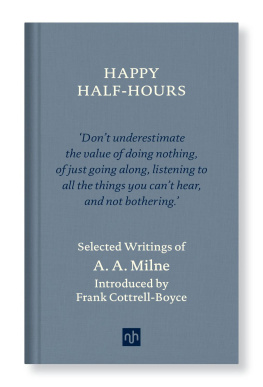

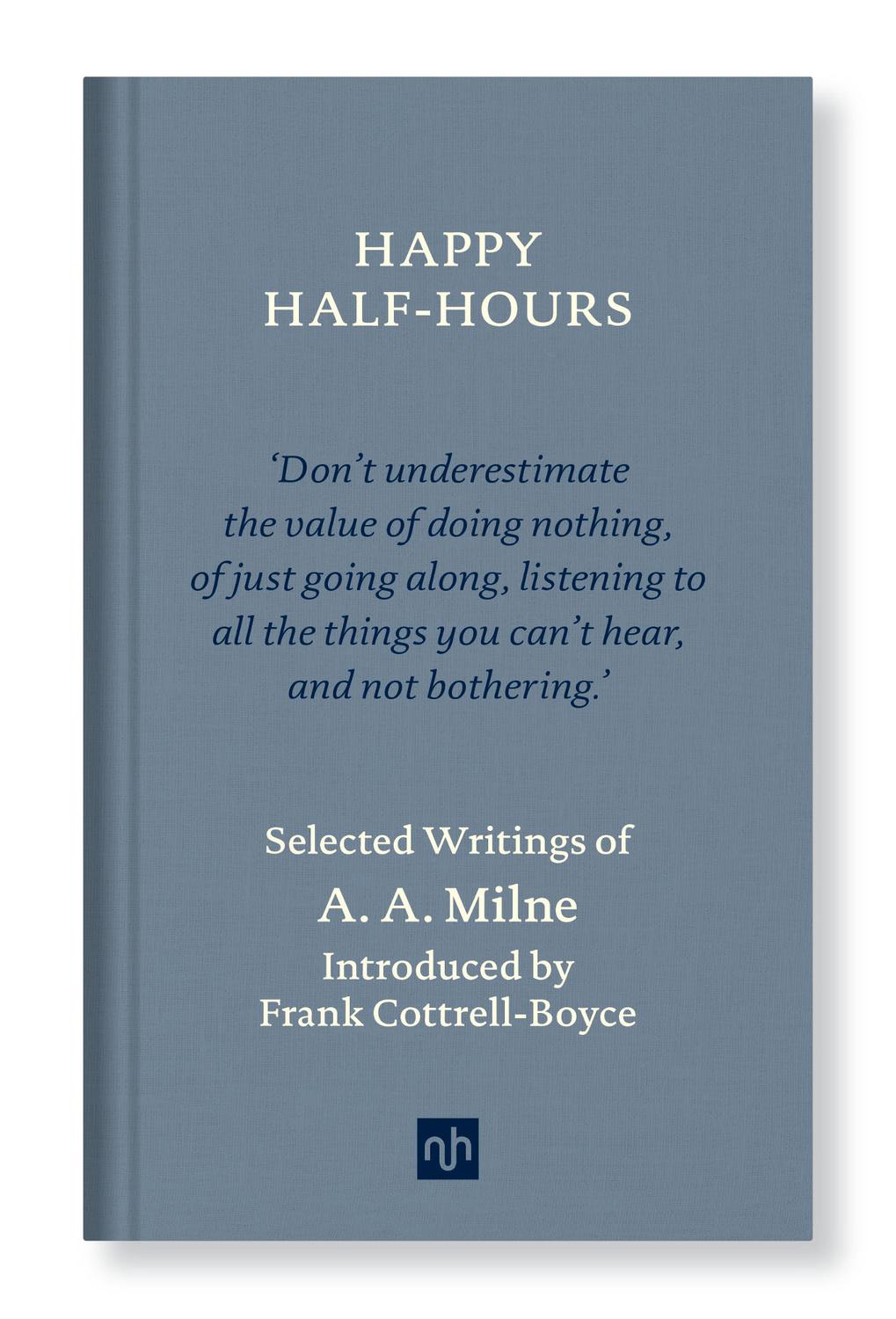

A. A. Milne - Happy Half-Hours

Here you can read online A. A. Milne - Happy Half-Hours full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: New York Review Books, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Happy Half-Hours

- Author:

- Publisher:New York Review Books

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Happy Half-Hours: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Happy Half-Hours" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Happy Half-Hours — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Happy Half-Hours" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Notting Hill Editions is an independent British publisher. The company was founded by Tom Kremer (19302017), champion of innovation and the man responsible for popularising the Rubiks Cube.

After a successful business career in toy invention Tom decided, at the age of eighty, to fulfil his passion for literature. In a fast-moving digital world Toms aim was to revive the art of the essay, and to create exceptionally beautiful books that would be lingered over and cherished.

