Copyright 2018 by Todd Radom

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Sports Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Sports Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Sports Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Sports Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.sportspubbooks.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

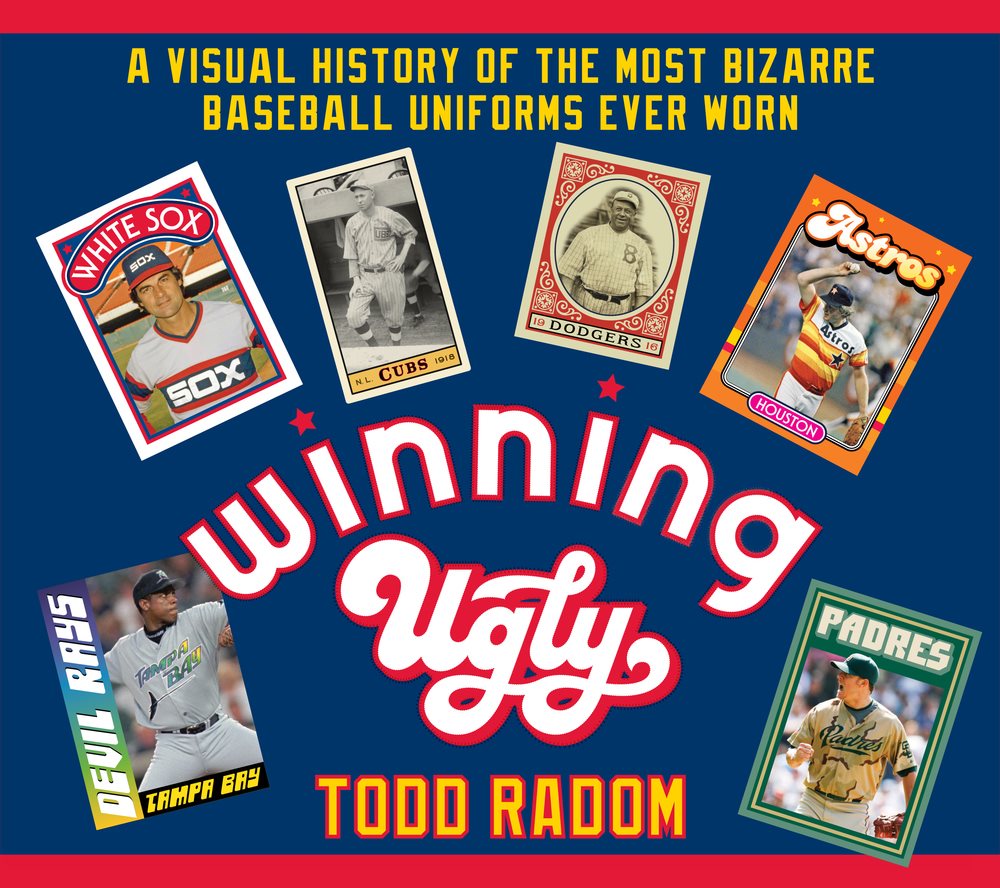

Cover design by Todd Radom

Cover photos: AP Images and the Library of Congress

All photographs, unless otherwise noted, are courtesy of AP Images.

All illustrations are courtesy of the author. All uniform photographs are courtesy of the Bill Henderson collection.

Print ISBN: 978-1-68358-228-1

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-68358-229-8

Printed in China

For Susanne

whose advice was write, then keep writing.

Table of Contents

Introduction

C ooperstown, New York, rightly calls itself Americas perfect village, a point that few could argue. Its picturesque two-block-long Main Street parallels the southern end of Lake Otsego, a serene 7.8-mile-long body of water that writer James Fenimore Cooper accurately dubbed Glimmerglass.

While its apocryphal status as the birthplace of baseball has long been debunked, Cooperstown, of course, plays host to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, which first opened its doors in the summer of 1939.

Every year, hundreds of thousands of visitors enter the Federal-style red brick building at 25 Main Street and immerse themselves in the history of the gamebut only a fortunate few can access its secure, climate-controlled storage area, located deep in the bowels of the facility.

Anyone lucky enough to gain entry to this area comes away with the distinct sense that this would be the ideal place to survive a nuclear attack.

