***

In contemplating Natures being,

Know the One as many, seeing

In and outer coinciding,

Nothing in from out dividing.

Open secret, revelation!

Grasp it without hesitation.

Free of seeming truths confusion,

Revel in the serious game!

Separateness is the illusion

One and many are the same.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, English version by Aldyth Morris

Written in the rain

Whoever would become like a bee

who feels the sun

even through a cloudy sky,

who finds her way to a flower

and never gets lost,

to him the fields would lie in eternal radiance;

however short his life

he would rarely ever

complain.

Hilde Domin, from Nur eine Rose als Sttze

***

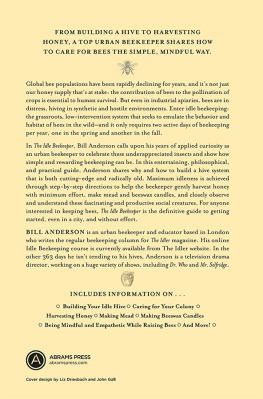

In a time when bee-keeping has become bee-losing, when the worldwide decline of the honeybee threatens global food production, the clear voice of Michael Weiler is a much needed addition to the growing choir of those concerned about bees. His book The Secrets of Bees: An Insiders Guide to the Life of Honeybees is an enlightening introduction for anybody interested in bees. At the same time it is a welcome resource for aspiring and seasoned beekeepers.

The author speaks with authority because he speaks from experience based on years of devoted observation. Goethe once famously remarked: In vain do we try to describe a mans character, but put his acts and deeds together and the character will reveal itself. He means that accurate observation of the facts will in time and of itself provide insights. To Michael Weiler this kind of observation has become second nature and he instructs us through his own example. Whenever he refers to graphs and statistics, it is in support of his detailed observations and not instead of them. We feel at all times carefully led and thoroughly informed by a presentation that takes us on a year-long journey.

Starting in spring, we become apprentices to a bee-master who patiently guides our gaze, sharpens our perception, points out details and explains connections we would otherwise miss. Led by his expertise we become familiar with the biography of a beehive, we witness the stages of catching the swarm, housing it, caring for and maintaining the hive. We are introduced to the miraculous reproductive capacity of the queen and follow the life-phases of the individual bee from egg to larva to worker. As a culmination our guide opens the door into the alchemical laboratory of nature. There we are initiated into the way bees transform transluscent nectar into the liquid gold that is honey. In all this we feel safe and satisfied because we are experiencing beekeeping as it should be.

At all times we have the impression that Michael Weilers beecraft has been learned from the bees themselves; that the beekeeping he describes is not imposed upon the hive but developed in collaboration with it. Most importantly, the symbiosis between beekeeper and bees he develops here is indeed a model for a new and mutually supportive relationship between humanity and Apis mellifera.

