalion, Storm Troopers |

| SD | Sicherheitsdienst; Security Service |

| SiPo | Sicherheitspolizei; Security Police |

Soviet Institutions, Places, Territorial Designations

| NKVD | Narodnyi komissariat vnutrennikh del; Peoples Commissariat for Internal Affairs (until March 1946); Ministry of Internal Affairs |

| NKGB | Narodnyi komissariat gosudarstvennoi bezopasnosti; Peoples Commissariat for State Security (until March 1946); Ministry of State Security |

| RSFSR | Rossiiskaia Sovetskaia Federativnaia Sotsialisticheskaia Respublika; Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic |

| SMERSH | Smert Shpionam!; Death to Spies!, Chief Counterintelligence Directorate |

| SSR | Sovetskaia Sotsialisticheskaia Respublika; Soviet Socialist Republic |

| SVAG | Sovetskaia voennaia administratsiia v Germanii; Soviet Military Administration in Germany |

| Sovinformburo | Sovetskoe informatsionnoe biuro; Soviet Information Bureau |

| TASS | Telegrafnoe agentstvo SSSR; Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union |

A Note About Soviet Institutions and Name Changes

In March 1946 all peoples commissariats were renamed ministries. I use the names Ministry of Internal Affairs, Ministry of State Security, and Ministry of Foreign Affairs throughout the book (even for the period before March 1946 when the institutions were officially called commissariats).