I will omit certain details. There are some mysteries that should remain a secret, but trust me, this is an exceptionally special place.

Walk past the gallery of iconic bronze plaques. Enter a door, head down a flight of steps. There, a long hallway beckons, followed by more heavily protected doors. You sign in. Finally, you enter a room. You then don a pair of white protective gloves.

You are then overcome by an eerily calm sensation, enveloped in a cool chill, accompanied by absolute silence.

The room is, at first glance, impossibly white. The floors and walls are light in color. Tall stacks of archival white boxes loom. Within them reside game-worn examples of some of the most spectacular uniforms in the history of the sport.

Heres a creamy flannel jersey, embellished with wide navy blue pinstripes, worn by some New York Giant player over a century ago. Over there is a thick gray wool number, replete with laces, upon which sits the bold decoration of a red sock with the word Boston within it, an impossibly rare game-worn example from 1908. And here, resting quietly, is another uniform from 1908, worn by a member of the World Series champion Chicago Cubs, featuring a black felt letter C, looped around a dyspeptic-looking bear cub holding a baseball bat.

These jerseys are stunningly beautiful.

This book is not about those jerseys.

Professional baseball teams have been tinkering with their on-field look for a century and a half. Along the way, there have been hits, and there have been misses.

Baseball, more than any other sport, lends itself to introspection and observation. The season is a marathon. It begins in Spring Training in February or March, and it concludes with the final out of the World Series in the final days of October, if not the first week of November.

For many baseball fans, their relationship to their favorite team begins with the uniform. As comedian Jerry Seinfeld famously observed, the players come and go, teams sometimes move from city to city, and fans end up rooting for the clothes.