Horst Kornberger

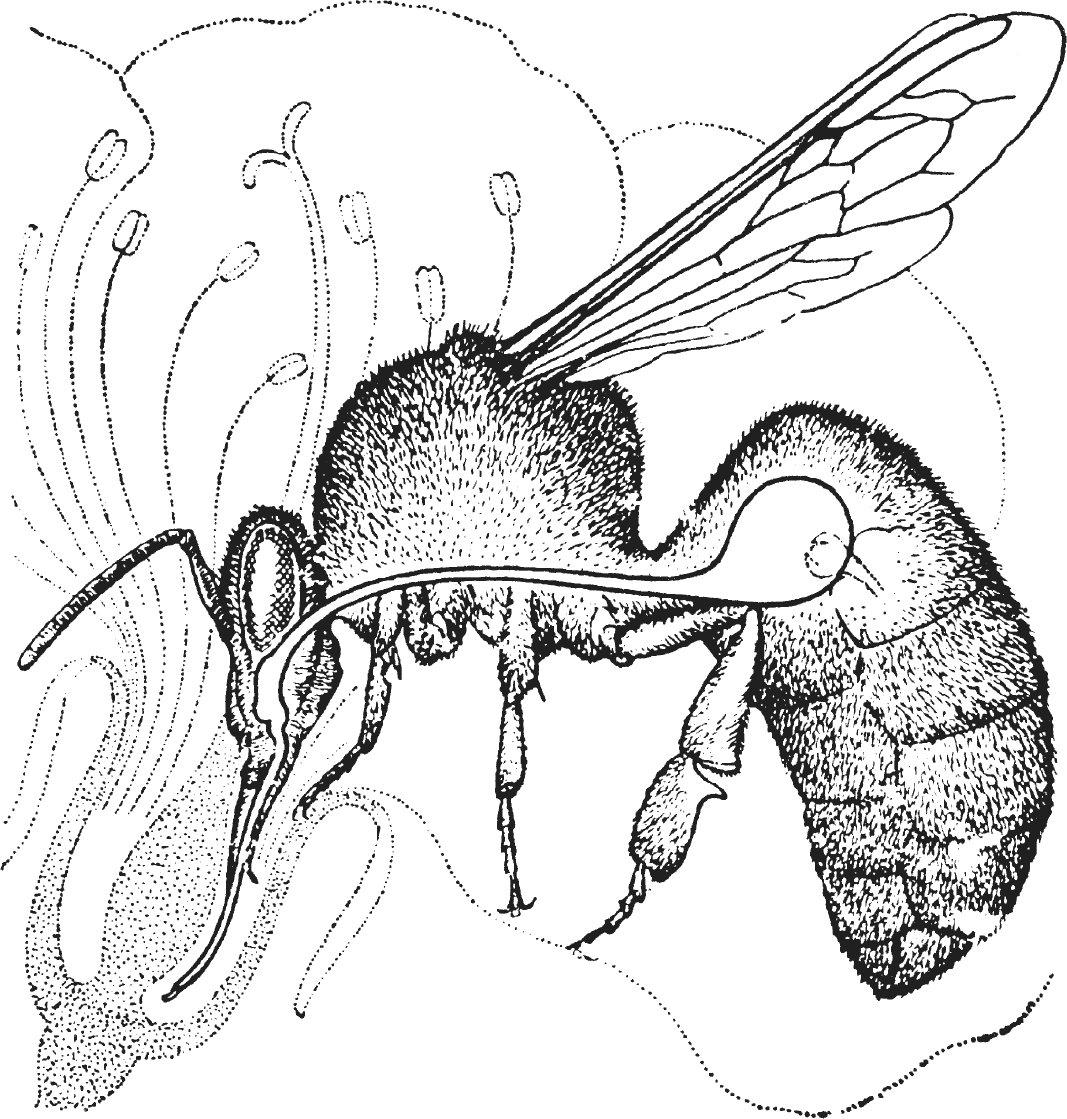

Figure 1. Bee gathering nectar on snowberry (Symphoricarpos)

It is a mild, dry, sunny spring day. A fruit tree stands in flower, a light breeze gently wafting its scent over us. From among the leaves a loud buzzing draws our attention. A large, flying insect is hurrying in wide curves from one flower to the next. After a while it flies away. At this time of year, it must have been a queen bumblebee. A more gentle humming persists, however, and on looking closer we see a lot of smaller bees active in the tree in the same way. All the while some are leaving whilst others are arriving, usually from the same direction. The bees busy themselves with the flowers, trying to get something from each one.

