Introduction

T he trial conducted by the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg, Germany, from November 1945 until October 1946 was one of the most significant in the annals of jurisprudence. For the first time in history, the men being tried had not personally committed the crimes and atrocities of which they had been accused, but rather had conceived, planned, and sanctioned them.

These twenty-two men, some of whom believed in a Prussian code of honor and in Christian principles of morality, were so blinded by racial and religious hatred, and so beguiled by military conquest that they forfeited their souls for a few years of illusory glory as the master race. Their crimes were so enormous that it was difficult to find words sufficiently scaled to describe them, so two recently coined words entered the English lexicon: holocaust and genocide .

These men are viewed todaythe ones who are rememberedas one-dimensional villains, but that is simplistic. A number of them held law degrees, which in Germany earned them the right to be addressed as Doctor. Many were cultured, enjoyed opera, and were knowledgeable of arts and literature. All had families, and some had mourned the loss of a spouse or grieved at the death of a child.

Although they were capable of the tenderest of human emotions, they could vouchsafe none to those who did not meet their Aryan ideals. What was lacking in their makeup that made this so will perhaps never be known and is outside the scope of this book.

The man who, more than any other person, made the trial come into fruition was Robert H. Jackson, associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, whom President Truman chose to be the Chief US prosecutor. Jackson fought for months not only against British reluctance to hold a trial, for it would be prodigal of time and resources, but French and Russian procrastination in finishing the development of their cases.

Besides having to solve myriad logistical problems, Mr. Justice Jackson had to traverse a legal minefield. From the time the idea of a trial was conceived, there were charges of ex post facto law, or making an act illegal after it had been committed, something prohibited by every system of jurisprudence. Although there were numerous treaties outlawing war, there were no specific international laws doing so, nor a procedure for trying any offenders. The Allies would have to make the case that these treaties, signed by dozens of countriesincluding Germany, had the force of law. They would try to advance international law rather than wait for it to catch up in a world that was rapidly becoming more dangerous.

Jacksons novel plan to try the defendants on conspiracy to wage aggressive war was not embraced by the other three AlliesGreat Britain, France, and the Soviet Union. Conspiracy was hard to prove in American law, harder in European law, and virtually impossible in international law. Mr. Justice Jackson however wanted to cast a wide net and pull in anyone in position of power who had aided the Nazi war machine, not just in the military, but in the areas of diplomacy, propaganda, finance, and governance.

The honor of making the opening statement of the trial went to Mr. Justice Jackson. As he walked toward the lectern, he surveyed the defendants in the dock; assembled there was more evil, he thought, than any place other than hell itself.

Conspicuous by his absence was the Fuhrer, Adolf Hitler, the person who, more than any other one man, had made the trial necessary. As the embodiment and exemplar of the Nazi ideal, he realized that he could not allow himself to be captured and put on trial like a common criminal. As his world collapsed around him, he and his wife of mere days, Eva Braun, committed suicide and had their bodies soaked with gasoline and burned in the courtyard of the Fuhrer Bunker, their home the last months of the war.

Although twenty-four men had been indicted, there were only twenty-one in the courtroom of the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg. Martin Bormann, Hitlers secretary and gatekeeper, had vanished into the chaos and rubble that had been Berlin. Some thought that he had escaped to South America to live under an alias, while others were convinced that he had been killed by the Russian shelling as that city collapsed. He would be tried in absentia.

Baron Gustav Krupp, of the famous Krupp Works, had been indicted, but it was discovered by medical examination just before the trial was to begin that he was physically and mentally incapable of aiding in his defense (he was bedridden, barely clinging to life) and that his son Alfried had run the company during the war. It was too late to indict him without delaying the trial; Alfried would have his day of reckoning in another venue, at another time.

The third empty chair belonged to Robert Ley, destroyer of labor unions and slave driver of the guest workers. He had committed suicide just days before the start of the trial.

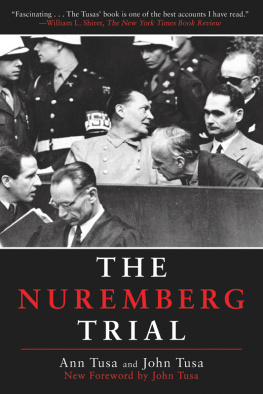

Twenty-one defendants looked at Mr. Justice Jackson as he laid his notes on the lectern. The biggest man, literally and figuratively, was Reichsmarshall Hermann Gring, the former number two man in the Nazi hierarchy. The once nineteen stone Gring had fallen off considerably on prison food and discipline, but still carried nearly two hundred pounds on his five-foot-six-inch frame; with his clothes hanging loosely off him, he looked fat and drawn at the same time. Having been weaned off drugs, his mind was clearer than it had been for years, and he would be a formidable adversary on the stand.

The mentally fragile Rudolf Hess had been Hitlers deputy fuhrer until his quixotic flight to Scotland in May of 1941. His mission, which sounded to him simple and logical, was to convince Great Britain to make peace; he would accomplish this through his friendship with the Duke of Hamilton, whom he had met at the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin. This friendship existed more in Hesss mind than in reality; and after landing, he was interned, spending the balance of the war in England, where he battled amnesia and other problems, real or imagined, before being delivered to Nuremberg. Looking into his eyes was like looking into the windows of a haunted house.

Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel was Hitlers ranking soldier. Tall, gray, and erect, he looked the part, but in reality was a mere toady, an empty suit. He issued no orders of any import that did not originate with Hitler.

General Alfred Jodl was Keitels subordinate and a thoroughly professional soldier. He would tell Hitler his strategic ideas and challenge himto a pointwhen he thought the Fuhrers ideas were likely to result in disaster.

Ernst Kaltenbrunner was, along with Himmler, in charge of the death camps after the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich. An ox of a man, nearly six feet six inches tall, with a bull neck and dangling simian arms, he had an angry-looking scar on his cheek, which he claimed was from a duel; more likely it was from an automobile accident.