This book is dedicated to everyone who tears up their front yard to plant big chaotic wildflower gardens, to farmers who think hedgerows and wildflower field borders are just as important as crops, to urban planners and landscapers who turn gray and lifeless concrete landscapes into corridors of biodiversity, and to members of the Xerces Society.

Contents

Whats Old Is New

Dr. Edith Patch was the original insect conservationist, one of the first critics of indiscriminate pesticide use, an author of fantastically interesting childrens books, and an early pioneer for women in science. But it was in her role as the first female president of the Entomological Society of America, at the organizations annual meeting in 1936, that Edith foreshadowed this exact book and everything we do here at the Xerces Society in a lecture titled Without Benefit of Insects.

In that talk Edith discussed the wholesale destruction of insect life that had resulted from the new insecticide products that were being brought to market, and commented on how in attempting to control pests, we were destroying bees and beneficial insects. She challenged the assembled scientists to imagine a very different world in the year 2000, when she predicted that the president of the United States would issue a proclamation declaring that land areas at regular intervals throughout the country would be maintained as Insect Gardens, directed by government entomologists. These would be planted with milkweed and other plants that could sustain populations of butterflies and bees. She then predicted that at some time in the future, Entomologists will be as much or more concerned with the conservation and preservation of beneficial insect life as they are now with the destruction of injurious insects.

Although the exact year she predicted turned out to be slightly early, Edith was ultimately right. In the summer of 2015, after extensive behind-the-scenes talks between the White House, Xerces, and other conservation groups, President Barack Obama did indeed release a first-of-its-kind memorandum. It called upon all federal agencies to do two things:

- To develop comprehensive conservation plans that would protect and restore habitat for bees and butterflies at federal facilities and on federal lands

- To offer financial incentives for the restoration of pollinator habitat on private lands, especially farmlands

The president also issued a challenge to the conservation community to help foster a million new pollinator gardens in residential yards and business campuses across the country an effort Xerces is supporting through our Bring Back the Pollinators Garden Campaign ( xerces.org/bringbackthepollinators ).

While the accuracy of Ediths prediction is both haunting and heartening, amazingly she was not alone in pioneering the call to create habitat for pollinators. Twenty years earlier, in fact, Iowa polymath Frank Chapman Pellett established near his childhood home what may have been the first large-scale bee garden in the United States. Although formally trained as a lawyer, Frank eschewed the basic trappings of prosperity, choosing instead to live in Gandhi-like midwestern simplicity in a small, plain farmhouse. There he researched tomato gardening, devoted countless hours to bird watching, and meticulously documented and cultivated the preferred wild pollen and nectar sources of his honey bees.

His ceaseless hours of observation resulted in the 1920 book American Honey Plants, possibly still the best publication of its kind in existence. In another book, Our Backyard Neighbors, Frank wrote of himself and his pollinator garden in the third person, saying, There were many wild flowers, such as asters and goldenrod, crownbeard and rudbeckia, which the neighbors regarded as weeds, but which the Naturalist guarded with jealous care.

Along with Edith Patch and Frank Pellett, the late Canadian scientist Dr. Eva Crane played one of the largest roles in further inspiring early thinking about pollinator gardens. Although she was formally educated as a quantum mathematician and nuclear physicist, the gift of a beehive in 1942 (as a supplement to wartime sugar rationing) led Eva to devote the next five decades of her life to publishing nearly 200 books and articles on honey plants and indigenous beekeeping.

Her writing was based on her field research in more than 60 countries, where she often lived under primitive conditions, even in her later years. Her rigorous and exacting books, such as the Directory of Important World Honey Sources, are the most comprehensive attempts of their kind to document the nutritional value of pollen and nectar from thousands of species of plants, as well as those plants potential honey yields.

In their own ways each of these deeply inquisitive champions of pollinator habitat inspired small communities of beekeepers and conservationists to see the landscape through a different lens. Plants previously scorned as weeds and unproductive waste areas on farms began to have value to at least a small segment of people, even as urbanization and agriculture intensified with enthusiasm.

By 1950 even the USDA Soil Conservation Service, the agency most responsible for saving American agriculture from itself during the Dust Bowl, recognized the value of pollinators. It distributed a simple educational bulletin to Midwest farmers, featuring an illustration of bumble bees flying between a hedgerow and a clover crop with the earnest title Wild Bees Are Good Pollinators. The bulletin lists important habitat areas on the farm to protect for pollinators, including stream banks, woodlots, shelterbelts, and field borders. For good effect the bulletin even features an illustration of a bag of clover seed with a dollar sign across its front.

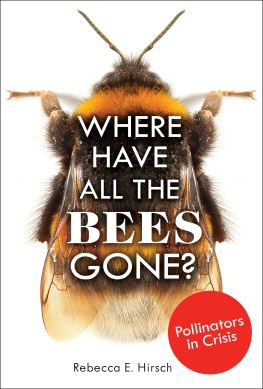

Surprisingly, the dawn of the environmental movement brought little attention to pollinators during the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, although countless other important conservation issues finally received some long-overdue attention. Only when large-scale honey bee losses began to make headlines in 2006 did the conservation community again focus much on the role of pollinators. By that time several bumble bee species in the United States were dwindling toward extinction, and once-common monarch butterfly populations were in free fall. Now books and articles about pollinator conservation are everywhere. For those of us at Xerces who have been working on and writing about pollinators for decades, this long-overdue attention is gratifying and energizing.

The spiritual tradition of this particular book descends from Patch, Pellett, and Crane, but also from John Muir, Aldo Leopold, Rachel Carson, and many others. These are the writers who inspired us here at Xerces in our youth and early in our careers, and who ultimately helped bring us all together as the big extended family that we are today. Our goal, like that of the conservation writers who preceded us, is not just to preach the gospel, but also to invite you into the tribe. We hope that you will join us.

The initiation is simple: just plant flowers.