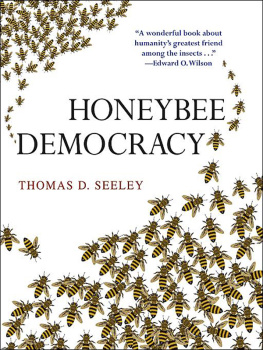

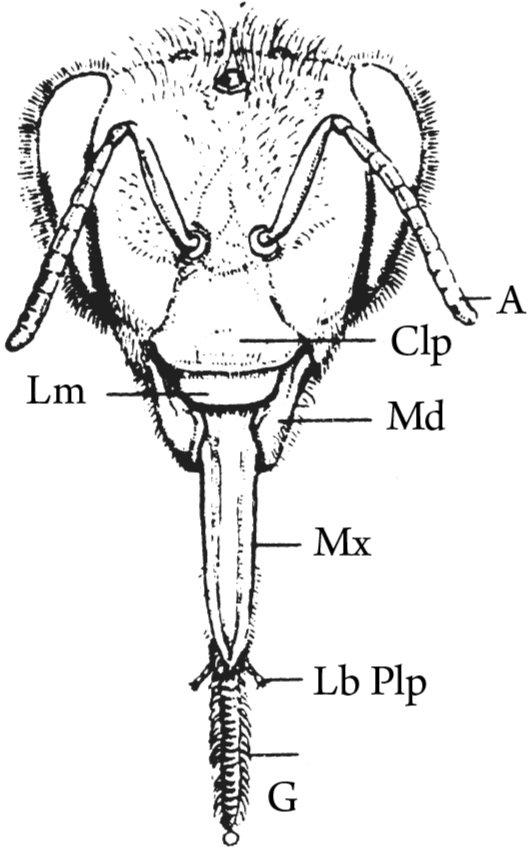

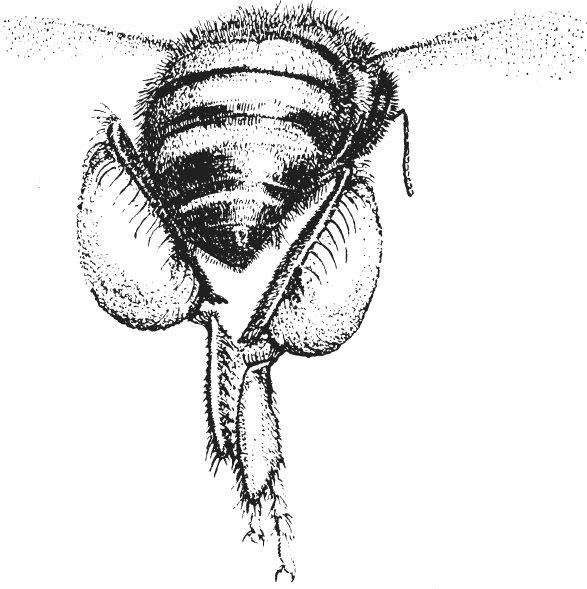

Figure 2. Worker bee showing the honey crop or honey stomach

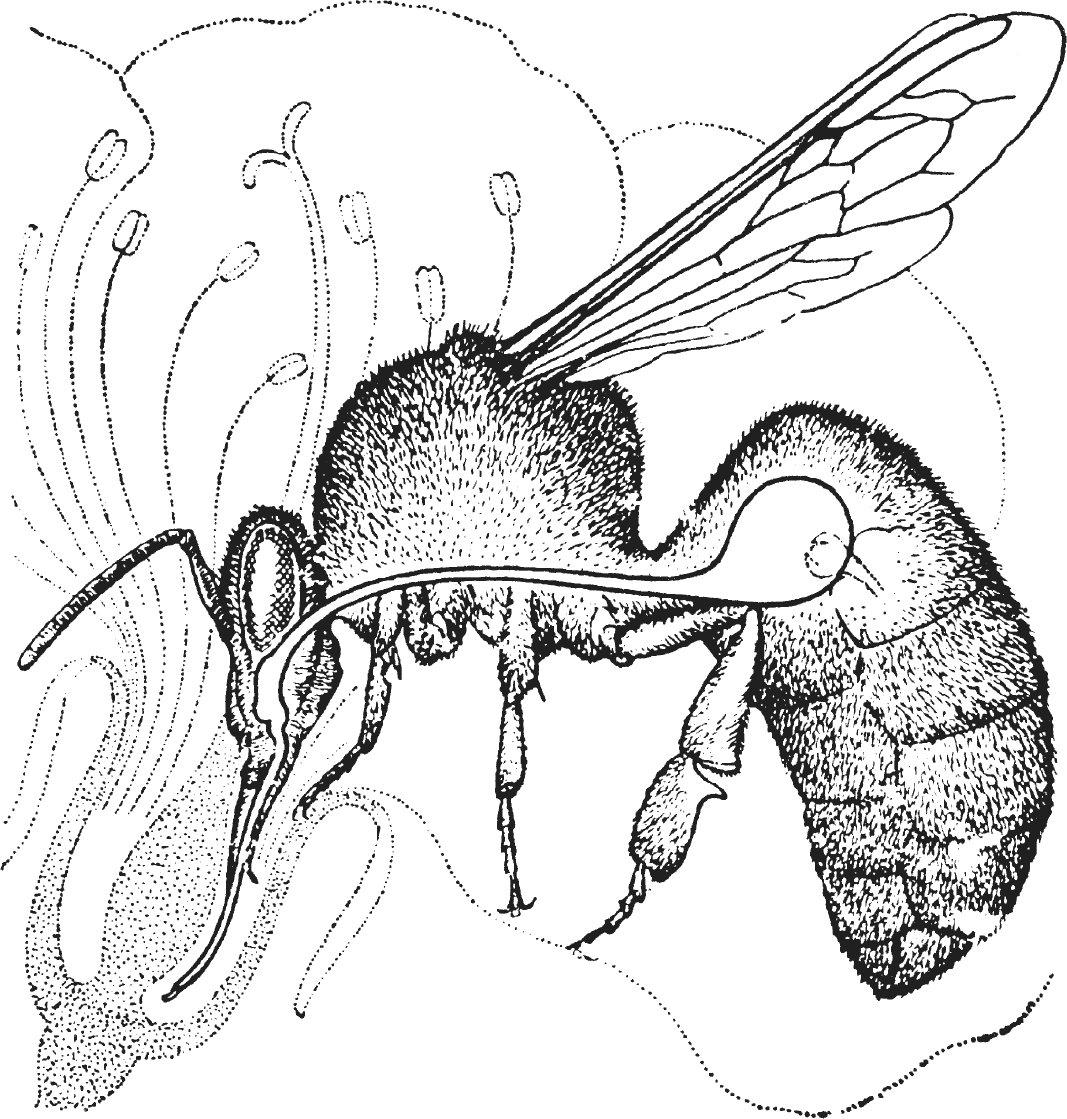

Figure 3. Head and mouth parts of worker bee:

