BLOOMSBURY CHILDRENS BOOKS

Bloomsbury Publishing Inc., part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018

This electronic edition published in 2019 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY CHILDRENS BOOKS, and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in the United States of America in November 2019 by Bloomsbury Childrens Books

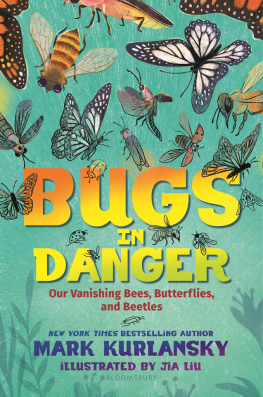

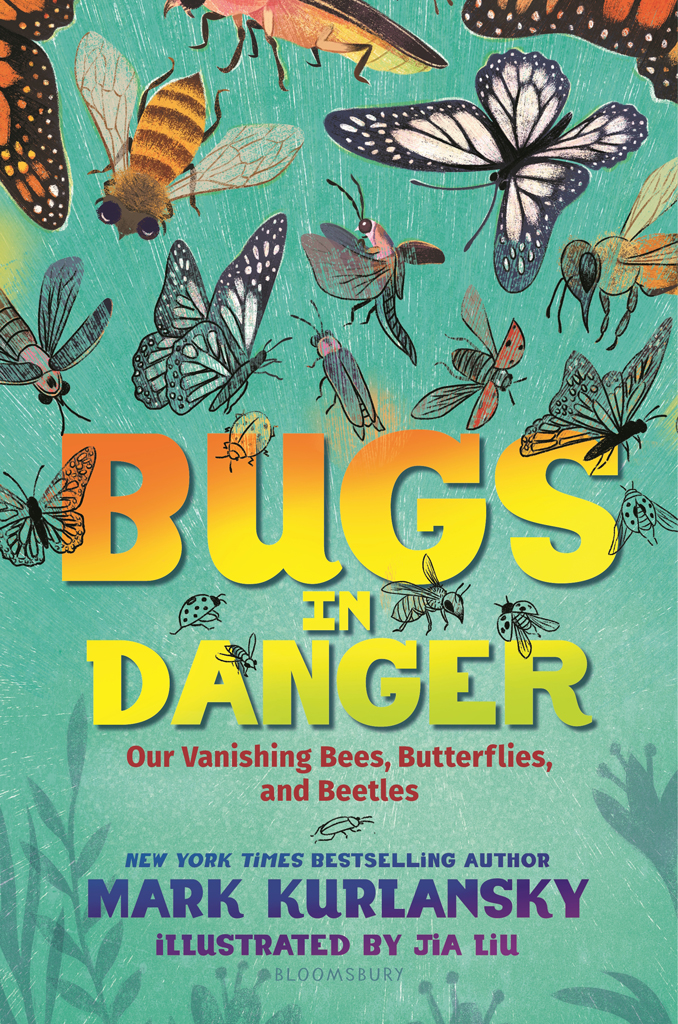

Text copyright 2019 by Mark Kurlansky

Illustrations copyright 2019 by Jia Liu

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Bloomsbury books may be purchased for business or promotional use. For information on bulk purchases please contact Macmillan Corporate and Premium Sales Department at

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kurlansky, Mark, author. | Liu, Jia (Illustrator), illustrator.

Title: Bugs in danger : our vanishing bees, butterflies, and beetles / by Mark Kurlansky ; illustrated by Jia Liu.

Description: New York : Bloomsbury, 2019.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019019148 (print) | LCCN 2019022300 (e-book)

ISBN: 978-1-5476-0085-4 (HB)

ISBN: 978-1-5476-0499-9 (PB)

ISBN: 978-1-5476-0340-4 (eBook)

Subjects: LCSH: InsectsConservationJuvenile literature. | Endangered speciesJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC QL467.2.K87 2019 (print) | LCC QL467.2 (e-book) | DDC 595.7dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019019148

LC e-book record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019022300

Book design by John Candell

To find out more about our authors and their books please visit www.bloomsbury.com where you will find extracts, author interviews and details of forthcoming events, and to be the first to hear about latest releases and special offers, sign up for our newsletters.

To Charles Darwin and the teachers who pass on his knowledge

All these sounds, the crowing of cocks, the baying of dogs, and the hum of insects at noon, are the evidence of natures health or sound state.

Henry David Thoreau,

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, 1849

contEnts

fly swattErs

HOW OFTEN DO YOU step on an ant, swat a fly, or slap at a mosquito? On a buggy afternoon, when youre swatting away flies, mosquitoes, and other little beasts, who could blame you for thinking how much better life would be with fewer bugs? To swat an insect is a natural instinct. It is the way we are designed, and it is what is supposed to happen.

Often there are good reasons to get rid of bugsthey bite, they sting, they carry diseases, they destroy crops, and they even eat up houses. But insects are disappearing from the planet at an alarming rate. The intermingling of a huge number of species is essential for the survival of all animals, including humans. When animals start disappearing, it is a threat to the survival of all of us.

Each life on Earth contributes to other lives on Earth. Sometimes that might just mean another form of life to keep that population in check. So, without ladybugs, there would be too many aphids. These bugs would then devour too many crops, and then we would not have those plants to eat. Life is an enormous interconnected web, and every species adds something. We need them all.

To some, insects are just creepy-crawly things. It is understandable not to like termites, which eat wood and destroy your house, but some people dont even like ants. I had a question for E. O. Wilson, who is an evolutionary biologist and a prominent authority on ants: what should you do when ants enter your home? He said that there was no cause for concern, because they are merely passing through: just allow them some time, and they will usually be gone. (Though, in the meantime, he pointed out that they are particularly fond of tuna fish and whipped cream. But, of course, if you were to make life too nice for them, like some house-guests, they might decide to stay.)

The truth is, though, we are getting fewer bug visitors at home. Thats a crisis, because we actually need them there. And we need them in woods and fields and everywhere on Earth.

Insects are part of our landscape. The buzzing in the woods or in a garden tells us nature is alive and well. In tropical rain forests, there are so many insects that it is more than a buzzalmost a roar.

In truth, people tend to like some insects more than others. Tourists gather where fireflies sparkle and where butterflies nest. We will stop our day to watch a bee hovering over a bright and nectar-rich flower or to watch butterflies flickering through a field. We appreciate bees for making us delicious honey. As a child, I spent endless lazy summer hours watching bright two-spotted ladybugs scampering over the birch tree in my familys New England backyard. Butterflies, ladybugs, fireflies, and bees are some of our most beloved insectsand each of these is on the list of vanishing insects. Even if we give little thought to all these small, strange creatures, we are not prepared to live without them.

I am set to light the ground,

While the beetle goes his round:

Follow now the beetles hum;

Little wanderer hie thee home.

William Blake

how bugs fit in

IF WE CARE ABOUT the health of our planet, we cant choose which animals lives we want to save; we have to care about them all. However, the closer a species is to us humans, the more we seem to care about it.

Nature did not arrange itself into neat separate groups. That was our doing, starting with one man from eighteenth-century Sweden. Carl Linnaeus created a system to organize, name, and classify all living organisms. He identified about 13,000 species, and he expected to eventually classify all of them. He divided living things into categories, ranging from the most general grouping to the most specific: kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, species. You can remember these groups by using the phrase Kangaroos Play Cellos, Orangutans Fiddle, Gorillas Sing, or King, Please Come Out, For Goodness Sake, if you prefer.