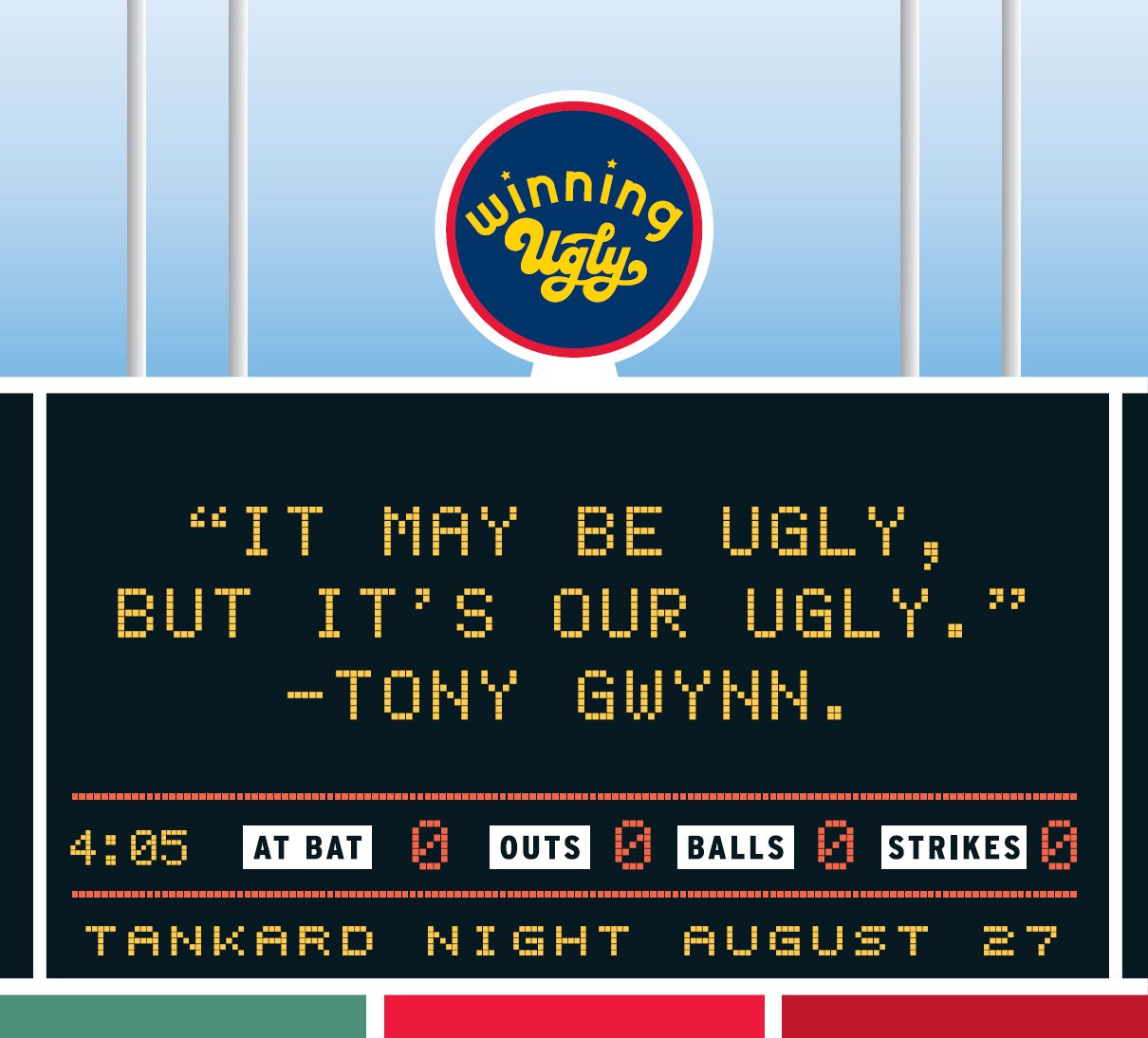

This is a book for those of us who look at those clothes with interest. Sometimes this interest is akin to watching a dumpster erupt in flames, transfixed by whats happening, all the while a little nervous at what the end result might be.

Its a tribute to the sheer chutzpah of whomever it was that decided that the Pittsburgh Pirates should wear a dizzying combination of black and gold uniforms that made them look for all the world like a swarm of bumblebees.

This is for everyone who, like me, knows that once upon a time, the Padres looked like tacos and that the Astros wore tequila sunrises, that the White Sox swathed themselves in leisure suits, and that once upon a time in Cleveland, Boog Powell resembled a giant blood clot.

In todays globalized society, one can purchase and consume the same Big Mac in nearly 120 different countries. Much of America looks alike, and quirky regional differences have largely disappeared. Remember the 1977 film Smokey and the Bandit ? The core plot revolves around a scheme to bootleg four hundred cases of contraband Coors beer, then unavailable east of the Mississippi River, from Colorado to Georgia. Today this seems ridiculous; Coors is ubiquitous, easily obtained just about anywhere.

For all of our political and social differences, we are, at long last, a pretty monolithic society when it comes to our consumer culture, and sports is a key part of that. There are still provincial holdouts to be sure, but there once was a time when the Montreal Expos sure as hell looked like they came from a French-speaking country and when the San Diego Padres gave off a strong whiff of Taco Bell, a Southern California fast-food culinary staple.

These were the halcyon days of pet rocks and Gee Your Hair Smells Terrific, of streakers and of string art. This was a time when our sports graphics and uniforms were more joyful and more spontaneous, before they were mass-produced by behemoth apparel companies whose primary focus is and will always be the almighty, focus-tested bottom line.

I am a child of the seventies, born in the waning days of The Baby Boom. My parents took me to the 1964 New York Worlds Fair in a stroller. Some of my earliest school memories involve watching Apollo moon shots in elementary school on a big black and white television, an event so spectacularly noteworthy that it warranted a temporary halt to the school day.

I was born in New York City and I vividly remember the summer of 1977. That was the Summer of Sam, the summer of the blackout, and the summer that I watched the expansion Toronto Blue Jays and Seattle Mariners, resplendently attired in their powder blue road uniforms, get crushed by the mighty Bombers at Yankee Stadium in the Burning Bronx.

The ticket stubs tell the story. My great-uncle Gus, a resident of Inwood in Upper Manhattan, was an avid New York Giants fan until his team deserted him for the City by the Bay and broke his heart. He then became an avid Mets fan, much to the chagrin of his Yankee-loving wife, Irma. On July 16, 1977, a mere four days after the great blackout, he took me to Shea Stadium to see the Mets play the Pirates on Old Timers Day. I sat in loge section 30, box 474A, Seat 3. The stub depicts a despondent Mr. Met, a single tear trickling down from the right eye of his big round head, hoisting an umbrella: the rain check area of the ticket.

Next page