To the bees, with thanks for all you do R.H.

Copyright 2020 by Rebecca E. Hirsch

All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.

Twenty-First Century Books

An imprint of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc.

241 First Avenue North

Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA

For reading levels and more information, look up this title at www.lernerbooks.com .

Main body text set in ITC Caslon 224 Std Book.

Typeface provided by Adobe Systems.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hirsch, Rebecca E., author.

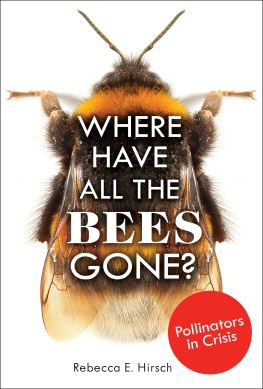

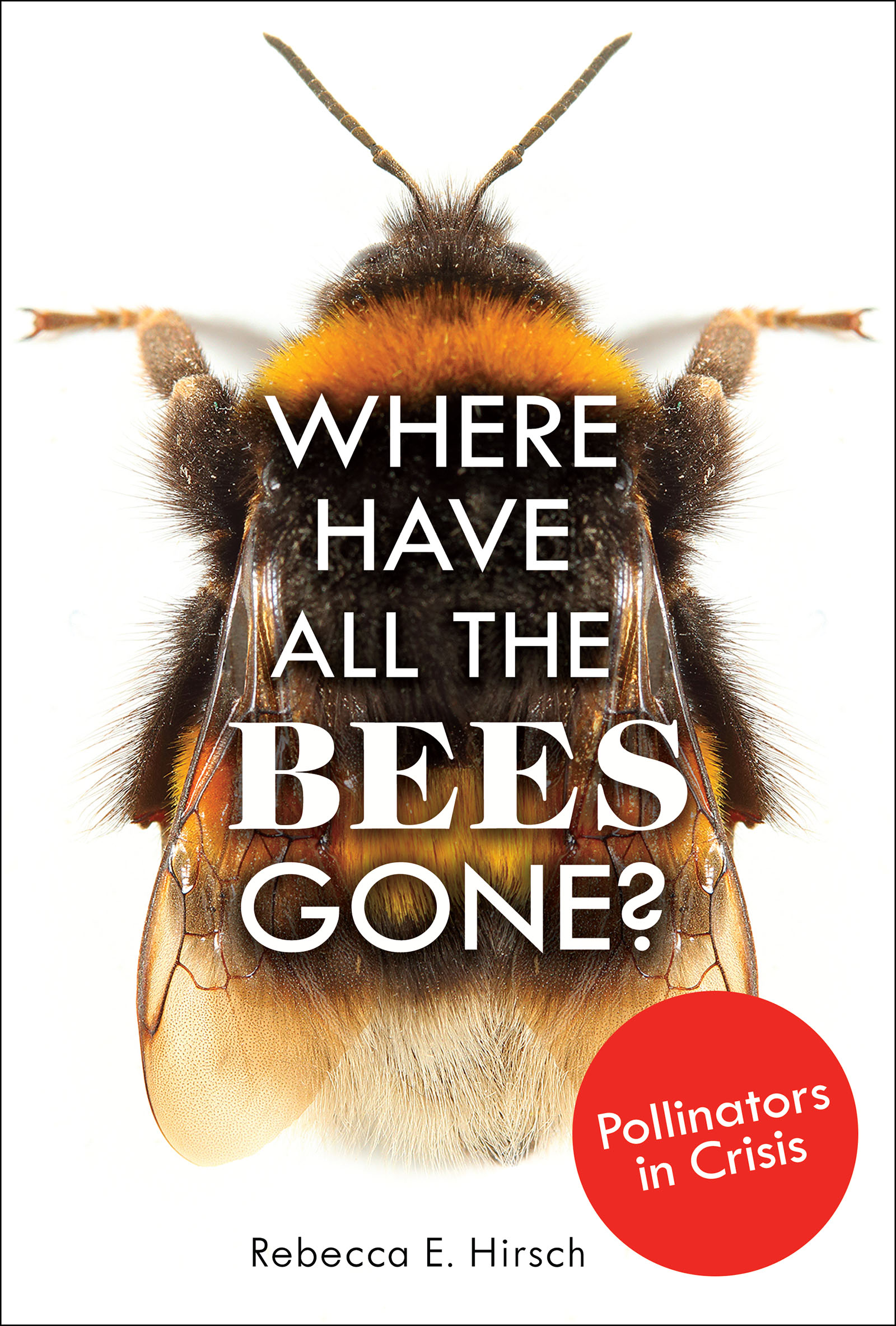

Title: Where have all the bees gone? : pollinators in crisis / by Rebecca E. Hirsch.

Description: Minneapolis : Twenty-First Century Books, [2020] | Audience: Age 1318. | Audience: Grade 9 to 12. | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2019020684 (print) | LCCN 2019021603 (ebook) | ISBN 9781541583856 (eb pdf) | ISBN 9781541534636 (lb : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: BeesConservationJuvenile literature. | Insect pollinatorsConservationJuvenile literature. | Pollination by beesJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC QL568.A6 (ebook) | LCC QL568.A6 H485 2020 (print) | DDC 595.79/9dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019020684

Manufactured in the United States of America

1-44880-35729-8/7/2019

Contents

The Last Franklins Bumblebee

An Ancient Relationship

Pollination Powerhouses

A Bee Cs

Disease Spillover

The Day the Bees Died

Bee Town, USA

Whats Best for Bees?

