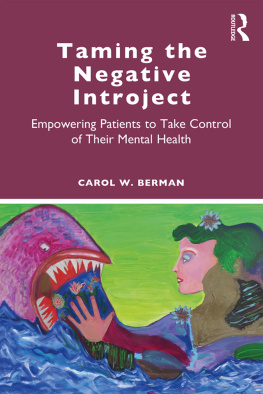

Houseboat on the Ganges

&

A Room in Kathmandu

Letters from India & Nepal 1966-1972

Marilyn Stablein

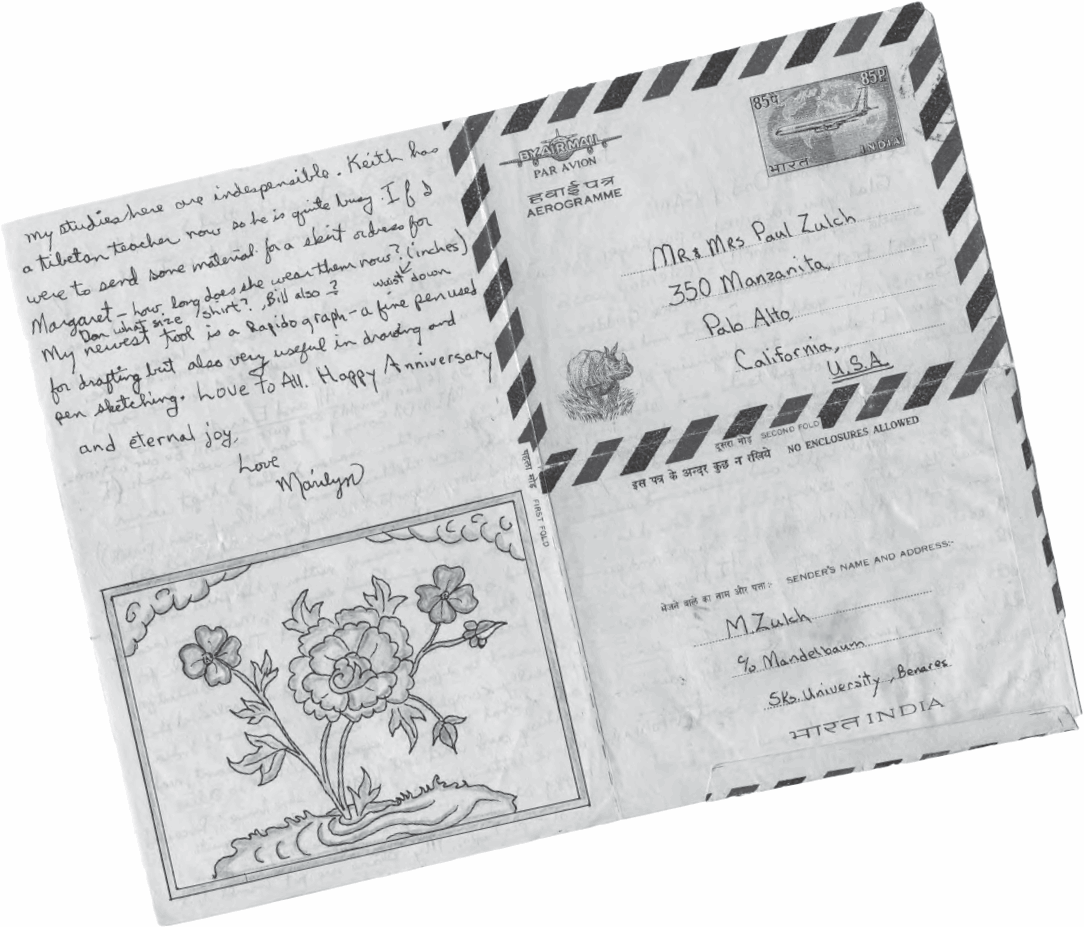

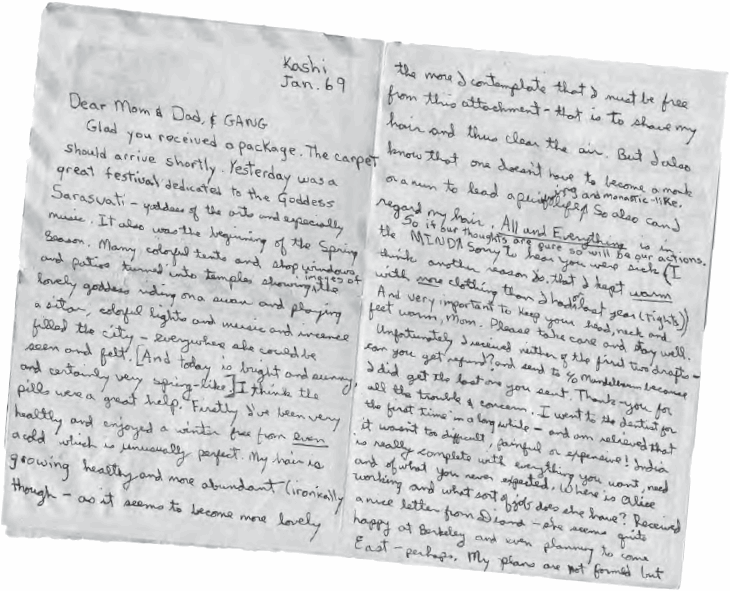

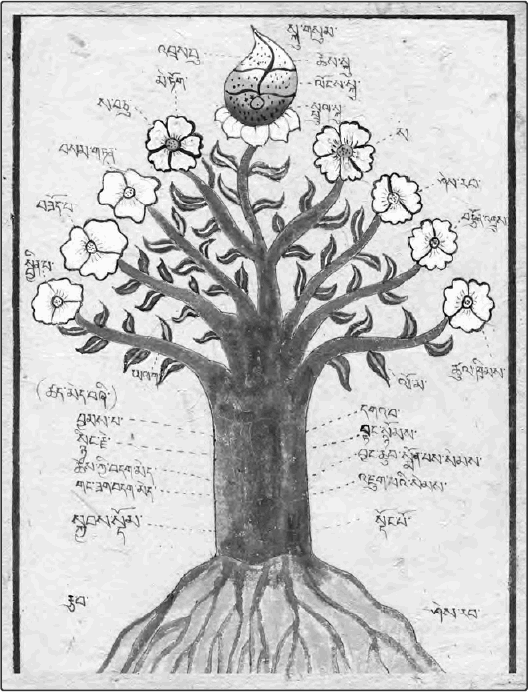

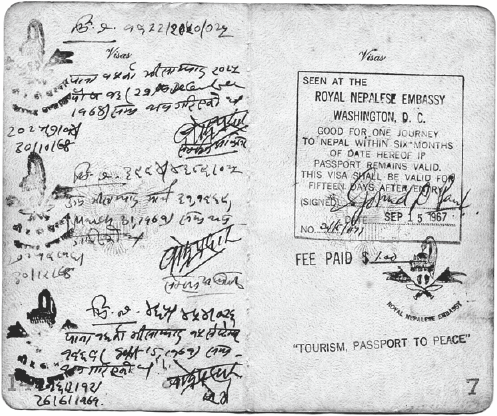

All of the photographs, collage illustrations and ephemera are either by Marilyn Stablein or from the artists collection.