Hailed as the shape of things to come, the family-run press brings to print the most surprising thinkers of past and present. In an era of information-overload, these collectible pocket-size books distil ideas that linger in the mind.

www.nottinghilleditions.com

- LITERARY LIFE

My Library - MARRIED LIFE

Wedding Bells - HOME LIFE

Fixtures and Fittings - PUBLIC LIFE

In London - MEDITATIVE LIFE

By the Sea - PEACEFUL LIFE

Men at Arms

xi Frank Cottrell-Boyce

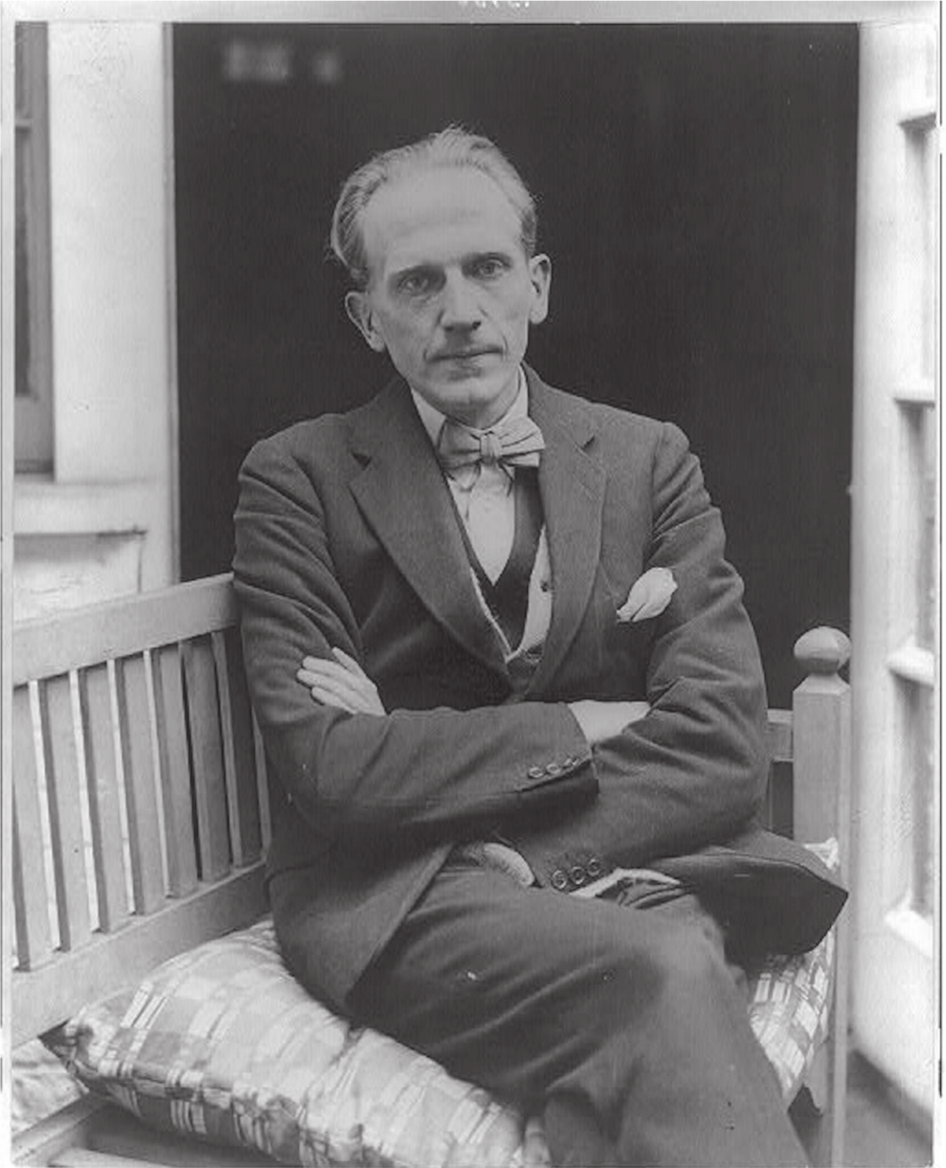

H ow does a nation pull itself together again after a disaster? How do we move on from overwhelming experiences? There was no doubt in A. A. Milnes mind that the First World War was a disaster. On the Somme, hed witnessed a lunacy that would shame the madhouse. One Austrian Archduke had been killed, he said, and this resulted directly in the death of ten million men who were not archdukes. Before the war he had been a star turn at Punch under the editorship of Owen Seaman. Seaman was a gloomy character who was partly the model for Eeyore. He was also an enthusiastic publisher and perpetrator of the kind of patriotic doggerel that cheered those ten million up the line to death. Milne was painfully aware of the part that culture played in soliciting sacrifice. Wars are fought for economic reasons, he wrote, but they are fought by volunteers for sentimental reasons. Seaman whipped up a lot of sentiment. Milne had been a pacifist since 1910. Seeing the Jingo-machine close up must have left a bitter taste. The pressure of it may have been partly why despite his pacifism he decided to sign up in 1915. Of course he didnt know then that this was only the first of the World Wars. He had every reason to believe that this was the War to End Wars xii a phrase that was coined by H. G. Wells, who sometimes played for the same cricket team as Milne. The Great War did not end all wars. But he learned that early on. In The Honour of Your Country he said that after the Somme all the talk in the Mess was of after-the-war. He goes on to describe a conversation with a colonel whose idea of Reconstruction included a large army of conscripts. The more Milne debates with him the more it becomes clear that nothing that happened on the Somme discredited the idea of war as a tool of diplomacy. The wittier Milnes responses become, the more obvious it is that war will continue to be part of the way we do things.