A = antenna

Clp = clypeus

Lm = upper lip (labrum)

Md = upper mandible

Mx = lower mandible (maxilla)

Lb Plp = labial palp (tongue feeler)

G = tongue (glossa)

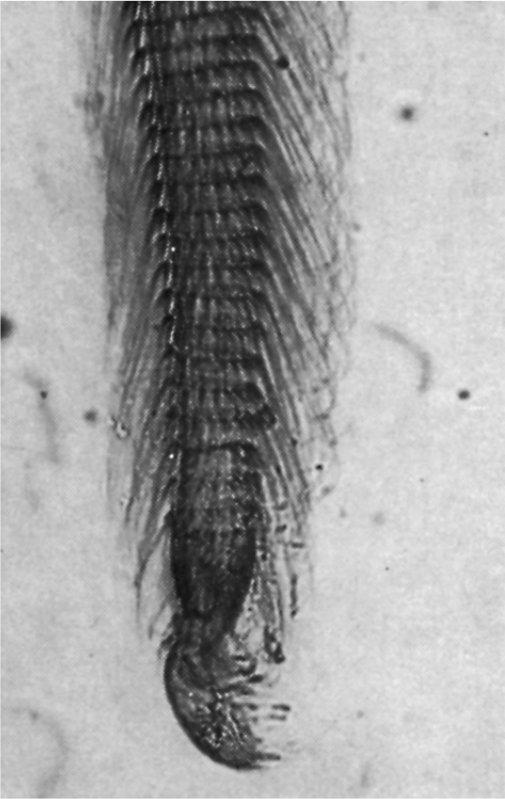

Figure 4. Tip of tongue (glossa) showing spoon (flabellum)

