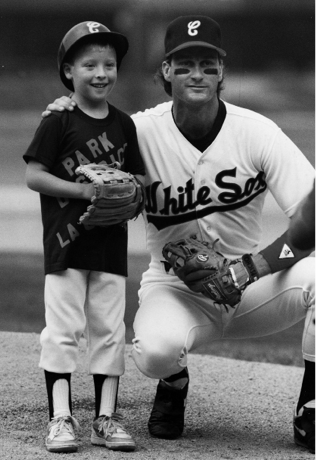

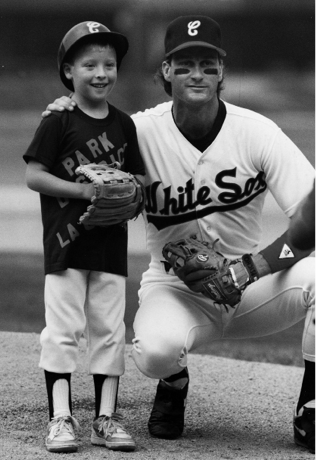

This book is dedicated to my son, Brad, who once was a White Sox fannote the photo of him at age six with Steve Lyons in July 1989, after the ceremonial first pitch. Sadly, though, he long since defected to join fandoms of two teamsthe Oakland As and Toronto Blue Jaysthat invariably make short work of the Sox when they meet, whether its here or on the road.

Not only has he taken great pleasure over the years in the Soxs utter inability to win in Oakland, but at age 10 he came along with me to the Sox-Jays playoff opener wearing a Toronto batting helmet. When Juan Uribe threw to Paul Konerko for the final out of the 2005 World Series, he was saddened at first but then reminded me that the As had gone 72 against the new world champions that season.

My wife and I wonder where we went wrong. Maybe if I had been home at night rather than at work. Well, there is still time for him to come home.

At least he hasnt become a Cub fan.

Contents

Extra Innings!

Introduction

Theyre still the White Sox, and even after 2013s disaster of a season, theyre still our White Sox. But fans should know that, just three years after the Sox finished last in 1948, they were in first place at the All-Star break in 1951; that two years after they lost 106 games in 1970, they were in first place in August; that in 1977, a year after they finished last, they were in first place in August; that in 1990, a year after they finished last, they went 9468; and that in 2008, a year after going 7290, they defeated Minnesota in the Blackout Game to win a division title.

The next thing White Sox fans should know before they begin perusing this book is that the White Sox, since they began playing in New Comiskey Park in 1991, have had totally different ballclubs from the ones that played at the old park across 35 th Street and dealt with a totally different set of meteorological factors. For whatever reason, there is what amounts to a jetstream at what is now called U.S. Cellular Field that helps take batted balls hit toward right-center field on much longer rides than the baseballsand those who batted themhad any right to expect.

This feature first became obvious on the day the new park opened in April 1991, when the Detroit Tigers hit four home runsall by right-handed hitters and two of which seemingly were just high flyballs to right field. Instead of being caught 10 to 15 feet short of the warning track, these balls kept going and going until they nestled in among the surprised bleacherites. Soon the White Sox too found the range and ended up hitting 139 long ones that season74 at New Comiskeycompared to a total of 106 in 1990 (and just 41 at the old park).

And so it was that the White Sox, for years derided as Punch-and-Judy hitters playing in a ballpark that humbled sluggers, suddenly were launching home runsboth at their new long-ball-friendly home park (renamed U.S. Cellular Field, a.k.a. The Cell in 2003) as well as on the road. They hit as many as 216 in the division-title season of 2000after which management decided it would move the bullpens to make them more visible to fans. That, however, meant moving the fences in from 347 feet down the lines to 330 (left) and 335 (right). Later, when the top eight rows of the upper deck were lopped off after the 2003 season to make the climb to the Cells highest seats less foreboding, almost all well-hit baseballsnot just those driven toward right-centerautomatically became home run candidates. (The Sox hit 220 homers in 2003 and 242 in 2004.)

Also, even though head groundskeeper Roger Bossard watched his dad, Gene, create it, Bossards Swamp is a thing of the past, a relic of the 60s, when the muddy home-plate area (and lengthy infield grass) contributed mightily toward making the final score of a Sox game invariably 21 or 32. The White Sox, furthermore, no longer store game balls in a cold, damp and musty storeroom in the bowels of the ballpark. That was another 1960s stratagem designed to ensure that, since the Sox werent going to hit home runs, their opponents wouldnt hit any either. So, whereas the Sox club leader in home runs might have hit 15 to 19 in a season during the 1940s, 50s, and 60s, for example, and 25 to 30 during the 70s, nowadays theyre routinely hitting 40 and more.

These White Sox, then, are not your grandfathers White Sox. The hallmarks of many of those clubs were pitching, speed, and defense, key ingredients all for success at old Comiskey. The Go-Go Sox hit doubles and triples and ran the bases with abandon, then depended on defense and solid pitching to keep opponents at bay. In this new era, the Sox all too often have played station-to-station ball and depended on the home run200-plus per season. Used to be that the Sox might hit a home run every other game. Lately it seems like one every other inning.

It will soon become apparent, then, that most of the franchises big offensive numbers have been recorded since the move to the new ballpark in 1991. Call them the A Sox (1901 through 1990) and the B Sox (1991 through the present), if you wish. But there is a difference. A big difference.

Maybe someday theyll be the C Sox, champions once again. While youre waiting, flip through these pages and read about pennant races and roof shots, legendary players and some not so legendary, stories of cheating scoreboards, oversleeping outfielders, and the biggest home run in club history. Learn about Fox and learn about The Fix, the glory days and the gory days, the Blackout Game and the White Flag trade. The story of the youngest pitcher to ever start a major league game, and the outfield prospect who at 19 clubbed two homers at Yankee Stadium in the 1962 season finale and, three years later, was out of baseball entirely, having launched a career in art. (The chapter is entitledwith apologies to James JoycePortrait of the Artist as a Young Outfielder.)

And my apologies to Mike Joyce, former Sox right-hander, a longtime resident of Wheaton, Illinois, and a grand guy, for my referencing James Joyce in a White Sox book and not him!

1. 88 Was Enough

The scene on the field at Houstons Minute Maid Park was almost unimaginable. This wasnt really happening, was it? Men in Chicago White Sox uniforms were jumping on top of each other, hugging each other, celebrating something that the franchise had not accomplished in 88 years: the winning of a World Series. For the first time since 1917, the White Sox our White Sox were world champions, having swept the Houston Astros in four straight games.

Stop and think of how long ago 1917 was. It was so long ago that Chicago had a Republican mayor, Big Bill Thompson. It was the year the U.S. declared war on Germany and sent its boys to France to fight the first of the centurys two world wars. It was the year the National Hockey League was formed, with just four teams: one each from Toronto and Ottawa, two from Montreal, and none from Chicago.

Since their 1917 World Series triumph over the New York Giants, the White Sox had won American League titles in 1919 and 1959 and division championships in 1983, 1993, and 2000. There could have beenindeed, should have beenmore successes along the way to this glorious 2005 postseason, which had ended just moments earlier on the second of two sensational ninth-inning plays by shortstop Juan Uribe. But now, in these moments, previous failures were forgotten. In this 2005 World Seriesand also in the two postseason series that preceded itthe Sox were the ones who had delivered the big hit, like Jermaine Dyes eighth-inning, two-out RBI single to center that provided the lone run of Game 4.