Table of Contents

Praise forCod

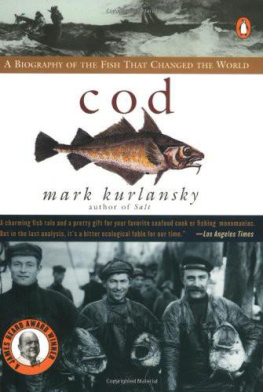

A subject as mighty and tragic as this deserves an excellent biographer, and in Mark Kurlansky, cod has found one. Beautifully written and elegantly illustrated ... Kurlanskys marvelous fish opus stands as a reminder of what good non-fiction used to be: eloquent, learned, and full of earthy narratives that delight and appall.

Toronto Globe and Mail

In the end the book stands as a kind of elegy, a loving eulogy not only to a fish, but to the people whose lives have been shaped by the habits of the fish, and whose way of life is now at an end.

Newsday

What a prodigious creature is the cod. Kurlanskys approach is intriguingand deceptively whimsical. This little book is a work of no small consequence.

Business Week

An elegant brief history ... related with vast brio and wit.

Los Angeles Times

In the story of the cod, Mark Kurlansky has found the tragic fable of our ageabundance turned to scarcity through determined shortsightedness. This classic history will stand as an epitaph and a warning.

Bill McKibben

This eminently readable book is a new tool for scanning world history.

The New York Times Book Review

In this fascinating story of cod, written in a flowing, poetic prose, the author takes you back to the ancient Basque fisherman and the recipes of the fourteenth-century Taillevent, the eighteenth-century Hannah Glasse, and the nineteenth-century Alexandre Dumas. This exceptional book entertainingly reveals the importance of this wonderful fish in history.

Jacques Pepin

One emerges from Mark Kurlanskys little book with a feeling that the codfish not only changed the world during the past one thousand years but seemed to define it.

Ocean Navigator

A readable, credible, and at times incredible tale.

Saveur

One helluva fish.

Entertainment Weekly

PENGUIN BOOKS

COD

Mark Kurlansky worked for several years on commercial fishing boats, and subsequently became a journalist, covering beats in Eastern and Western Europe, the Caribbean, and Latin America for the Chicago Tribune and the International Herald Tribune. He has written for magazines including Harpers, Audubon, and The New York Times Magazine, and contributes a column on food history to Food & Wine magazine. In addition to Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World, he is the author of A Continent of Islands: Searching for the Caribbean Destiny, A Chosen Few: The Resurrection of European Jewry, The Basque History of the World, and Salt. He lives in New York City.

THE QUESTION OF QUESTIONS FOR MANKINDTHE PROBLEM WHICH UNDERLIES ALL OTHERS, AND IS MORE DEEPLY INTERESTING THAN ANY OTHERIS THE ASCER- TAINMENT OF THE PLACE WHICH MAN OCCUPIES IN NATURE AND OF HIS RELATIONS TO THE UNIVERSE OF THINGS.

H. Thomas Henry Huxley,

Mans Place in Nature

SO THE FIRST BIOLOGICAL LESSON OF HISTORY IS THAT LIFE IS COMPETITION. COMPETITION IS NOT ONLY THE LIFE OF TRADE, IT IS THE TRADE OF LIFEPEACEFUL WHEN FOOD ABOUNDS, VIOLENT WHEN THE MOUTHS OUTRUN THE FOOD. ANIMALS EAT ONE ANOTHER WITHOUT QUALM; CIVILIZED MEN CONSUME ONE ANOTHER BY DUE PROCESS OF LAW.

Will and Ariel Durant,

The Lessons of History

Prologue: Sentry on the Headlands (So Close to Ireland)

THE HERRING ARE NOT IN THE TIDES AS THEY WERE OF OLD;

MY SORROW FOR MANY A CREAK GAVE THE CREEL IN THE CART

THAT CARRIED THE TAKE TO SLIGO TOWN TO BE SOLD, WHEN I WAS A BOY WITH NEVER A CRACK IN MY HEART.

William Butler Yeats, The Meditation of the Old Fisherman

These are the fishermen who stand sentry over the cod stocks off the headlands of North America, the fishermen who went to sea but forgot their pencil.

Sam Lee, dressed in black rubber boots and a red flotation jacket made even brighter by its newness, drives his late-model pickup truck through the last murk of night, down to the wharves that stretch out to where the water is deep enough for a shallow fishing skiff. The warehouses, meeting halls, and tackle shops are all built out above the shallow water on stilts. This has freed up the narrow strip of flat land where the steep little mountains stop just before the waters edge. The level area had once been needed to spread out thousands of splayed and salted cod for drying in the open air.

The salting had stopped almost thirty years before, but Petty Harbour still looks like a crowded little port, its few commercial buildings crunched in along the water, while houses scatter up onto the beginnings of the slopes.

At the wharves, Sam meets up with Leonard Stack and Bernard Chafe carrying flashlights and joking about Sams new jacket, shielding their eyes from its shocking brilliance. Grumbling about fishery politics, about last nights television talk of reopening groundfishing to the public on a limited basis, they climb down into Leonards thirty-two-foot, open-decked trap skiff.

Asked if he could really float with that jacket, Sam answers, I dont want to find out! And that is all they say about the black water a few feet away on either side of them as the boat heads out in the first violet light of early-autumn morning. Cod like the water this time of year because they think it is warm. But forty-five degrees Fahrenheit is a cods idea of warm, and the gunwales around the edge of a trap skiff are only inches high. This same day, in another community, the bodies of two fishermen who fell overboard are found. This isnt something fishermen talk about.

They head out to sea. Sam, a small, dark-haired man, with a touch of rose on his clean-shaven cheeks, is stuffed into his scarlet flotation jacket. Leonard is in the little pilothouse, while Bernard, in his flame orange overalls, stands with Sam on the open deck looking contemplatively at a flat sea of dark, polished facets. The light is beginning to warm a clear sky. Once the sun is up, the only clouds are cotton candy fog stuck between the rocky, still-green hills of the September coastline.

They find their fishing grounds by land markings. When a brown rock is aligned over the church steeple, when certain houses first come into view, or when they first sight the white spot on a rock that they call the Madame because in their imagination it looks like a skirt and a bonnet, they are ready to drop anchor and begin fishing.

Only today, having forgotten a pencil, they head over to the other boat where the three-man crew is already hauling cod with handlines. After a few jokes about the size of this sorry young catch, someone tosses over a pencil. They are ready to fish.

These men are part of the Sentinel Fishery, now the only legal cod fishery in Newfoundland. In July 1992, the Canadian government closed Newfoundland waters, the Grand Banks, and most of the Gulf of St. Lawrence to groundfishing. Groundfish, of which the most sought after is cod, are those that live in the bottom layer of the oceans water. By the time the moratorium was announced, the fishermen of Petty Harbour, seeing the rapid decline of their once prolific catch, had been demanding it for years. They had claimed, and it is now acknowledged, that the offshore trawlers were taking nearly every last cod. In the 1980s, government scientists had ignored the cry of inshore fishermen that the cod were disappearing. This deafness proved costly.