ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book finally came to fruition thanks to everyones steadfast dedication and to the people who have supported this project along the way. I thank Alex Hinton for having the good instinct to connect me with Fran Mascia-Lees about the possibility of the Anthropology Department of Rutgers-New Brunswick hosting a symposium on extinction that would draw on the strengths of the disciplines subfields. Frans enthusiastic support and the generosity of the entire Anthropology Department enabled us to have a sustained dialogue about a formative subject of anthropology, an issue of major global significance, and a universal experience of human being. I am indebted to all who participated, including those who do not appear in these pages but who enriched our discussion with their knowledge and insights: John Colarusso, David Hughes, Rob Scott, and Rick Schroeder. I also thank the Rutgers University Research Council and the Center for the Study of Genocide and Human Rights at Rutgers-Newark for additional support. I owe my gratitude to Rebecca Tolen, Molly Mullin, and an anonymous reviewer for their wise and thoughtful suggestions.

And finally I will add, on a very personal note, that during the groups preparation for the symposium, the theme of extinction had become a palpable mood in my home as my mother, Inez Naples Kemptner, who was visiting my family for a last time in the summer of 2008, had grown too weak from cancer to return to Seattle and died in New Jersey that August. She would have been so proud to see this book in print.

1. A SPECIES APART

IDEOLOGY, SCIENCE, AND THE END OF LIFE

Janet Chernela

In recent decades science has reached a critical juncture that calls our attention to its fundamental character and the contradictions within it. The crisis was brought about by the observation, by some scientists, that the Earth is facing a massive sixth extinction, one that may have been provoked by human activity. Reaction to this revelation has been complex; it points to some of the ways in which science is influenced by and inextricably integrated into the social fabric.

The degree to which science, as a pursuit of knowledge, is emancipated from the ideological underpinnings of society is an ongoing debate within the social and philosophical disciplines (Althusser 1971; Eagleton 1991; Giddens 1979). Theoretically, science and ideology represent two kinds of knowing, of which the first is open and the second closed. This profound difference has far-reaching implications, suggesting, among other things, that science reaches toward the unknown, whereas ideology continually reproduces itself. From the viewpoint of its proponents, science is an enterprise that not only is open to questions, but is built upon them.

In contrast, ideologies, the idea systems that we rely upon to make sense of the world, are (by definition) closed to challenge. They are intellectual strategies that allow us to organize chaotic phenomena into coherent conceptual schema. Although the reach of any ideology may be sweeping and capable of explaining such matters as, say, human nature, ideological schema are nevertheless based upon a few generating assumptions. Insofar as they are presented as universal or natural, ideologies discourage, rather than encourage, questioning.

The very act of employing the plural form ideologies undermines the totalizing power of any single scheme. The plural is important in this context, because an important source of an ideologys power is its ability to appear as the only option. Anthropological inquiry is, however, based in comparison. It is the comparative viewpoint, present in anthropology since its founding in the nineteenth century, which enables its practitioners to regard all ideologies with the same degree of arbitrariness and to reflect on some of the ideologies that lie at the basis of Western thought and worldviews.

One of the ways in which science may serve society is by contributing to a belief in limitless possibility in which Man (First World, Western man, that is) is master of destiny, having attained this position through the domination and accumulation of knowledge. A fundamental tenet of this ideology is the definitive separation of humans from all other creatures, and the earned status of humans as inheritors of the Earths bounty. From this perspective, therefore, science may constitute part of the larger project of technological progress and Western hegemony that drives global economies of growth and celebrates human achievement.

Over the past two centuries, scientific accomplishment has provided a principal resource for optimism, confidence, and the celebration of Western achievement. That science has brought a sense of life, vitality, and possibility to the public has been apparent for some time. Its role in the forward motion of material accumulation and resource exploitation has been fundamental to its momentum. The science of extinctions, as findings and as sets of ideas, would thus appear to be an exception to the pattern.

A dramatic reduction in global biological diversity, brought about in part through activities deemed to be the fruit of advances in scientific knowledge, calls into question our assumptions about the scientific enterprise and the uses to which it is put. In this chapter, I briefly review the growing awareness of extinctions in order to consider what it tells us about the role of science in society.

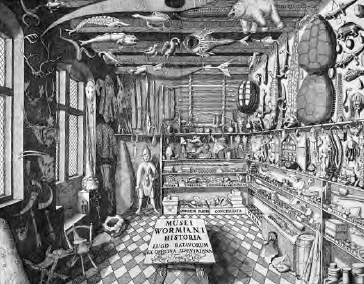

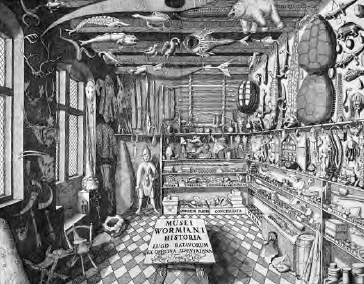

Icons of Extinction: Objets Morts

Visitors to the Wunderkammern and Cabinets du Roi (curiosity cabinets) of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries delighted in objets mortsthe dried, stuffed, and bottled remains that evidenced a mysterious past (Olalquiaga 2006). Contained among the collections of naturalia were unidentified, mystifying objects from excavations. As citizens of a newly found progress, Europeans were fascinated with things passed, or morts. The greater the contrast with the present, the more entrancing the object. By looking back at a past populated by beings of grotesque difference, humans could place themselves at the apical meristemthe growing tipof the future.

Figure 1.1. Ole Worms cabinet of curiosities. From Museum Wormianum (1655), in the possession of the Smithsonian Institution Libraries.

The discovery of the skeletal remains of the American mastodon in 1705 served as evidence of the existence and disappearance of an intriguing species. Exhibits of mastodons captivated Europe during the eighteenth century. In the American colonies the discoveries of mastodons coincided with a growing independence movement and a new national identity. In 1801 Thomas Jefferson, an avid collector of fossils and a student of extinctions, joined Charles Willson Peale in an expedition to exhume mastodon bones in upstate New York. The achievement was regarded as one of the important events in the history of American science and Peale mounted the gargantuan skeleton in his Philadelphia Museum, one of the first natural history museums in the United States. The specimen, displayed along with a murderers finger and an eighty-pound turnip, was considered the museums first successful attraction. The sensation was auctioned in 1849 and sold to bidder P. T. Barnum.