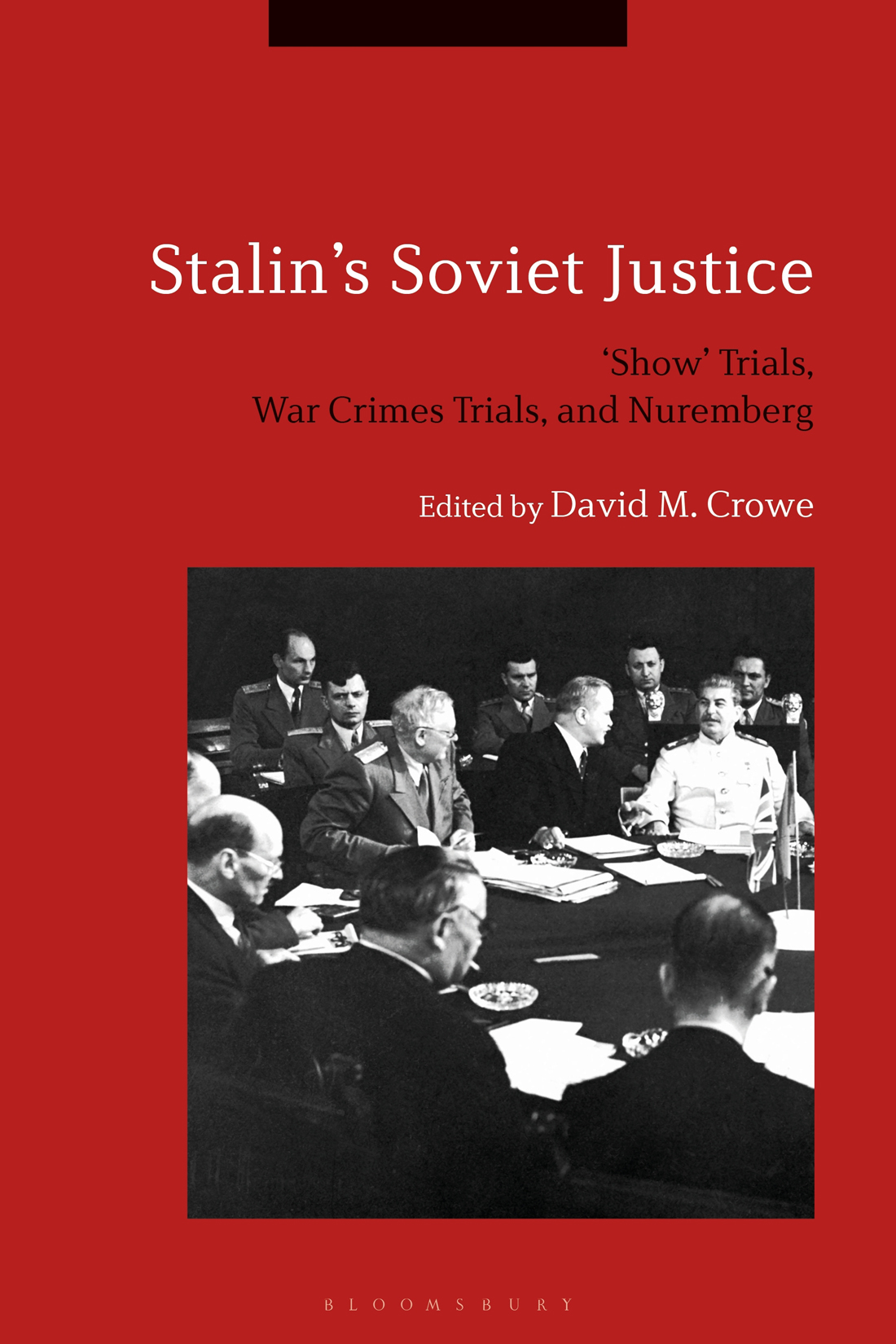

Stalins Soviet Justice

Alexander Victor Prusin

(19552018)

Of Blessed Memory

Stalins Soviet Justice

Show Trials, War Crimes Trials, and Nuremberg

Edited by David M. Crowe

Contents

David M. Crowe is a presidential fellow at Chapman University and Professor Emeritus of History and Law at Elon University, where he held a joint appointment at the School of Law and the Department of History. His most recent books include Da tu-sha gen-yuan li-shi yu yubo (The Holocaust: Roots, History and Aftermath) (2015), Germany and China: Transcultural Encounters since the Eighteenth Century (with Joanne Cho; 2014), War Crimes, Genocide, and Justice: A Global History (2014); and The Holocaust: Roots, History, and Aftermath (2008). His books have been translated and published in Chinese, Dutch, German, Japanese, Polish, and Ukrainian.

Jeremy Hicks is Professor of Russian Culture and Film at Queen Mary University of London, UK. He is the author of Mikhail Zoshchenko and the Poetics of Skaz (2000), Dziga Vertov: Defining Documentary Film (2007), and First Films of the Holocaust: Soviet Cinema and the Genocide of the Jews, 19381946 (2012), which won the ASEEESs 2013 Wayne C. Vucinich Prize for the most important contribution to the field of Slavic, East European, and Eurasian studies.