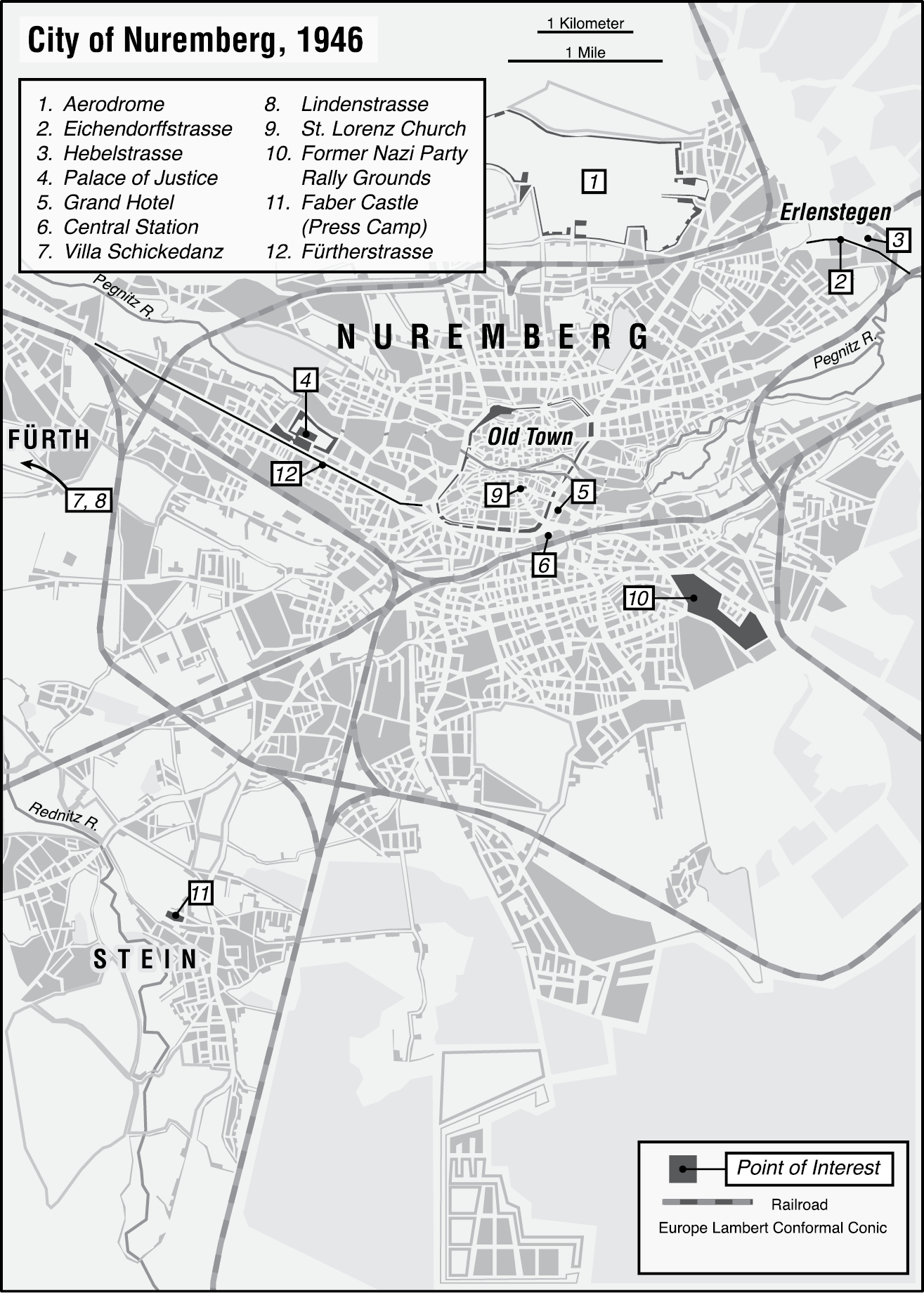

Map 1 City of Nuremberg, 1946.

