To Rick, for never-ending support

Text copyright 2017 by Rebecca E. Hirsch

All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.

Twenty-First Century Books

A division of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc.

241 First Avenue North

Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA

For reading levels and more information, look up this title at www.lernerbooks.com.

Main body text set in Cheltenham ITC Std 11/15.

Typeface provided by International Typeface Corporation.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hirsch, Rebecca E., author.

Title: De-extinction : the science of bringing lost species back to life / by Rebecca E. Hirsch.

Description: Minneapolis : Twenty-First Century Books, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Audience: Ages 13 to 18. | Audience: Grades 9 to 12.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016019335 (print) | LCCN 2016051477 (ebook) | ISBN 9781467794909 (lb : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781512428483 (eb pdf)

Subjects: LCSH: Extinct animalsCloningJuvenile literature. | Rare animalsCloningJuvenile literature. | Extinct animalsGeneticsJuvenile literature. | DNA, FossilJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC QL88 .H57 2017 (print) | LCC QL88 (ebook) | DDC 591.68dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016019335

Manufactured in the United States of America

1-38652-20544-9/14/2016

9781512439021 ePub

9781512439038 ePub

9781512439045 mobi

Contents

Chapter One

The Last Bucardo

Chapter Two

Resurrecting the Mammoth

Chapter Three

Mammoth 2.0

Chapter Four

The Great Passenger Pigeon Comeback

Chapter Five

Hopes and Fears

Chapter Six

The Frozen Zoo

Chapter One

The Last Bucardo

An air of excitement filled the room as the team readied for surgery. The date was July 30, 2003, and everyone was hoping for the best. With great care and skill, the team prepped the patienta pregnant goatand surgically delivered a 4.5-pound (2-kilogram) female kid. The newborn animal was a wild goat known as a bucardo.

The birth was a momentous achievement because, technically, the bucardo was extinct. The last of its kind had died three years earlier in the mountains of northern Spain. But there in the operating room, at a Spanish research facility, the bucardo had just flickered back into existence.

The newborn bucardo looked normal and had a normal heart rhythm, yet something was wrong. As Spanish wildlife veterinarian Alberto Fernndez-Arias cradled the newborn in his arms, he could see that the animal was struggling to breathe. After only ten minutes, the baby bucardo died. Everyone in the room grew quiet. One person cried.

With that death, the bucardo once again passed into extinction.

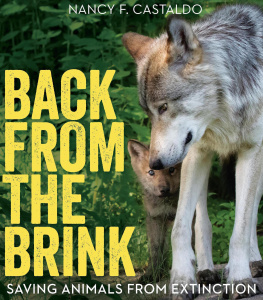

This illustration of a bucardoa type of wild goatappeared in an 1898 book called Wild Oxen, Sheep, and Goats of All Lands, Living and Extinct . At the time of the books publication, bucardos had nearly been hunted to extinction.

Dolly and Celia

For thousands of years, bucardos ( Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica ) roamed the Pyrenees. These mountains straddle the border between France and Spain. The animals had chestnut-colored coats of short, thick wool. Male bucardos sported long, ridged horns that curved backward in gentle arcs. The females, with smaller horns, looked similar to female deer.

Bucardos were well adapted to life in the mountains. They could clamber up steep cliffs and survive cold, snowy winters. During summer they lived high on the slopes, eating alpine plants. In winter they moved down to the valleys, where males and females mated. In spring females retreated to remote areas of the mountains to give birth.

Six hundred years ago, bucardos were common in the Pyrenees. Humans had little interaction with them. But their safety began changing when European game hunters discovered bucardos. Hunters shot the animals and mounted their heads on walls. Male heads, with their large, curving horns, were especially desired as trophies. In the nineteenth century, hunters from all over Europe traveled to the Pyrenees to seek this trophy animal, and the number of bucardos dwindled. Domestic livestock, brought into bucardo territory by farmers, may also have contributed to the decline. Some scientists theorize that farm animals competed with bucardos for food or passed on deadly diseases to them.

By 1900 fewer than one hundred bucardos were left. In the early twentieth century, the Spanish government created Ordesa National Park, which is off-limits to hunting. In the 1950s and 1960s, Spain created more wildlife refuges. Still the bucardos numbers declined. By 1989 only about a dozen bucardos were left. In 1996 just three remained, and that year, two of them died natural deaths. Scientists realized the animal could not be saved from its slide into extinction. That was the hardest year, said Fernndez-Arias.

