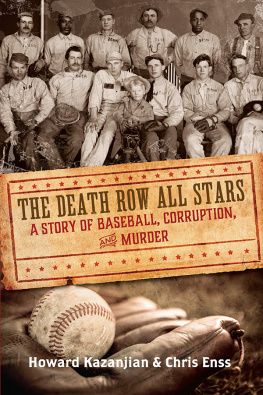

Copyright 2014 by Howard Kazanjian and Chris Enss

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, PO Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

TwoDot is a registered trademark of Rowman & Littlefield.

Project Editor: Lauren Brancato

Layout: Joanna Beyer

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available on file.

ISBN 978-0-7627-8756-2

eISBN 978-1-4930-1418-7

Printed in the United States of America

For all those accused of crimes they did not commit

Contents

Acknowledgments

The trail used to research this book twisted and turned through countless libraries, newspaper offices, historical societies, museums, sheriffs offices, prisons, and churches. We would like to thank the following people and organizations for their assistance in the preparation of this book:

Carl Hallberg, reference archivist at the Wyoming State Archives;

Duane Shillinger, author and historian in Rawlins, Wyoming;

Carol Reed at the Carbon County Museum Collections;

James E. Schmidt, investigator at the Uinta County Sheriffs Office;

Christopher Blue, outreach assistant at the Union Pacific Railroad Museum;

Lana Wilcox, county clerk and recorder in Evanston, Wyoming;

Lewis L. Gould, author and historian;

Dr. Marie Collins, historian for the Moroni Ewer family;

Rev. John Grabish, Sacred Heart of Jesus Parish in Allentown, Pennsylvania;

the staff at the Davenport Public Library in Davenport, Iowa; and

the South Dakota Archives Department.

A special note of appreciation is offered to Charles F. Seng for the background information he provided on Joseph Seng and to Olive Phelps for providing information about Alta Lloyd.

We are grateful to Barry Williams for his fact-checking expertise and to the editorial staff at Globe Pequot Press for their hard work and dedication.

Finally, we are sincerely indebted to our editor, Erin Turner, for giving us the opportunity to write about this historic happening.

Foreword

According to an article in the April 17, 1912, edition of the Wyoming Tribune, No thrill equals that which comes when a home player sends the ball ringing off his bat safely to the outfield. As the number of bases gained by such a hit increases, so does the excitement mount. When one of those drives wins a game, its maker is a hero.

The American West of the early 1900s was the scene of great change. The transcontinental railroad cut a swath through the country, pulling the population away from the East, bringing progress to and signs of the coming industrial age. Boomtowns were turning into cities; the ways of the West were disappearing and giving way to the inevitable intrusion of change.

But as life became more sophisticated and industrial, a simple and pure game captured the attention of a nation. It would become a national pastime, but in Wyoming in 1910 baseball was an obsession.

