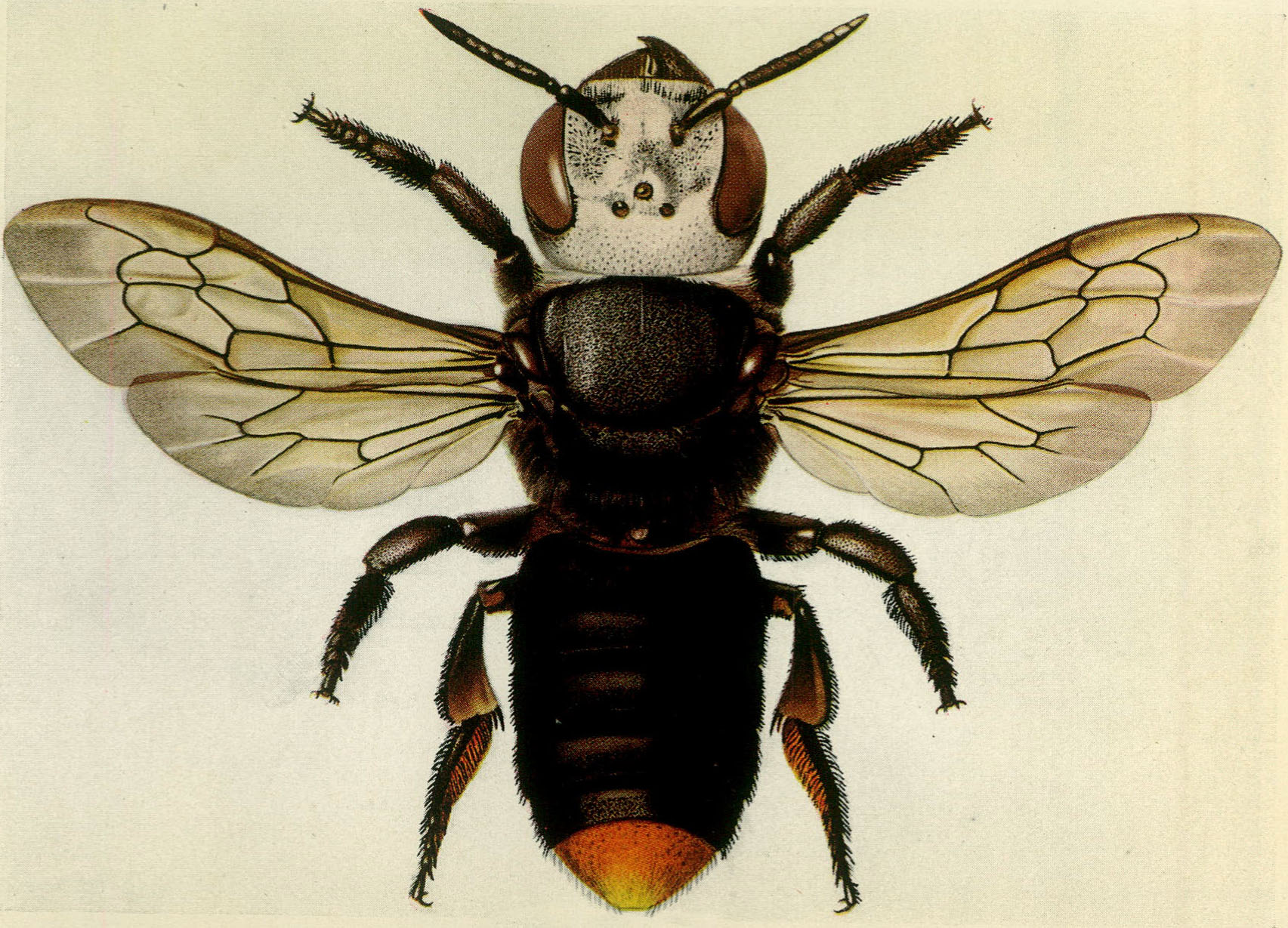

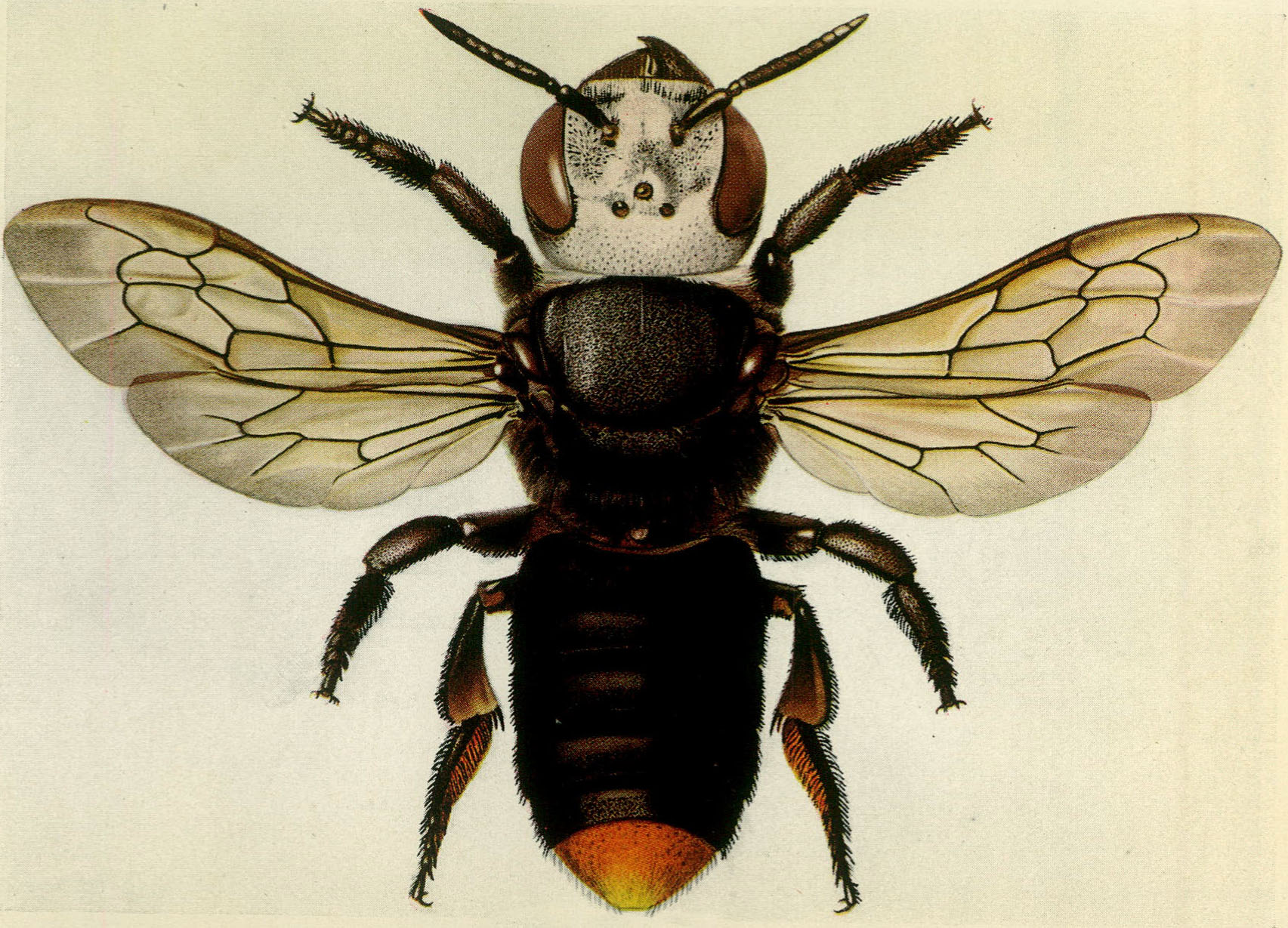

Megachile Senex

The World of Bees

Gilbert Nixon

Illustrations by Arthur Smith

Acknowledgements

In writing this book, I have been helped by contributions that other entomologists, past and present, have made to our knowledge of bees. In borrowing from their work, I am deeply conscious of my debt to them.

I have had other assistance, tooof a practical kind. To Maurice Burton in particular I offer my sincere thanks for persuading me to write a popular book about bees and for helping me afterwards by reading a part of the typescript and making many valuable suggestions. To Everard Britton I also express my indebtedness. He read several chapters of the typescript and helped me to explain more clearly certain aspects of the book that might otherwise have remained obscure. I am also grateful to members of the staff of the Bee Research Department, Rothamsted Experimental Station, for drawing my attention to statements that required qualification. Lastly, my special thanks are due to my wife for reading the proofs and for never failing, at any time, to give me the encouragement I often needed.

Arthur Smith, who did the illustrations, knows how highly I esteem his beautiful work. He earns my thanks for giving me the benefit of his artistic ability.