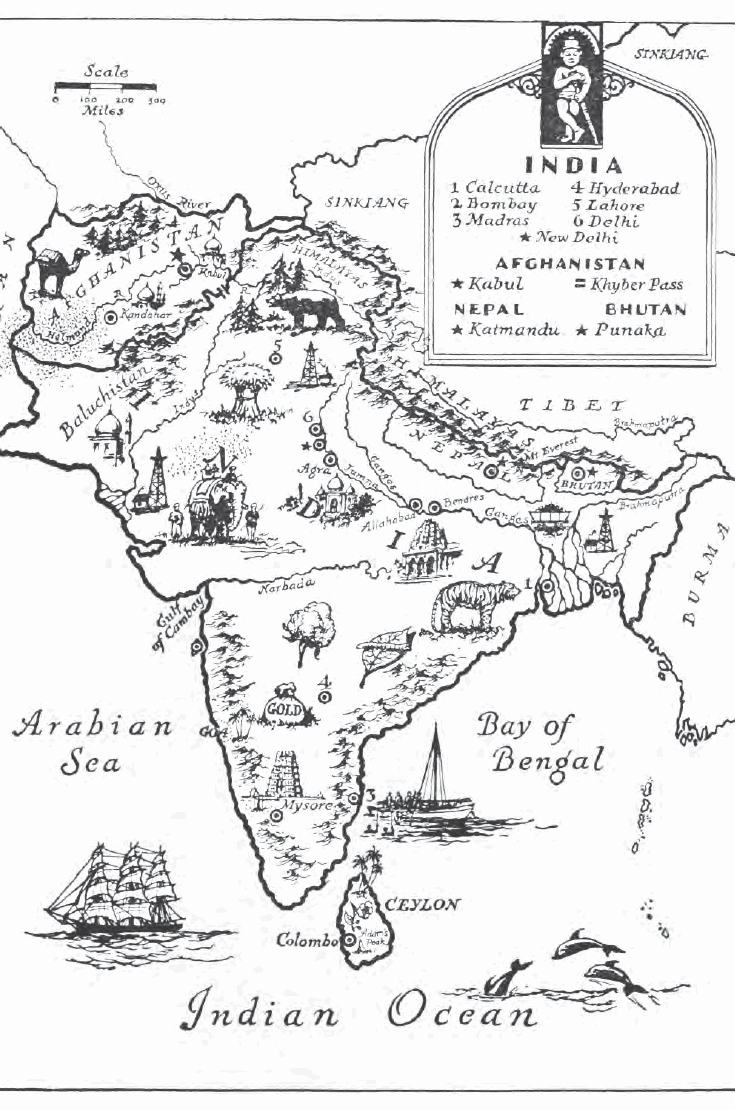

The text of Houseboat on the Ganges & A Room in Kathmandu retains a few of the anglicized names for cities like Benares (Hindi, Varanasi) and Bombay (Hindi, Mumbai) since they were the most commonly used place names in books and tourist brochures as well as signs at railway stations and shops in the sixties.

