CONTENTS

1 BUZZ FREE: A WORLD WITHOUT BEES

Stuck Under a Truck in the Atacama Desert, Chile

2 THE FUTURE OF OUR FOOD

Serenading the Bees on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia

3 HONEY, QUEENS, HARD-WORKING WORKERS AND STINGS: MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT BEES

Stung by Bee Killers on the Isle of Wight, United Kingdom

4 A BEE OR NOT A BEE? A DIFFICULT QUESTION TO ANSWER

Insulting the Experts in Portal, Arizona

5 TWO BEES OR NOT TWO BEES? AN EVEN MORE DIFFICULT QUESTION TO ANSWER

Uncovering Irregularities at the National History Museum, London

6 ITS A BEES LIFE

Up Before Dawn in the Australian Outback

7 THE SOCIABLE BEE

Digging Nests After Dark in Calgary, Alberta

8 SEX AND DEATH IN BEES

Choosing a Mate in Subtropical Florida

9 WHERE THE BEE SUCKS, THERE HUNT I

Painful Bee Sampling in the Tehuacan Desert, Mexico

10 ANTI-BEES

Sexually Transmitted Child-Eating Female Impersonators on a California Sand Dune

11 WHAT ARE WE DOING TO THE BEES?

Bee-Free Day in Germany

12 THE PROVERBIAL CANARIES IN THE COAL MINE

Upsetting Ornithologists in Rome

13 HELP THE BEES

Dodging Hippos at the African Pollinator Summit

EPILOGUE

Bee Worship on the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico

1

Buzz Free: A World Without Bees

STUCK UNDER A TRUCK IN THE ATACAMA DESERT, CHILE

I t was three in the afternoon and over 30C, yet despite the heat there was not a drop of sweat on my body. The air was so dry that any perspiration was sucked from my pores before I even felt it. I could see for miles in all directions, but there was no sign of human habitation. I hadnt seen a soul for hours. The entire vista was in two coloursthe ground was beige and the sky blueand even the Andes Mountains, faintly visible on the horizon, looked blue from this distance. I had been stuck here in the Atacama Desert in northern Chile for three hours, trying to dig the back wheels of a half-ton truck out of the sand.

The day had begun well. I had found a tiny trickle of water emerging from an embankment at the side of a dirt road; there was some vegetation growing around the moisture, and some bees were visiting the flowers. I collected a few of them and then drove off towards my next sample site. Two hours of driving and three hours of digging later, and I had not seen a single living thingno other drivers, not an insect, not a plant.

The Atacama Desert is both the driest and the oldest desert in the world. People claim that there are parts of this desert where rain has never fallen, although geologists have told me that it must have rained at least once in the past hundred years over most of this enormous stretch of barren land. There are indications of past precipitation on the surfaces of the mine tailings, extrusions from the nitrate mines that dotted the landscape with human activity a century ago. This is an eerie place to travel, as in some areas the only signs of past human habitation are the graveyards that house the dead. The mausoleums shelter the desiccated remains of the mine managers and their families (the miners themselves were given less prestigious burials). Apart from some vandalism, the coffins and their contents are exactly as they were in the early years of the twentieth century. Where it (almost) never rains, the dead become mummified.

Imagine living in a place where it rains perhaps once every hundred years. Not surprisingly, detailed weather data are not available for most of this large, sparsely populated area, but there are meteorological records that extend back for long periods for several places. The northernmost city in Chile is Arica; the average rainfall there between 1987 and 2002 was three millimetres per year. But that average is misleading because over one-third of the total rainfall in that sixteen-year period fell on a single day. It rained on a total of just fourteen days in those sixteen years, and in an earlier period, not a single drop of rain was recorded for fourteen years in a row. It seemed that the place where I was now stuck was drier than Arica, and I had only my broken-down truck to keep me company as the hours passed by.

This was not the first time I had got into a bit of a pickle while doing fieldwork. For my Ph.D. at the University of Toronto I had studied geographic variation in bee social behaviour, obtaining samples all the way from cold temperate Ontario to the subtropical climes of the Florida Keys. At one point I drove my car into the Okefenokee Swamp at dawn trying to get to the next sampling site in time.