G ILBERT N IXON

List of Illustrations

Male leaf cutter bee, Megachile willoughbiella

Andrena nitida , female, a solitary bee

Female of cuckoo bumble-bee, Psithyrus vestalis

Chapter One

What Is a Bee?

My interest in bees was alive when I was very young. First adventures with them are for the most part forgotten, but a few impressions have remained sharp and clear in my memory. There was, for instance, the first big bumble-bee that ever became my prisoner. I had it beneath an upturned wineglass that had been thrown out because of a broken stem. I can remember, too, the fragrant scent of the brown bees that were fond of sunning themselves on the trunk of an old cherry tree towards the end of a spring afternoon. I used to catch them with a jam jar from which I soon learnt to pick them out with my fingers. Being young and holding a small live object in my fingers, I soon discovered that this particular bee had a pleasant smell.

Then there was the red bee, a most desirable little creature that came to the flowers of the gooseberry. Although its movements seemed leisurely, it had a knack of slipping off quickly out of reach of my jam jar. Even more of a prize was the black bee that bad the habit of hovering motionless over the flowers of the polyanthus before it would settle, with the utmost grace and lightness, to take a sip of nectar.

Years later I learnt that my red bee had once been christened with the Latin name Andrena armata , and that my black bee was known as Anthophora pilipes . Another thing I found out about them was that they were the females of their kind, and that I had always known but not recognized their mates, who were plain brown in colour and decidedly dingy by comparison.

I was also well acquainted with the honey-bee, though for some reason of obscure origin I did not care for it as much as I liked its wild relatives. It was the intruder that had no place in my private and very exclusive world of bees. Had it not come from a hive where it was tended by human and unhallowed hands? This much I had been told, though the unhallowed part I added myself. But with the wild bees it was very different; there was hardly a person about me who even so much as suspected their presence. So that I felt that I alone, with the nave ignorance of the very young, was privileged to claim them for my own and probe their secrets.

Since those early days, bees have charmed and delighted me. I have even dropped my snobbish disdain for the honey-bee and become one of her most slavish admirers.

It may sound a little odd perhaps, but for many years I knew more about the habits of certain bees than how many different kinds of bees there were or how it was possible to distinguish one sort from another, apart from obvious differences in size and colour. It was a long time before I could bring myself to abandon my first love, the butterflies and moths, and make a collection of bees instead. The changeover was made easier through the gift of a hand lens that a sympathetic father fished out of a drawer of odds and ends.

The lens had a low magnification but it nevertheless gave my bees a new appearance, a quality of form and colour and texture that hitherto they had not possessed. It was exciting to see whether a small black bee, a bare quarter of an inch in length, had a round face or an oval face, to see whether the hairs that clothed its body were long or short and to decide whether or not the middle part of its bodythe thoraxhad a greenish tint.

This was my first introduction to insect classification and it fascinated me. An eminent entomologist, Edward Saunders, long since dead, had gathered together in a book called Hymenoptera Aculeata all that was known about the bees of the British Isles and had pointed out with great technical skill how the different kinds or species could be distinguished one from another. This book I managed to buy; I valued it like a Bible.

It is, I know, quite usual to make fun of those people who get pleasure from looking for the small details that make one species of insect different in appearance from another. Museum men they are called, concerned more with the anatomy of a dead insect than with the mystery that makes it, when alive, an object of occasional attention.

For me, however, the interest in bees was not suddenly shifted to their dried and pinned bodies. What did happen, though, is that I began to get more pleasure from observing live bees when I had some sort of idea how they looked when they were dead. The brown solitary bee that settled on the trunk of the cherry tree became more than just a brown bee with a fondness for basking in the sunshine. It became a particular kind of bee with its own special characteristics and a name by which it could always be known.

When I first began to make a collection of bees, I was already aware of certain rather obvious facts concerning the behaviour of some of them. If you love insects, as I did as a child, you just cannot help noticing the sort of thing they do openly, and when you see the same piece of acting repeated one summer after another, it acquires almost the invariability of the seasonal changes themselves. I knew that the red Osmia bees visited damp spots in the garden in order to scrape up a small pellet of clay which they bore off. Each year I could count on their coming almost to the same corner of the garden to get their loads of clay, though what they wanted the clay for I was never able to find out. It was years later, when I had learnt the names of the bees, that I was able to sort out the little bits of knowledge I had absorbed through long and close familiarity with them and attach these facts of behaviour to the actual species of bee they concerned.