That cricket team he was in with Wells also included at various times J. M. Barrie, Kipling, Conan Doyle, P. G. Wodehouse, and G. K. Chesterton. It was Barrie who formed the team and named it the Allahakbarries, thinking he was playing with a phrase that meant God Help Us because he himself was such a bad player. So bad, in fact, that he banned the team from warming up at away grounds because the sight of them in action would only add to the oppositions confidence. In fact the phrase means God is Great as youll know from its appearance in various terrorist atrocities. The kind of violence Milne had witnessed does not go away.

In fact, Milnes after-the-war was a streak of enormous luck. Despite seeing active and highly dangerous service as a signals officer, his later posting on the xiii Isle of Wight somehow left him time to start writing plays. His first was for the children of his colonel. He wanted to give them something amusing at a time when life was not very amusing. Which is a decent enough mission for any writer. Certainly a better one than stirring up jingoistic sentiment (Milnes definition of a patriot was, someone who accuses other people of being unpatriotic). He moved away from Punch, ready to hit the West End running. As a successful playwright he would often earn 500 a week at a time when the average wage was about 4. Hed been lucky and he knew it. The American edition of his autobiography was actually called What Luck. The sense of being lucky gives the pieces he wrote about domestic life about sorting out his books or redecorating the bathroom the glow of unstated gratitude. He was lucky to have books to sort out. Lucky to be alive. Lucky to have got through the war without ever having to fire a shot in anger. Lucky therefore not to have had to compromise his pacificism.

Luck carries with it a sense of responsibility. Lucky survivors often feel theyve been saved for some great purpose, or at least that they should make the most of their opportunity. You can sense this in how hard Milne worked to give those pieces their hospitable ease. Nothing is harder than making things look easy. If you read On Writing for Children youll see he had no patience for any writer who was not bothering. Of a poem that was then a nursery favourite xiv John Gilpin he says there are sixty-three verses in it; it should have taken him a month of the hardest work within the capacity of man. When we read it, we know why it did not take him a month. He was a fierce and fearless critic. In one very funny piece he takes a Sherlock Holmes story to pieces to demonstrate that it cannot be put back together again because it was only held together with chewing gum and sellotape. I dont think Ive ever read a more insightful or bracing piece of criticism than his piece on Lewis Carroll and why the it was all a dream ending is such a betrayal. His friend Frank Swinnerton said that Milne combined a gift for persiflage with the sternness of a Covenanter, and it shows in the sheer work ethic he brought to the task of making it look like he was doing nothing.

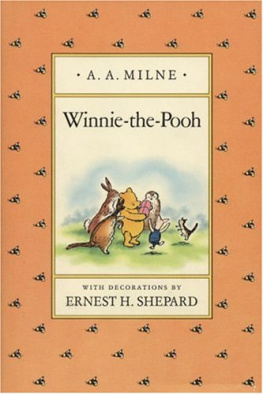

Of course no covenanter is going to be satisfied with merely being amusing. One of the most moving and tortured pieces in this collection is The End of a Chapter, his account of why he has to stop writing about Christopher Robin. Its part excuse-note, part examination of conscience. He admits that Christopher Robin only got his name because the Milnes wanted their son to be a great cricketer and great cricketers like W. G. Grace have initials rather than names. He jokes about writers jealousy of his own creation:

Imagine my amazement and disgust, then, when I discovered that in a night, so to speak, I had been pushed into a back place, and that the hero of When We Were Very Young was xv not, as I had modestly expected, the author, but a curiously-named child of whom, at this time, I had scarcely heard. It was this Christopher Robin who kept mice, walked on the lines and not in the squares, and wondered what to do on a spring morning; it was this Christopher Robin, not I, whom Americans were clamouring to see; and, in fact (to make due acknowledgement at last), it was this Christopher Robin, not I, not the publishers, who was selling the book in such large and ridiculous quantities.

Overwhelming success is harder to deal with than failure. At least failure has an element of hope in it. Success asserts a huge gravitational pull from which its almost impossible to achieve escape velocity. Look how Conan Doyle struggled with Sherlock Holmes. How Steve Coogan keeps going back to Alan Partridge. How J. K. Rowling keeps returning to the Potter universe. Milne never returned. His refusal to dilute the legacy is partly why the colours of the Hundred Acre Wood are so fresh. He walked out of the trees, up to Galleons Leap, and out into the World. Then he tried to stop a war.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Happy Half-Hours»

Look at similar books to Happy Half-Hours. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Happy Half-Hours and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.