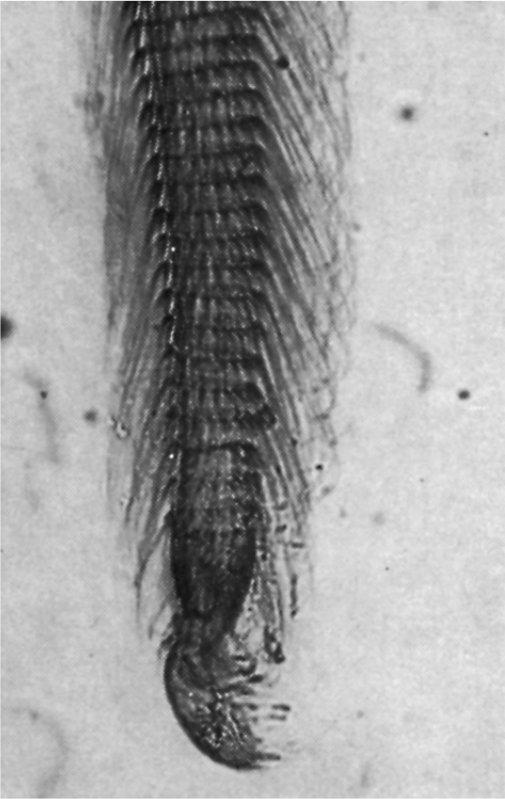

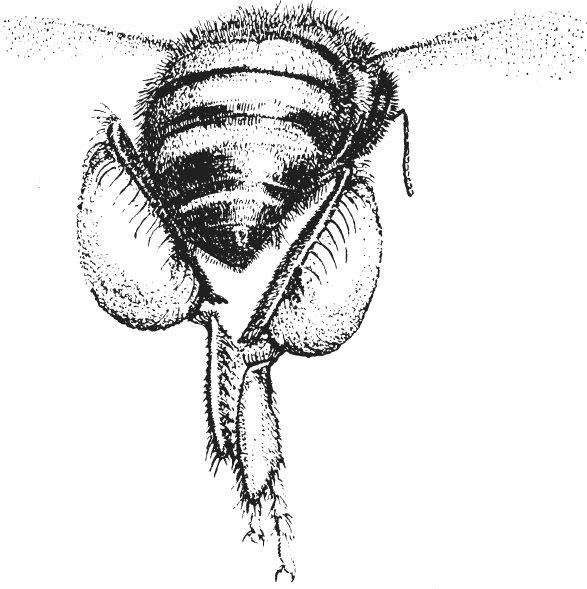

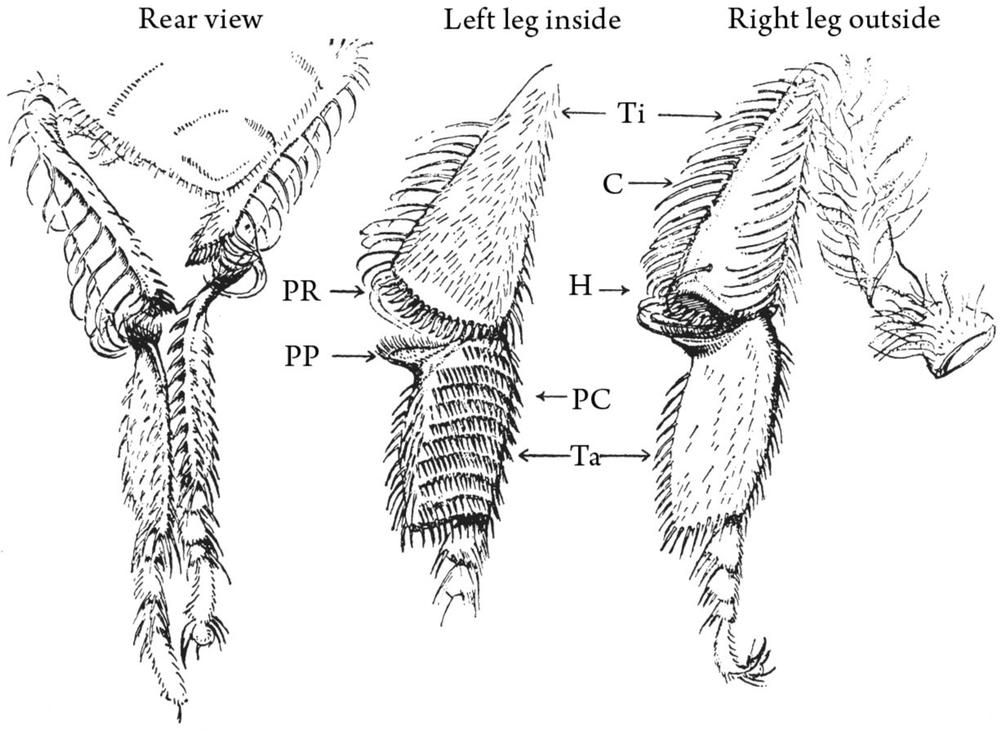

A long, narrow, mobile organ emerges from between two small, pincer-like jaws at the front of their heads and plunges deep inside a flower. When seen enlarged this shows a complex proboscis-like tongue that ends in the shape of a little spoon, which the bee uses to take up the nectar provided by the flower. At the same time other bees are repeatedly dusting themselves with flower pollen. It stands out brightly against the short hair on their furry bodies. Whilst a bee is flying to the next flower, it quickly sweeps its three pairs of legs alternately over its body, often hovering briefly in the air. This happens so fast that it is hardly noticeable. On each rear leg are devices like combs and rakes, and a fold into which the pollen is brushed. Beekeepers call these the pollen baskets.

