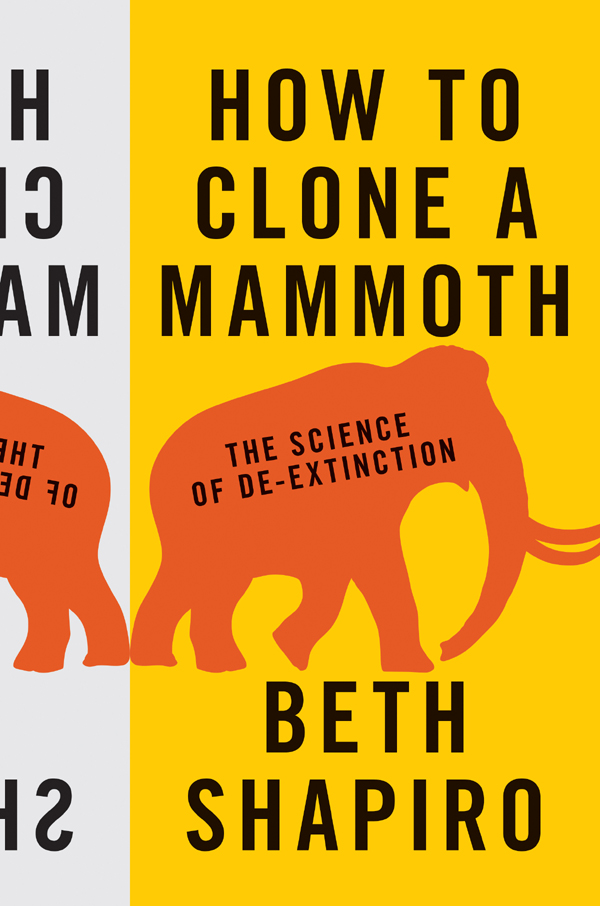

HOW TO CLONE A MAMMOTH

HOW TO CLONE A MAMMOTH

THE SCIENCE OF DE-EXTINCTION

BETH SHAPIRO

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2015 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-15705-4

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Baskerville Original Pro and Trade Gothic

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For my children, James and Henry, who willinherit whatever mess we make.

PROLOGUE

The first use of the word de-extinction was, as far as I can tell, in science fiction. In his 1979 book The Source of Magic, Piers Anthony describes a magician who suddenly finds himself in the presence of cats, which, until that moment, he had believed to be an extinct species. Anthony writes, [The magician] just stood there and stared at this abrupt de-extinction, unable to formulate a durable opinion. I imagine that this is precisely how many of us might react to our first encounter with a living version of something we thought was extinct.

The idea that de-extinction might actually be possiblethat science might advance eventually to the point where extinction is no longer foreveris both exhilarating and terrifying. How would de-extinction change the way we live? Would de-extinction provide new opportunities for economic growth and galvanize global conservation efforts? Or would it lull us into a false sense of security and ultimately increase the rate of species extinction?

The year 2013 saw de-extinction become its own new branch of science, at least according to the Times.traits and behaviors of the extinct species will be genetically engineered into living species. The living species would then gain the adaptations necessary to thrive where the extinct species once did. Will society, however, respond favorably to de-extinction if the goal is not to bring back an actual mammoth, dodo, or passenger pigeon?

Piers Anthonys novel was eerily prescient with regard to our reaction to de-extinction. Immediately after his magician accepted that de-extinction was possible and, presumably, in the midst of forming an opinion about it, Anthonys magician had another thought. Anthony writes, If [the magician] killed these animals, would he be re-extincting* the species?

* A warning to grammarians: In this sentence, Anthonys magician provides what is perhaps the earliest example of that awkward moment when, while discussing some aspect of de-extinction, it suddenly becomes clear that there is no satisfying way to complete a thought without offending people like you. How should one designate a species that has been brought back to life? While de-extinction seems perfectly logical with reference to a process, to refer to the end-result of that process as de-extinct seems inappropriate. De-extincted, while more logical, is painful to write down, much less to say out loud. I prefer unextinct to de-extinct, as unextinct seems to describe the state of being, rather than the process of getting there. One might say, for example, The mammoth is unextinct. Of course, The mammoth is no longer extinct is certainly sufficient.