Copyright 2019

By Marilyn Stablein

Published by:

Chin Music Press

1501 Pike Place #329

Seattle, WA 98101

www.chinmusicpress.com

All rights reserved

First (1) edition

Cover art & photographs by Marilyn Stablein

Book design by Carla Girard

ISBN978-1-63405-972-5

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data is available.

Every day is a journey, and the journey itself home.

Matsuo Basho

Narrow Road to the Deep North

In memory of my father Paul Zulch and especially my mother, Thelma H. Zulch, who encouraged me to follow my curiosity and then received, read, and saved my letters for seven years. With love and gratitude.

Houseboat on the Ganges

&

A Room in Kathmandu

Letters from India & Nepal 1966-1972

CONTENTS

PREFACE

A Note on the Letters

Half a century ago, before internet travel reservations, access to online listings and reviews of hotels, restaurants, train, bus, and ferry schedules; before online maps of historic sites and attractions; before internet banking, e-mail, cell phones, skype, scanners, and faxes, I left home at eighteen, my only belongings crammed into a dusty backpack, to hitchhike from Istanbul overland to India after a year of travels in North Africa, Europe, and England.

I was curious about Asia growing up in the far West between the foothills of the Santa Cruz mountains and the San Francisco Bay. On family trips to Half Moon Bay I loved watching the sun turn a tangerine gold before slowing sinking into the great exotic, pulsing, and restless Pacific Ocean. Staring out into the blue expanse and limitless sky my imagination swelled with a host of storybook and cinematic images gleaned from my growing awareness of the mysterious lands beyond the ocean. Later Id learn how the Pacific Rim countries and states including California, Oregon and Washington, were connected in a vast global community spread out over twenty thousand miles of shared shoreline.

I felt at home in San Franciscos Chinatown where I shopped for inexpensive hand-painted paper fans and Chinese paper lanterns. I wandered the aisles of Cost Plus in Palo Alto and found Christmas presents for my family. Japan was the source of cheap and exotic toys and knick-knacks after the war. I noticed porcelain trinkets like salt shakers and ceramic dogs and cats stamped at the bottom: Made in Occupied Japan. I wore tabis, those black cotton slippers with openings next to the big toes so my cloth-covered feet could easily slip into oriental thong sandals or summer flip-flops.

One Christmas my father gave me a book of Chinese fairy tales. Id fall asleep envisioning jade princesses and the ghosts who haunted the dark footpaths through Chinese forests. Stone or metal Buddha statues, pagoda temples and palaces, reverberating temple gongs, Chinese junks and jade necklaces all sprang to life in crazy travel fantasies. More than once I daydreamed about the blue willow dishes we ate dinner onthe lovers separated by a circular foot-bridge like the one I awkwardly climbed up and over on school field trips to the Japanese Tea Garden in San Franciscos Golden Gate Park.

On game nights around the dining room table, father taught us to play Parcheesi, a game that originated in Indiathe name derives from the Sanskrit panca, five, and vimsati, twenty, referring to twenty-five, the highest throw. My favorite game was World Traveler with the unfolding game board map of the worlds oceans and continents. Players traveled jump by jump to every exotic corner of the world. The first to circle the globe won.

When I visited a school chum of Japanese descent, a gold Buddha with heavy eyelids serenely graced a sideboard in the living room. At the entry to a Chinese friends home, a figurine of the Goddess of Mercy Kwan Yin rose gracefully above a bowl of incense ash in an alcove by the front door.

I biked everywhere, thrilled with the freedom to explore neighborhoods on my own. One day as I bicycled down Middlefield Road in Palo Alto, I noticed a sign for a Buddhist temple. Curious, I parked my bike and went to investigate. A Japanese caretaker kindly showed me the Buddha statue on an altar decorated with flowers and plants. Later I asked my mother to drive me back for a spring Bonsai plant sale.

A Japanese Zen priest, Suzuki Roshi, helped popularize Buddhism and Zen meditation. Alan Watts, an English Zen Buddhist scholar, who lived on a houseboat in Sausalito, California first linked Zen with the Beats in his essay, Beat Zen, Square Zen and Zen. His The Art of Zen lectures, which regularly aired on Pacifica radio KPFA, sparked my interest as did the work of Paul Reps, one of the first American haiku poets to write about his travels and studies in China and Japan beginning in the 1940s. His books Zen Telegrams and Zen Flesh, Zen Bones, were bestselling mass market paperback titles.

Japanese programs frequently appeared on educational television. Every Tuesday evening, I reserved an hour (no small feat in a family of eight) to follow along with T. Mikami, a Japanese brush painting master, on his channel 9, KQED art show. He first introduced me to sumi ink brush paintings of Mt. Fuji, pine cones, lobsters, and fish.

I checked out books on haiku from the Palo Alto Public Library. The travels of the wandering ascetic Siddhartha

CONTENTS

CONTENTS