The Last Franklins Bumblebee

People often ask the value of Franklins bumblebee. In terms of a direct contribution to the grand scale of human economies, perhaps not much, but no one has measured its contribution in those terms. However, in the grand scheme of our planet and its environmental values, I would say it is priceless.

Robbin Thorp, entomologist

Robbin Thorp, wearing a bright yellow T-shirt with a bumblebee printed across the front, drives his white truck along a road on Mount Ashland in southern Oregon. He steers past the base of a ski lift and rolls to a stop beside an alpine meadow. He cuts the engine and steps out into the sunshine.

Under a sky of blue streaked white with clouds, the meadow blazes with pink and yellow flowers. But Thorp focuses on something other than the fine weather and quiet scenery. He is on a quest.

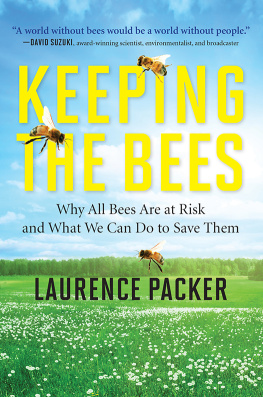

Thorp is a retired entomologist (a scientist who studies insects). He is searching for the bee pictured on his shirt: Franklins bumblebee. It looks much like any other of North Americas forty-six species of bumblebeebig, fat, and fuzzy. Unlike other bumblebees, it has a round, black face and a U-shaped marking on its back, right between the wings.

As far as bumblebees go, Franklins isnt remarkable, except for one thing: it has gone missing. Once common in alpine meadows like this one, the bee seems to have vanished. Thorp hasnt seen one in ten years.

Slowly, Thorp walks from flower to flower, shoes crunching on the craggy ground. In one hand, he holds a white net and in the other, a device like a squirt gun. But this device doesnt shoot water. It slurps bees.

As he walks, he peers at each clump of flowers and inspects the bees that are busily looking for food there. When he sees a bee that deserves a closer look, he pauses, leans forward, raises the bee vacuum, and takes aim.

ZEEEEEOOOP!

He studies the imprisoned creature through a magnifying lens built into the vacuum. He looks for the telltale markings. Is it that beethe one on his shirt? The one he seeks? Is it a Franklins?

Again and again, with each bee he finds, the answer is no. What has happened to Franklins bumblebee?

A bee flies through a meadow, looking for the nectar it needs to survive.

Disappearing Bees

The story of the disappearance of Franklins bumblebee begins in the 1990s. Thats when US Forest Service officials approached Thorp, who was then a professor at the University of CaliforniaDavis, and asked him to monitor the species. At the time, Bombus franklini (the bees scientific name) had the smallest geographic range of any of the worlds 250 species of bumblebees. The rare bee lived only in southern Oregon and Northern California, between the Cascade Range and the Pacific Ocean. Its entire range could fit inside an oval just 200 miles (322 km) north to south and 70 miles (113 km) east to west.

Whats in a Name?

All plants and animals have common names, such as the Shasta daisy and the peregrine falcon. Biologists also use a scientific naming system created by Swedish scientist Carolus Linnaeus in the mid-eighteenth century. The system uses Latin-based terms to identify each plant or animals genus (group) and species (specific kind within that group). For example, all bumblebees belong to the same genus, Bombus , so all share that first name. Each species within Bombus has a distinct second name. Franklins bumblebee is called Bombus franklini , while the western bumblebee is Bombus occidentalis .

Genus and species are the most precise classifications for living things. But these categories fall under a larger naming umbrella of eight levels: domain, kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. You can see the hierarchy by looking at Franklins bumblebee. It belongs to the domain Eukarya, a group that includes all plants and animals. Within that category, Franklins bumblebee belongs to the kingdom Animalia (the animal kingdom), the phylum Arthropoda (animals with jointed legs and no backbones), the class Insecta (insects), the order Hymenoptera (a group of insects including ants, wasps, and bees), the family Apidae (bees), and the genus Bombus (bumblebees). The species name Bombus franklini is the designation for Franklins bumblebee. Each kind of living thing has its own species name, and members of the same species can mate with one another.

Because the chubby bee with the round black face and the U on its back was so rare, Forest Service officials wondered whether it should be listed as endangered. An endangered species is one at risk of going extinct, or completely disappearing from Earth.

The US Endangered Species Act of 1973 protects animals and plants in the United States that are in danger of becoming extinct. When the US government adds a species to the endangered species list, federal agencies must conserve and protect the species and its habitatthe environment in which the plant or animal normally lives. Agencies must prohibit actions that would harm the species, such as hunting it or destroying forests. The act has saved several animals from extinction. The bald eagle, peregrine falcon, brown pelican, and American alligator all came dangerously close to extinction but rebounded with protection from the Endangered Species Act. Was Franklins bumblebee a good candidate for protection?