What, then, is the present participle? I shudder when I say that George Churchs lab is de-extincting the mammoth. My reaction to the phrase, however, has nothing to do with the science. At the first formal scientific discussion of de-extinction, some of us suggested using resurrection and its various conjugates, as in, We are resurrecting extinct species. While resurrect makes perfect grammatical sense, however, its religious connotations seemed misleading. Certainly, De-extincting, is terrible, as is re-extincting. Yet, here we are. While it takes longer to say it, perhaps we should stick with something that is simple to understand and entirely inoffensiveat least grammatically: We are developing the science necessary to bring extinct species back to life.

Many of the people with whom I interact believe that de-extinction is inevitable. Ill admit, however, that this is a biased sample of the population, and that most people are likely to care about de-extinction only insofar as it might affect them personally. Some people of course love the idea of de-extinction. They may be swayed and enthused by the idea that resurrected species might improve wild habitats. Or they may just want the opportunity to see and touch a mammoth. Other people, including very sensible and intelligent people, hate the idea of de-extinction, citing both the high cost of resurrecting extinct species and the myriad risks of reintroducing organisms into the wild whose environmental impacts arebecause they are extinctnecessarily unknown. Those people who fear de-extinction the most, like Anthonys magician, take solace in its reversibility. This worries me. It is undoubtedly true that history repeats itself and that, if need be, we could re-eradicate any species we brought back. However, our goal as scientists working in this field is not to create monsters or to induce ecological catastrophe but to restore interactions between species and preserve biodiversity. If we do arrive at a time when science makes it possible to resurrect the past, it might take years or decades to see the results of this work. I certainly hope we do not simply turn around at the first signs of imperfection and destroy what we worked so hard to accomplish.

Certainly, if we are to make room for extinct speciesor for hybrids of extinct and living speciesin the real world, we as a society will have to alter our attitudes, our actions, and even our laws. Science is paving the way to resurrect the past. The road, however, will be long, not necessarily direct, and certainly not smooth.

With this book, I aim to provide a road map for de-extinction, beginning with how we might make the decision about what species or trait to resurrect, traveling through the circuitous and often confusing path from DNA sequence to living organism, and ending with a discussion about how to manage populations of engineered individuals once they are released into the wild. My goal is to explain de-extinction in a way that separates science from science fiction. Some steps in the de-extinction process, such as finding well-preserved remains of extinct species, will be relatively simple to complete. Others, however, such as cloning extinct species, may never be feasible. My perspective, as a scientist who is actively involved in de-extinction research, is that of an enthusiastic realist. I believe that de-extinction is in many cases scientifically and ethically unjustified. However, I also believe that de-extinction technology has great potential to become an important tool for conserving species and habitats that are threatened in the present day. If that seems paradoxical, read on.

HOW TO CLONE A MAMMOTH

CHAPTER 1

REVERSING EXTINCTION

A few years ago, a colleague of mine practically bit my head off for getting the end date of the Cretaceous period wrong by a little bit. I was presenting an informal seminar about my research to graduate students at my university, which at the time was Penn State. My seminar was about mammothsin particular, about when, where, and why mammoths went extinct, or at least what weve learned about the mammoth extinction by extracting bits of mammoth DNA from frozen mammoth bones. Before talking about this very recent extinction, I opened with a discussion of older and more famous extinctions. My offending slide cited the date for the end of the Cretaceous period and beginning of the Paleogene, also known as the K-Pg boundary and best known as the time of the extinction of the dinosaurs, at around 65 million years ago. That date, I was told, was inexcusably imprecise. The K-Pg boundary occurred 65.5 0.3 million years ago (at least that was the scientific consensus of the time), and I was

Next page