Table of Contents

ALSO BY MARK KURLANSKY

NONFICTION

The Food of a Younger Land: A Portrait of American FoodBefore the National Highway System, Before Chain Restaurants, and Before Frozen Food, When the Nations Food Was Seasonal, Regional, and Traditionalfrom the Lost WPA Files

The Last Fish Tale: The Fate of the Atlantic and Survival in Gloucester, Americas Oldest Fishing Port and Most Original Town

The Big Oyster: History on the Half-Shell

Nonviolence: The History of a Dangerous Idea

1968: The Year That Rocked the World

Salt: A World History

The Basque History of the World

Cod: A Biography of the Fish That Changed the World

A Chosen Few: The Resurrection of European Jewry

A Continent of Islands: Searching for the Caribbean Destiny

ANTHOLOGY

Choice Cuts:

A Savory Selection of Food Writing

from Around the World and Throughout History

FICTION

Boogaloo on 2nd Avenue: A Novel of Pastry, Guilt, and Music

The White Man in the Tree and Other Stories

FOR CHILDREN

The Cods Tale

The Girl Who Swam to Euskadi

The Story of Salt

TRANSLATION

The Belly of Paris, by mile Zola

A MIS VIEJOS AMIGOS EL PUEBLO DOMINIC ANO, EN LA ESPERANZA QUE UN DA ENCUENTRE LA JUSTICIA Y PROSPERIDAD QUE USTED SE MERECE

AND FOR TALIA FEIGA, WHOSE GREAT HEART IS BIG AS A MOUNTAIN

(Tanto arrojo en la lucha irremediable

Y an no hay quien lo sepa!

Tanto acero y fulgor de resistir

Y an no hay quien lo vea!)

(So much daring in the unresolvable struggle

Even though there is no one who knows it!

So much steel and flashing in resistance

Even though there is no one who sees it!)

Pedro Mir, Si Alguien Quiere Saber Cul Es Mi Patria If Someone Wants to Know Which Country Is Mine

PROLOGUE

Gracias, Presidente

This is a book about what is known in America as making it. And like all such tales, it is also a story about not making it. In this Dominican town, San Pedro de Macors, the difference between making it and not making it is usually baseball.

If you do not make it, there is sugarcanebut only for half the year. Sometime between Christmas and the Dominican national holiday on February 27, depending on how rainy the summer was, the pendoneswhite feathery shootsappear above the rippling green cane fields of San Pedro de Macors. In the English-speaking islands of the Caribbean, where many of the families of San Pedros sugar workers originated, the field is said to be in arrow because the pendones point upward. It means that the sugarcane is ripe for cutting and the cane harvest, the zafra, can begin.

It is an exciting moment, because most people who work in sugar here have employment only during the four to six months of the zafra. In an election year, such as 2008, at the beginning of the harvest a sign goes up at the Porvenir sugar mill, which is controlled by the ruling party. It says, Gracias, Presidente, por una nueva zafra, Thank you, President, for a new cane harvest, as though he, Leonel Fernndez, the New York-educated caudillorunning again as he had in 2004 and in 1996, which was the last time Dominicans believed he offered anything new, his face on posters everywhere with the smile of an encyclopedia salesmanhad personally caused the sugarcane to grow.

Some of the San Pedro millsSanta Fe, Angelina, Puerto Rico, and Las Pajasno longer operate. Four working mills remain, though not at full capacity: Quisqueya, Consuelo, Cristbal Coln, and Porvenir. When the zafra is on, red glows can be seen from San Pedro along the northern horizon where the mill fires burn all night, cooking down cane juice. Porvenir, which in Spanish means future, was originally on the edge of the city like the others, but the town grew around it and now trucks full of grape-red sticks of cane must drive through the traffic-clogged center of town to deliver to the mill.

Street kids, the ones who survive by shining shoes or washing the windshields of the cars that stop at traffic lights, run behind the trucks and pull off canes to suck. Sometimes they hold a stick of cane in a batters stance. On the street, San Pedro boys regularly coil into a batters stance anyway. Having a stick in hand, some cant resist taking a practice swing with a small rocka dangerous habit in the crowded parts of town. But if they were to make a mistake and hit a rich mans shiny large SUV, chances are the wealthy driver hiding behind the smoked glass would be a baseball player who not that many years before had himself been whacking around stones with a stalk of sugarcane.

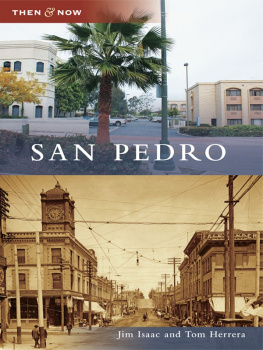

The road out of town that leads to the other mills begins at the green, white, and ocher Estadio Tetelo Vargas, home of the Estrellas Orientales, the Eastern Stars. San Pedros long-suffering and always promising baseball team, founded in 1910, is older than many of the major-league clubs in America. With a center-field wall at 385 feet, Tetelo Vargas is a major-league-size field, though with fewer seats, more like a Triple A stadium. Behind the outfield wall, the drooping fronds of tall palms can be seen, and in the distance, sticking up behind right field, the smokestack of Porvenir.

The road alongside the stadium goes straight northa rutted pockmarked remnant of the once paved two-lane route that has hosted too many trucks, which now dangerously zigzag around potholes. The road leads through the rural zone that is still San Pedro to whole villages that have grown up around the mills after which they were named: Angelina, Consuelo, Santa Fe... Soonstill in San Pedrothe road seems like a causeway over a vast vegetable sea with lapping silver and green waves of sugarcane. Some already-cleared fields look as if they had gotten bad haircuts. Leggy white birds called galsas graze there until sunset, when they nest in the trees at the fields edges.

At lunchtime the galsas were still in the fields and the cane cutters in Consuelo were under the trees, resting in the shade from a broiling midday sun. Cutting cane is the worst job in the Dominican Republic, the hardest work for the least pay. It has always been said that no Dominican would ever do such worknever even want to be seen doing it. Desperate people from other sugar-producing islands with dying sugar industries were brought in to cut the cane. And so places like Consuelo have a polyglot culture with West Indian English and Haitian Creole as commonly spoken as Spanish and often mixed in the same sentence.

But that was in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when the Dominican Republic was an underpopulated country with a booming sugar industry. Today it is the reverse, and the job market is becoming desperate. In this field the resting cane cutters were born Dominican.