Fiction by Kief Hillsbery

WAR BOY

WHAT WE DO IS SECRET

ONCE AGAIN

to David

What I mean is, that if I had some more detective stories instead of

Thucydides and some bottles of claret instead of tepid whisky,

I should probably settle here for good.

ROBERT BYRON , The Road to Oxiana

CONTENTS

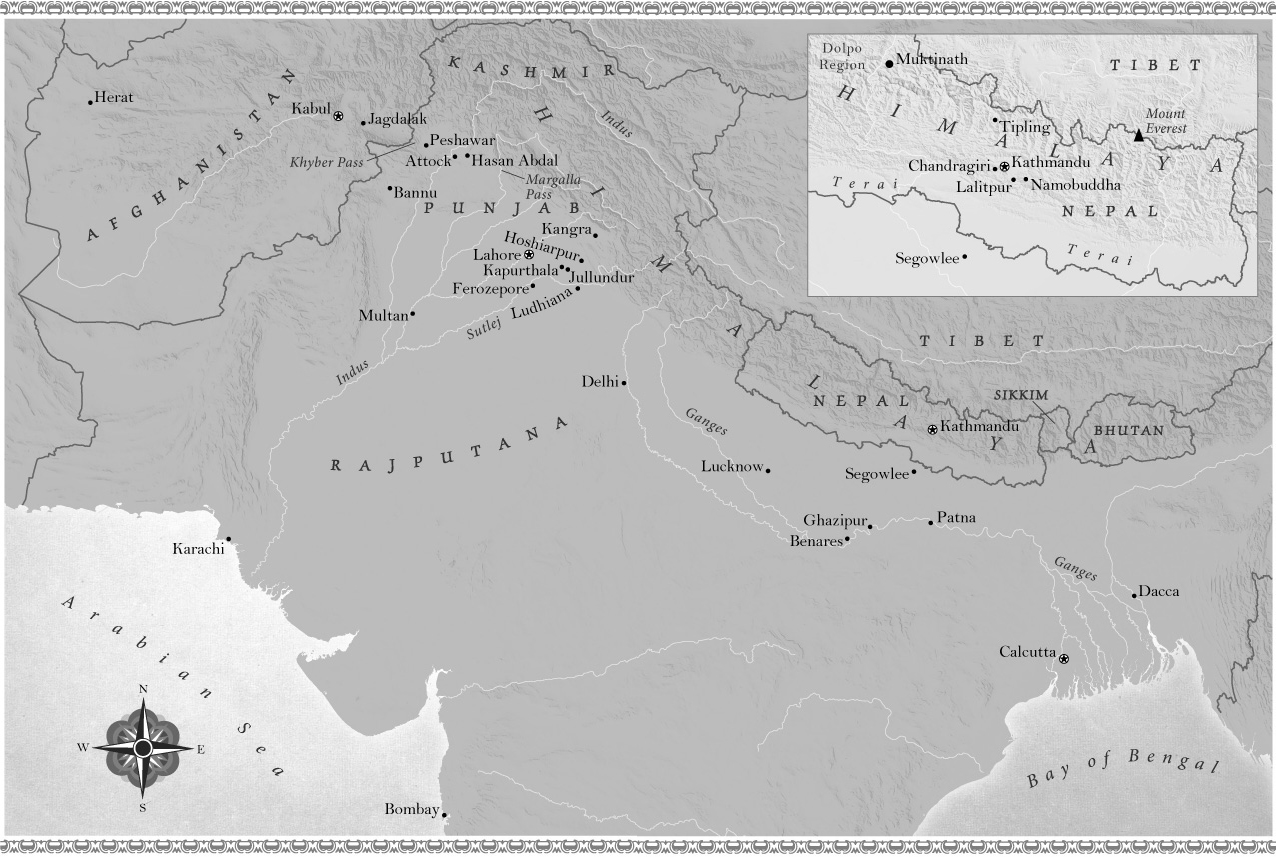

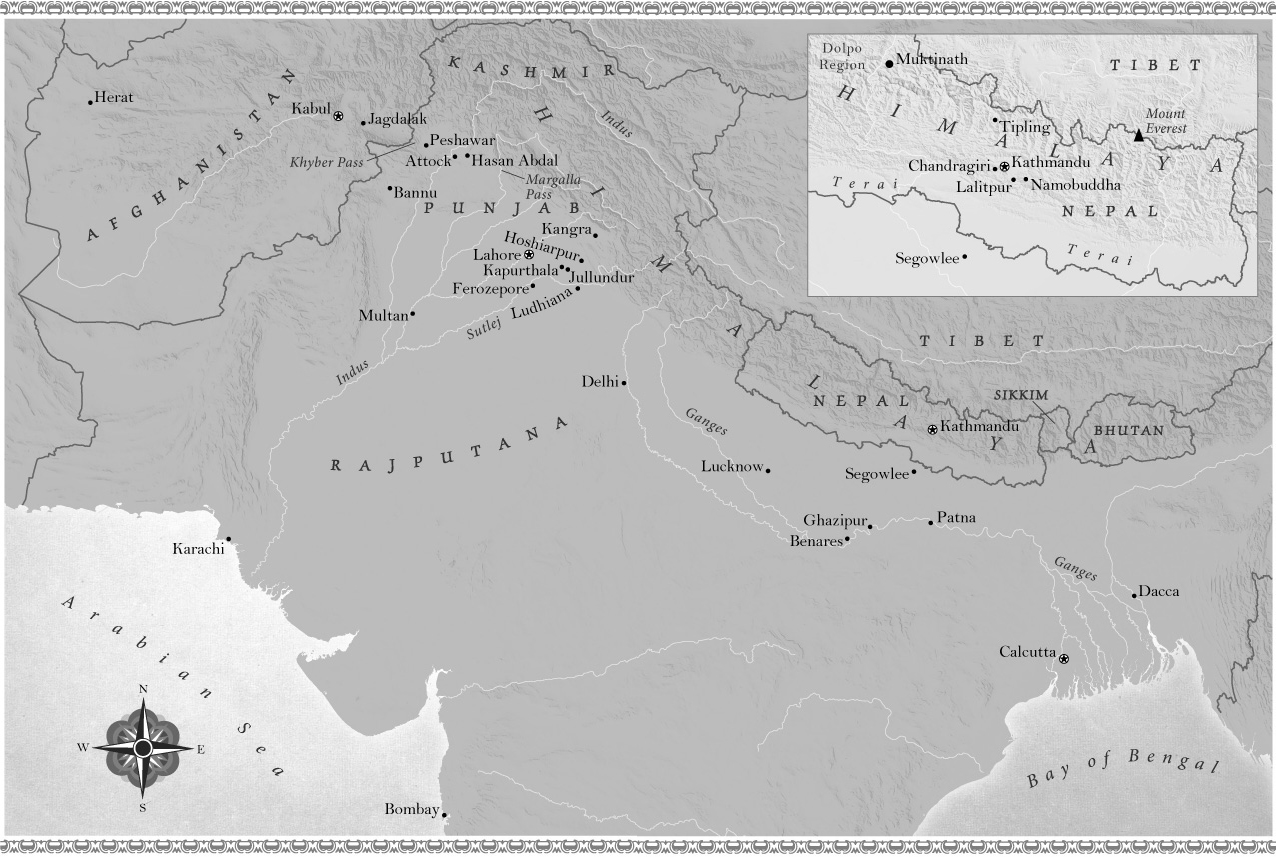

Nigel Hallecks India, 1845

Prologue

T HIS BOOK TELLS the storyoften shadowy, sometimes perplexing, frequently eccentricof an English gentleman who went out to India in the era of Kiplings white mans burden and found that its weight was more than he could bear. Like his ten thousand countrymen who dispensed justice and imposed taxes on one-fifth of the worlds population in the 1840s, he was neither a civil servant nor a soldier, but a salaried employee of a joint stock company whose shares were traded on the London exchange. It is the strangest of all governments, said the Whig politician Thomas Macaulay in the House of Commons in 1833, but it is designed for the strangest of all empires.

For the first two hundred years of the Honourable East India Companys existence after its charter by Elizabeth I in 1600, its men on the ground in India fit the mould of ruffians and buccaneers more than rulers. But powerful forces back home eventually worked to refine the behaviour of Company employees and transform the role of the Company itself. The first was the rise of the Evangelical movement within the Church of England. Until 1813, missionary work was against the law in colonial India, on grounds that it caused disaffection among the natives and undermined British political authority. But when the Companys charter came up for renewal that year, it was obliged by Parliament to welcome missionaries as the price of retaining its trading privileges.

The second was the propagation of Jeremy Benthams philosophy of utilitarianism, which held that moral, social, and political action should be directed toward achieving the greatest good for the largest number of people. The idea that Indians were a backward race who should be ruled by Englishmen for their own good replaced the profit motive as the engine of colonial administration. By the time a wide-eyed twenty-year-old named Nigel Halleck debarked from a packet steamer onto the teeming docks of Calcutta in 1842, the East India Company was no longer involved in commerce at all. Its mission was to civilize, and Christianize.