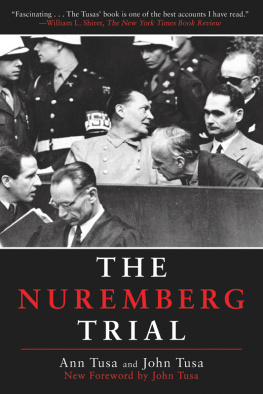

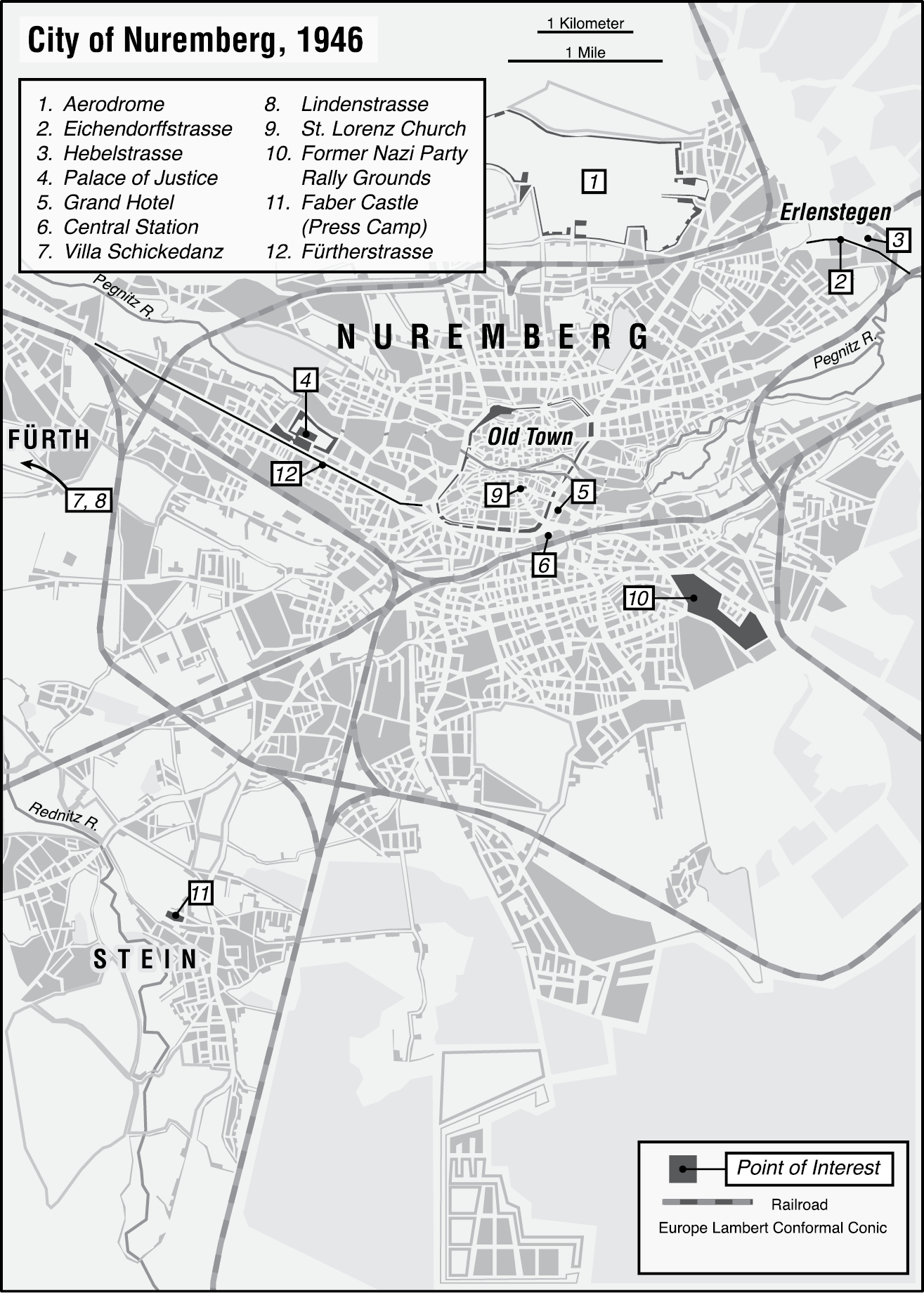

In november 1945, roughly six months after the end of the Second World War in Europe, the International Military Tribunal (IMT) convened in the Palace of Justice in the city of Nuremberg, in the American zone of what had been Nazi Germany. The flags of the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and France flew over the entrance to the imposing sandstone building, and honor guards from all four countries stood at attention outsidevisible reminders that this trial of the former Nazi leaders was being held by the four military powers occupying Germany.

Nuremberg was rich with symbolic significance. The city had been the cradle of the Nazi movement, the site of choreographed mass ralliesrecorded for posterity in Leni Riefenstahls Triumph of the Willat which Adolf Hitler had announced the Third Reichs race laws and roused millions of followers with the promise of a resurgent Germany. It had also been one of the last holdouts of German forces, the setting of one of the final battles of the war in Europe. This was a fitting place for a postwar reckoning.

Among those who came to observe the trial was the Soviet filmmaker Roman Karmen, a special correspondent for the Soviet press who was tasked with documenting the proceedings. Making his way through the city in a car on the day of his arrival, Karmen was struck by the devastation. You do not see one intact structure in Nuremberg, he observed. It is sheer ruins. Karmen had spent the last few years as a cameraman embedded with the Red Army, shooting footage in Leningrad, on the Don, and on the Belorussian front. He had seen what war could do. Even so, he was taken aback by what

After dropping off his luggage at the Press Camp, located southwest of the city, Karmen headed directly to the courthouse. He was in a hurry. His arrival in Nuremberg had been delayed because of bad weather. It was already November 22; he had missed the first two days of the trial and did not want to waste any more time. His car turned onto the Frtherstrasse, one of the few streets that had escaped significant damage. There, behind cast-iron gates, stood the Palace of Justice. Four stories high and built early in the century, it appeared relatively unscathed by the war. Thousands of German prisoners of war had been put to work by American occupation forces to fill in bullet holes and otherwise repair the building. Noticing the Soviet soldiers in the honor guard, Karmen felt a surge of pride, recalling the Red Armys valorous path from Stalingrad to the Volga to Moscow to Berlin.

Figure I.1 The Palace of Justice in Nuremberg, the site of the International Military Tribunal, ca. 19451946.

Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Harry S. Truman Library. Photographer: Charles Alexander.

Inside the Palace of Justice, Karmen marveled at the mixture of grandeur and functionality. The courtroom itself had been demolished and expanded to include space for the eight judges, the four teams of prosecutors, the defendants and their attorneys, and the hundreds of representatives of the press who now crowded the back of the room. A special booth had been built for the interpreters behind the witness box; an upstairs gallery had been added for spectators. The air smelled of fresh wood and paint. A bronze bas-relief of Adam and Eve and the serpent, original to the building, hung on one of the walls. American military police in white helmets stood guard. Directly across from the judges bench was the dock; Karmen immediately recognized both Hermann Goering and Rudolf Hess among the defendants. Later, in the thick of the trials, Karmen would recall the great satisfaction he had felt at this precise momentknowing that this was the place where the peoples of the world would judge the band of fascist hangmen. This was where he would spend the next ten months filming the trials for posterity.