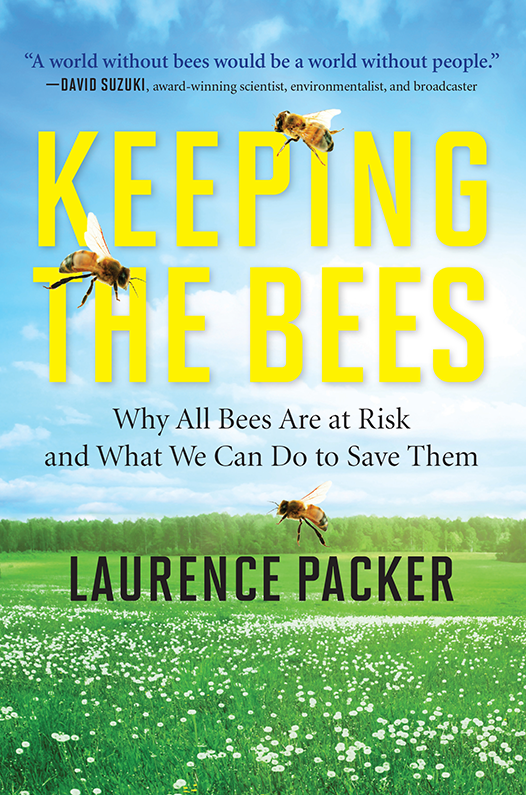

Since then I have authored or co-authored over one hundred research articles on bees, most of them since becoming a professor of biology at York University in Toronto, Canada. Over the past thirty-five years I have travelled to all continents except Antarctica (where there are no bees) because of my fascination with these essential and beautiful little insects. Arid lands are my preferred destinations for the simple reason that bee diversity is higher in semi-deserts than in any other type of habitat. The normally dry and sunny weather is appealing to bees, which dont like to fly when it is raining or cloudy. Although my earliest research was mostly on bee behaviour, I have become increasingly aware of the need to promote the conservation of bees. Research performed in my laboratory demonstrates that bees are at a much higher risk of extinction than most other organisms. And thats a concern because the world as we know it would not exist without the pollination activities of bees: not only would there be few wildflowers, but our food supply would be substantially reduced. Some almost essential itemssuch as coffeewould be at risk (though many would consider coffee absolutely essential). So it is extremely important to increase our understanding of bees and to spread the word about these valuable creatures as widely as possible.

Consequently, I now put considerable effort into increasing general awareness of the significance of bees. I have, for example, written a pamphlet on the bees of Toronto; taught bee-identification courses in Ontario, Arizona and Kenya; written identification guides to the bees of Canada and adapted previously published ones for the needs of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

It is because of my interest in the conservation of bees that I was in the middle of the Atacama Desert with no shade but that underneath the truck, where I had spent quite some time. Fortunately, I had a large drum of wateressential for anyone travelling in this part of the worldand a drum of gasoline. I knew of other entomologists who had run out of gas and been stranded in this region for days before anyone else passed by. Without water and gas, you would not last long. I imagined the headline: Mummified Bee Biologist Found in Desert.

Large amounts of water and gas are two things everyone needs in this beautiful wilderness. But few take a drum of liquid nitrogen with them as well. Why would I take liquid nitrogen into the desert? At -196C, it was certainly not for cooling beer. The liquid nitrogen was for storing bees in a way that prevented their proteins from breaking down. Why was I interested in the proteins of desert bees? Why was I risking life and limb studying the proteins of insects so inconspicuous that even if you had thousands of them nesting in your lawn you would probably not know it? The answers to these questions form part of an extended narrative that eventually led me to conclude that bees may be the proverbial canaries in the coal mine of the globes terrestrial habitats. Not only do I believe that bees can tell us much about the state of the natural world, but I also believe they are particularly good at indicating the state of the environment in areas that have been considerably influenced by human activity. But in case you think bees are unimportant, or even perhaps mostly a nuisance (after all, some of them sting), lets imagine what the world would be like without them.