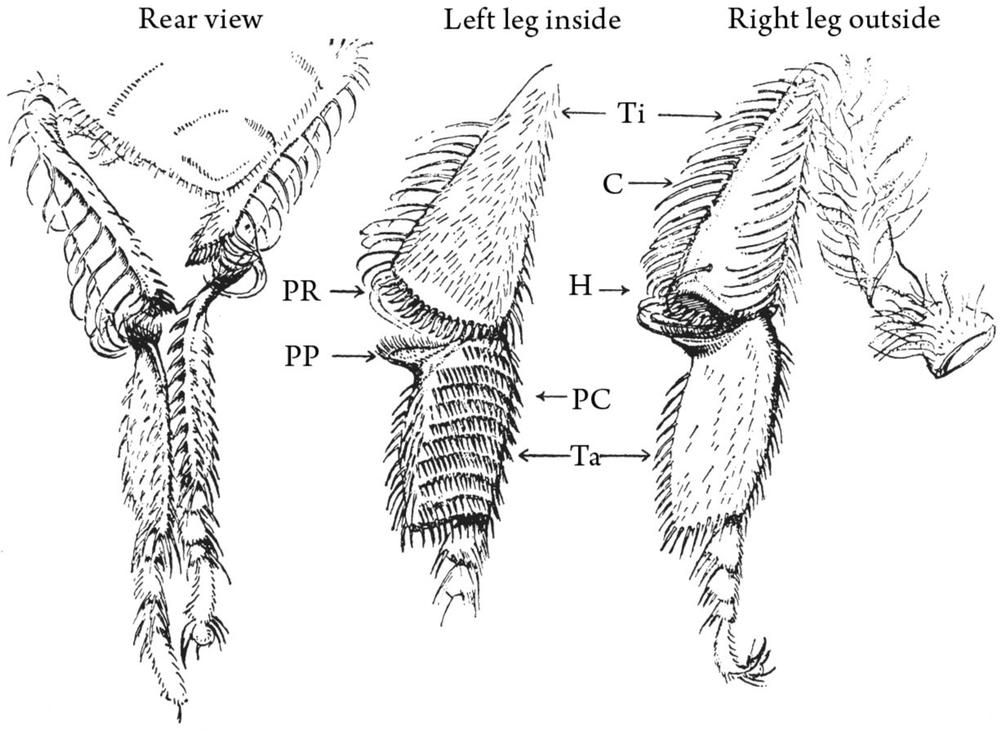

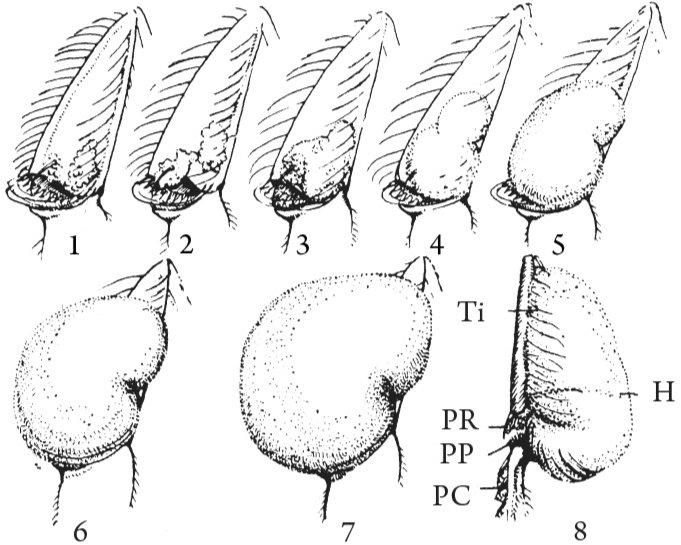

Figure 5. Pollen collection apparatus on the rear legs of worker bees

Ti = tibiae

Ta = tarsi

C = pollen basket (corbicula)

H = single hair

PR = pollen rake

PP = pollen press

PC = pollen comb

[From Zander and Weiss]

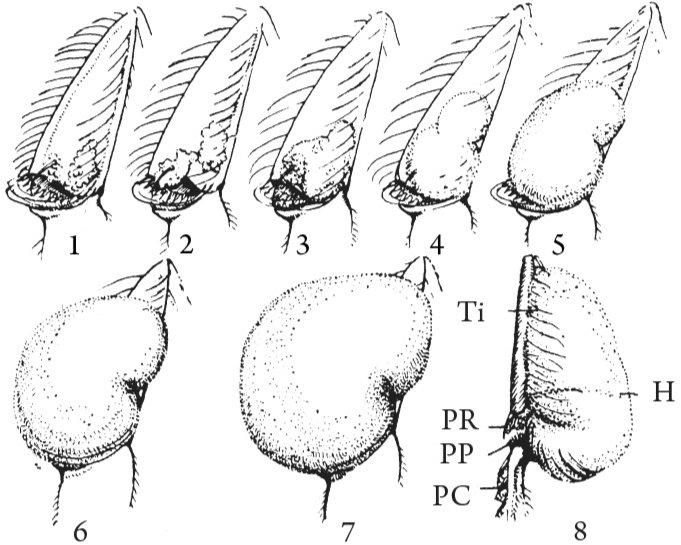

Figure 6. Forming the pollen load

Figure 7. Bee scraping pollen into loads

Not far from the fruit tree is a partly dammed-up stream. Water glistens on the mossy roots of the bushes lining its bank as bees alight constantly on the surface of the stream. Their abdomens move rhythmically, contracting and expanding in rapid succession as though pumping. They are collecting water. After a short time they fly away again.

Nearby is a chestnut tree on whose drooping branches there are still some fat buds with a resinous gleam. The bees are busy at work there too. They are biting off pieces of the bud resin with their mandibles and transferring them with rapid, skilful movements as little droplets on their rear legs, to the place where the pollen gatherers store their pollen loads. This bud resin is rather sticky and it is amazing how the bees manage to avoid getting sticky themselves.

On a foraging flight a honey bee flies at a height of between 28 metres (6 26 ft) above the ground and, depending on terrain and wind conditions, at a speed of about 68 m/sec (1418 mph). It carries 0.05 to 0.07 g of nectar, about half its body weight, in its honey crop (hereafter referred to simply as crop), which is a special compartment or sac of its anterior alimentary tract.