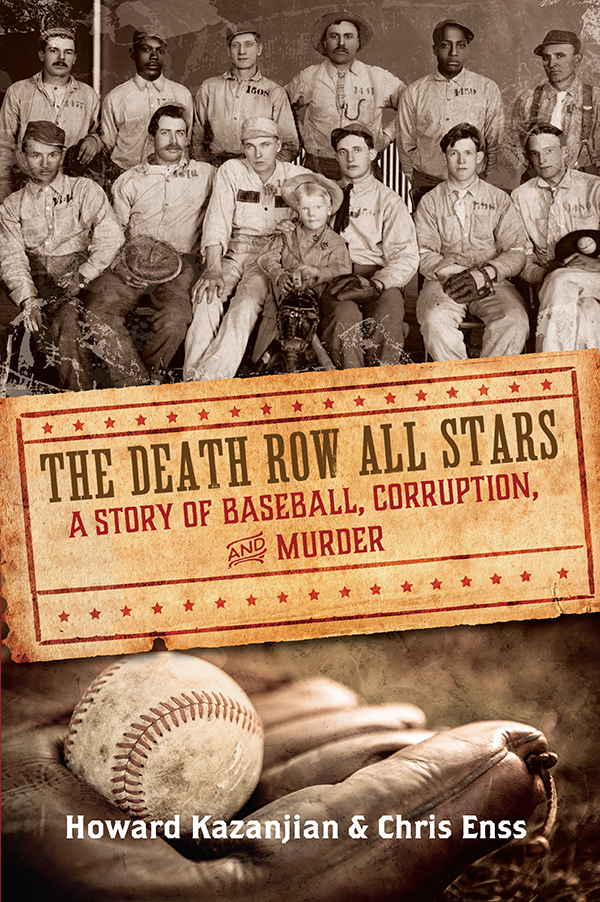

Every town, every camp had leagues or teams of its own. Every team had stars who could easily play alongside Honus Wagner or Ty Cobb. But there were no baseball stars as unique as the Wyoming State Penitentiary Death Row All Stars of Rawlins, Wyoming.

And the star of the All Stars, Joseph Seng.

From the moment he arrived at the penitentiary, Seng was known more for his baseball prowess than his murder conviction. Within moments of his incarceration, prison officials got around to the task of creating a team and building a place to play.

The concept of prison reform and prisoner welfare was nonexistent in 1910. Time on the field was a precious escape from day-to-day life that could be both extremely hellish and (for some) lavishly privileged. Corruption and graft ran rampant. Prisoners were forced to work for little or no wages in the prison broom factory, denied basic necessities, fed rancid food, and forced to work road crews. Others were allowed to openly wander the streets of Rawlins, hunt rabbits outside the prison walls, and reap the monetary windfall of betting on the All Stars.

For the players, baseball was their life, their saving grace. Inside their cell, they were rapists, robbers, burglars, and thieves. But on the playing field, they were fast, hard, and possessed an inside fast ball no one could hit.

Primarily off the strength of Sengs arm (and his bat), the Death Row All Stars quickly became the talk of barrooms, brothels, and even political circles. Fortunes were being made by wagering in exchange for promises of time taken off their sentences and, for Seng, the possibility of a death penalty commutation.

For one cloudless Wyoming summer, residents of Rawlins boasted one of the finest baseball teams in the country. Scores of baseball fans came from all over the state, creating an abstract grandstand fan base. Socialites, merchants, and politicos sat alongside prospectors, ranchers, and drifters cheering for the men in the dark uniforms with W-S-P sewn on their chests.

The All Stars exemplary play wasnt only the talk of the Wyoming territory but was lauded by sportswriters and fans as far away as New York and Boston. Like the western heroes of dime novels, these felon players were indeed all stars.

But Sengs on-field performance failed to afford him great luxuries within the prison walls. For as many that respected and admired his abilities, there were those who resented his perceived celebrity status, making it their lifes work to kill the prison right fielder.

Yet all of this seemingly left Seng unaffected. He was always a quiet gentleman. He spent his time off the field working alongside the prison doctor, writing letters to family and his spiritual advisor, and dreaming of the woman he lovedthe woman whose husbands life he took, putting him behind bars, condemned to death.

On the field, he was alive and would continue to live. Joseph Seng was well aware that as long as the All Stars were on the field and generating money and fame for the prison and the state, he would be guaranteed to live another day. The conspiracy to keep the slugger alive reached from the guards and the warden to local officials and the governor himself.

Sadly, like everything around him, progress would greatly alter Sengs reality. Under the pressure of the growing morality (or guilt) of society, it was decided that the prisons needed to change. In order to save his own political hide, the governor vowed to end the wagering. Reading and writing were deemed more important to reforming prisoners than pitching and batting.

Before they were allowed to finish their inaugural season, the All Stars knew it was over.

Each player went back to his cell, back into his darkness. Some were paroled, some escaped, some died. But each one carried with him the memory of his time on the diamond, in the sunshine. They kept with them the absolute joy of the time in hell when they were allowed to play. They werent playing for the glory, and certainly not for the money. They were playing for the love of the game; they were playing for the freedom.