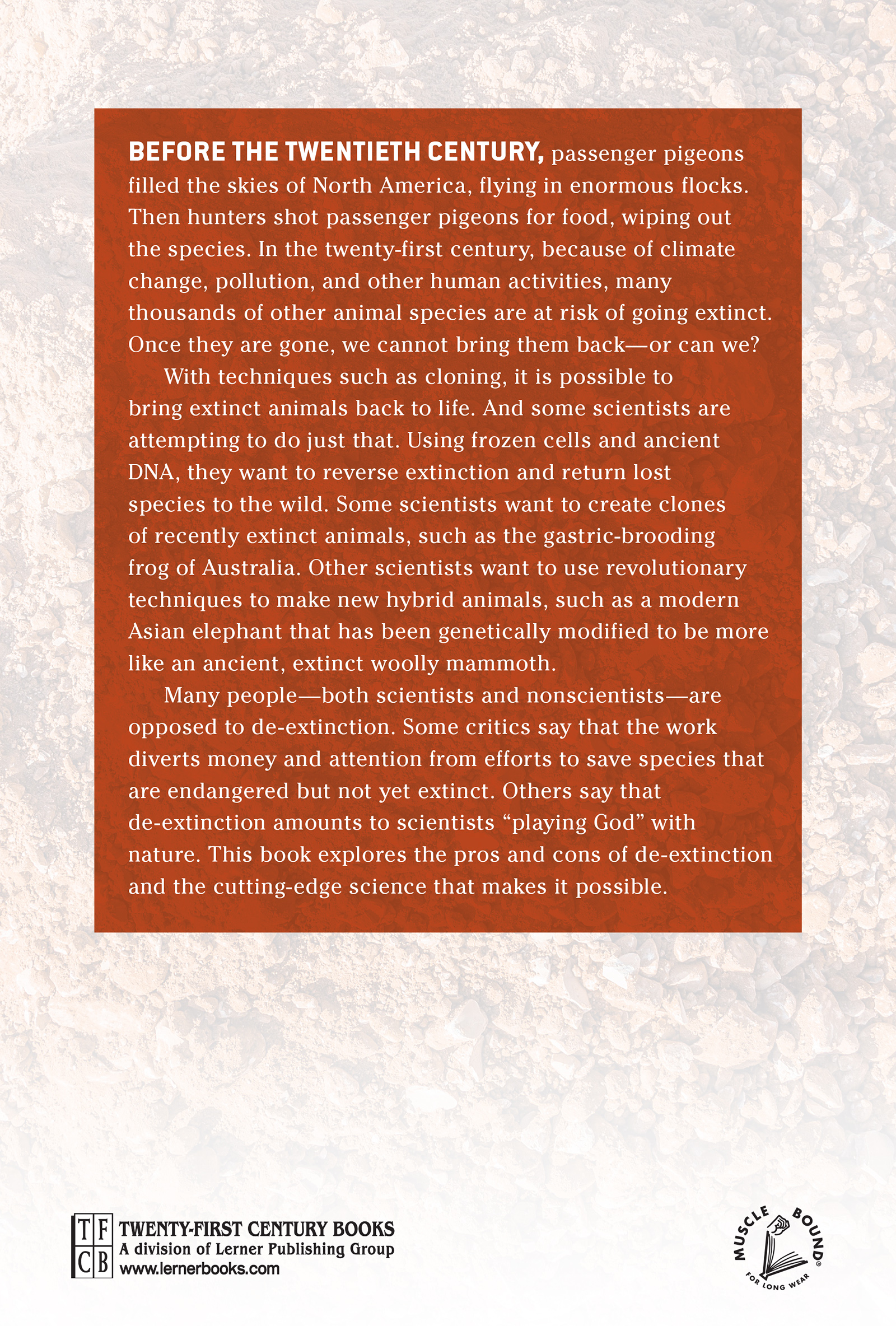

Also in 1996, Scottish scientists achieved a historic first, cloning a sheep that they named Dolly. A cloned animal is a living animal created not by sexual reproduction but by manipulating reproductive cells in a laboratory. Clones differ from other animals in the way they acquire their genes (the material inside cells that controls how an organism grows, behaves, and reproduces). Organisms produced via sexual reproduction get half their genes from one parent and half from the other. Clones, on the other hand, have the exact same genes as only one parent. The birth of Dolly the sheep, the first mammal produced by cloning, was a scientific leap that made news around the world. That achievement brought hope that the bucardo could also be cloned to save it from extinction.

Dolly the sheep, who lived from 1996 to 2003, was the first mammal produced through cloning. De-extinctionists realized that the same techniques used to create Dolly could be used to revive extinct species.

In April 1999, Fernndez-Arias led a team into the mountains to find the last bucardo, a female nicknamed Celia. The scientists took samples of Celias blood and feces, scraped some skin from her ear for genetic testing, and snapped a collar on her to track her movements via radio. Then they released her back into the wild.

On January 6, 2000, Celias radio collar gave a long, sustained beep. That signal meant that Celia was no longer movingshe had died. When researchers found her, they saw that her skull had been crushed by a fallen tree. With Celias death, the bucardo had passed into extinction.

A species or subspecies (a subdivision of a species) becomes extinct when all of its kind have died. But in the bucardos case, although Celia had died, some of her cellsextracted from her blood and skin in 1999still lived. Fernndez-Arias and his team had frozen the cells in liquid nitrogen at a temperature of 321F (196C). Scientists wondered, What if they could use the cells to clone Celia and bring the bucardo back to life? Could they reverse extinction?