Francine Hirsch is Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA. Her first book, Empire of Nations: Ethnographic Knowledge and the Making of the Soviet Union (2005), received the 2007 Herbert Baxter Adams Prize of the American Historical Association, the Council for European Studies 2006 Book Award, and the 2006 Wayne S. Vucinich Prize of the ASEEES for the most important contribution to Russian, Eurasian, and East European studies. Her forthcoming book, Soviet Judgment at Nuremberg , will be published in 2019.

Douglas Irvin-Erickson is Assistant Professor of Conflict Analysis and Resolution, Director of the Genocide Prevention Program, and Fellow at the Center for Peacemaking at the School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution at George Mason University, USA. He is the author of Raphal Lemkin and the Concept of Genocide (2016) and the editor of Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal , the official publication of the International Association of Genocide Scholars.

Valentyna Polunina is an affiliate member of the University of Heidelbergs Cluster of Excellence Asia and Europe in a Global Context program, Germany. She received her doctorate from the University of Heidelberg. Her dissertation deals with the trial of Japanese war criminals and Japans biological warfare program at Khabarovsk in 1949. Prior to her current position with Germanys Der Spiegel in Washington, D.C., she taught in the Russia-Asia department at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Germany.

Thomas Earl Porter is Professor of Modern European History at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University in Greensboro, NC, USA. He has written extensively on the government and politics of late imperial Russia, the role of Russian public organizations during the First World War, the failure of Russian liberalism, and the fate of Soviet POWS during the Second World War. His most recent work is Prince George L. Lvov: The Zemstvo, Civil Society, and Liberalism in Late Imperial Society (2017).

Alexander Victor Prusin is Professor of History in the Humanities Department of the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, Socorro, USA. He has authored a number of articles and three books: Nationalizing a Borderland: War, Ethnicity, and Anti-Jewish Violence in East Galicia, 19141920 (2005); The Lands Between: Conflict in the East European Borderlands, 18701992 (2010); and Serbia under the Swastika: A World War II Occupation (2017).

Irina Schulmeister-Andr is a judge of the District Court Gieen, Germany. She was a scholar at the Max Planck Institute for Legal History in Frankfurt am Main, where she began her research for her doctoral thesis on the role of the Soviet Union in the Nuremberg IMT trial.

David M. Crowe

War has had a dramatic, and at times, devastating impact on Russia over the past few centuries. After the Napoleonic invasion in 1812, Alexander I, who once toyed with the idea of modest Enlightenment-era reforms, reverted to what would become standard political behavior for many of the tsars in the late imperial perioda rigid autocracy designed to protect the imperial system from real and imagined forces that threatened its power and stability. But what Alexander I, Nicholas I, Alexander III, and Nicholas II could never do was to halt the revolutionary fervor that was sweeping into Russia from Europe in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In some ways, one could argue that Lenin and Stalin, who dominated Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1953, faced similar challenges, though the nature of the threats to their power and stability were driven, at least during the first decade of Bolshevik rule, by power struggles within the upper echelons of the Communist Party about the ideological and practical direction of Soviet rule.

Once Stalin won his power struggle against his principal rival, Leon Trotsky, he adopted new campaigns to collectivize Russian agriculture and dramatically increase industrial production. He decided in the late 1920s to use show trials as one of the ways to respond to growing domestic opposition to both programs. The show trials, extralegal proceedings that bore modest resemblance to more traditional Western-style trials, were carefully orchestrated to convince the public of the dire nature of such threats. Thematically, Stalin used them to highlight his fears about an ongoing threat of domestic and international forces determined to destroy the Soviet state. Wrapped in a faade of legality, the show trials were well-crafted propaganda exercises designed partially to rally a nation to support Stalins goals.

Show trials in Russia can be traced back to that one bright spot in late imperial historythe reign of Alexander II, the tsar liberator. Alexander II was not a visionary liberal but a pragmatist who realized that Russias defeat in the Crimean War (18531856) was based on its economic and military backwardness vis--vis its principal opponentsEngland and France. Soon after he came to power, Alexander II initiated a series of reforms that addressed not only the single biggest factor for such backwardnessserfdombut also the military, law, and the structure of civil society.

As his reform program unfolded, it spurred new discussions among enlightened Russian thinkers such as Alexander Herzen and Boris Chicherin about different approaches to the transformation of Russian society. Some, like Mikhail Bakunin and Serge Nechaev, called for more radical, violent approaches to change that, according to

Chapter 1

David M. Crowe notes in Late Imperial and Soviet Show Trials, 18781938 that this included plans to assassinate prominent government officials to create uncertainty and instability throughout the country. By the 1870s, a new generation of revolutionaries decided to act more boldly, even if such actions led to their executions. One of them, Vera Zasulich, a young revolutionary with strong ties to Nechaev, was motivated not only by a series of government trials of several hundred revolutionaries in 1877 and 1878 but also by stories about the public flogging of another revolutionary, Alexei Bogolyubov, in St. Petersburgs Kresty prison. The beating had been ordered by Dmitri Trepov, the governor general of the city, who was offended when Bogolyubov refused to tip his hat when Trepov walked by during an inspection of the prison.