Nigel was my mothers grandfathers great-uncle. The first time I heard of him I was a child, on a visit to my aunts home in the old market town of Coventry. On the rainy afternoon of a grey day, I sat on the floor of her dressing closet and watched my sister bedeck herself with cast-off jewellery, culled from heirlooms my aunt thought too hideous to wear but too ancient to discard. I rummaged through her leavings and held up a heavy silver brooch, black with tarnish. It was particularly old and particularly ugly. The shield was fussily chased, and the large, gaudy stone gleamed pink as candy floss.

Its facets caught the light from the dim bare bulb overhead and sparked with lurid fire. I turned the brooch in my hands and read out the spidery text engraved on the back:

Your loving Nigel

Who was Nigel? I asked my aunt.

That would be my uncle, she said, many times removed. He had gone out to India.

I asked why.

To help those poor people, she said. Many men did in those days.

India, she explained, had figured in the lives of several of my ancestors. A consulship in Burma was mentioned, and there had been a couple of vicars, and someone in railway administrationno, not an engineer, of either sort. Driving a train, she informed me, was common, and as for devising a railways routegrades and bridges, tunnels, beds for tracka head for such figures never sat on the shoulders of anyone who bled our blood, she was absolutely sure of that.

How long were they in India, I wondered, and what was it they did afterwards, back in England, and after she told metwo or three years for the consul and the clergymen, five she supposed for the railwayman, and more or less the same as what they did in India, practised their professionsI returned to Uncle Nigel: what did he do?

Do?

In England. After India.

Actually, she said, he never came back. He stayed in the East.

His whole life?

Indeed he did.

He must have liked it.

I suppose he must.

Was he the only one ever? Who stayed?

Heavens, no. Many have. Why, Mother Teresa

In our family.

No others came to mind, she said. Not for India. There was my mother, of course, who married my American father after the war and decamped across the pond.

Did Nigel get married? Was that why? To an Indian?

Certainly not. Of course not.

He never had a wife?

Im afraid not.

The brooch had been a gift to his mother, she said.

Then she changed the subject, leaving me with both a clear sense that she disapproved of Nigel and the vague notion that there was more to his story than my aunt thought suitable for sharing with my ten-year-old self. A decade later, when I was on the verge of heading East myself for a college year abroad in Nepal, my mother confirmed my suspicions. Nigel, she confided, had separated from the East India Company under some sort of cloud. Afterwards he had supposedly gone native in Nepal and lived until his death in 1878 as one of a handful of Europeans admitted to the then-forbidden Himalayan kingdom.

According to family legend, his exile was forcedhe couldnt stay in India or come back to England. But no one quite knew why. He might have been a jewel thief, he might have been a spy. He was, everyone agreed, a hunter of big game, and one story had it that he met his end in the mouth of a man-eating tiger in the Terai jungle, on the border of Nepal and India.

My mother was less troubled by the manner of his reputed demise than by its loneliness. On the eve of my departure in the spring of 1975, she entrusted me with a sheaf of pages from letters written by Nigel in the 1840s and early 1850s. Some were reproduced on vintage copy paper, slick and vaguely toxic. Others were transcribed from the originals. Only a few of the letters were complete. She said that most of his correspondence had been lost in the Nazi bombing of Coventry, as had the whereabouts of his grave. To her way of thinking, it was nothing short of scandalous that in all those years none of Nigels relativesnot even those who spent years in India themselveshad ever had the bottle to find his gravesite and pay their respects.

I promised I would do my best to be the first. I had never been to Asia. I thought it would be simplean enquiry here, a walk through a graveyard there. I had no idea that the very concept of bureaucracy was invented by the Mughal rulers of India in the fifteenth century, only to be raised to impenetrable perfection by the British who supplanted them as imperial masters.

TWENTY-ONE YEARS LATER, nursing a glass of sweet milky tea in a caf in Kathmandu, at the end of my third sojourn in Nepal, I had so far succeeded only in prolonging the scandal. By 1996 I had traipsed across a half dozen colonial cemeteries, forgotten ossuaries of empire where epitaphs alluded to epidemics, massacres, and the shimmer of moonlight upon the freshet Clyde. I had come to navigate the stacks of several British Council libraries with the same hard-won sureness I felt after mastering the subway maze beneath Times Square. I had devoted time and trouble to near-forensic examination of vermin-chewed ledgers in the archives of the family that had long ruled Nepal, and more conversations than I could count with persons and personages in India, Nepal, and Pakistan deemed likely to know where all manner of bodies were buried. For more than half my life, I had tried and failed to find out exactly what became of Nigel Halleck.

Next page