NICHOLAS B. DIRKS

vii

ix

xix

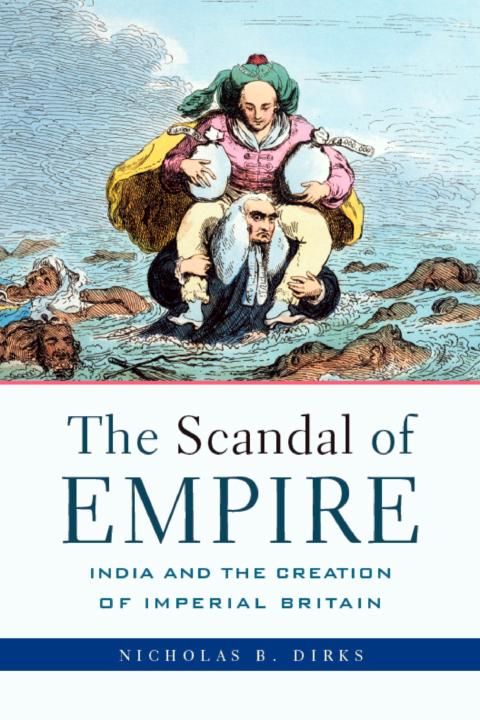

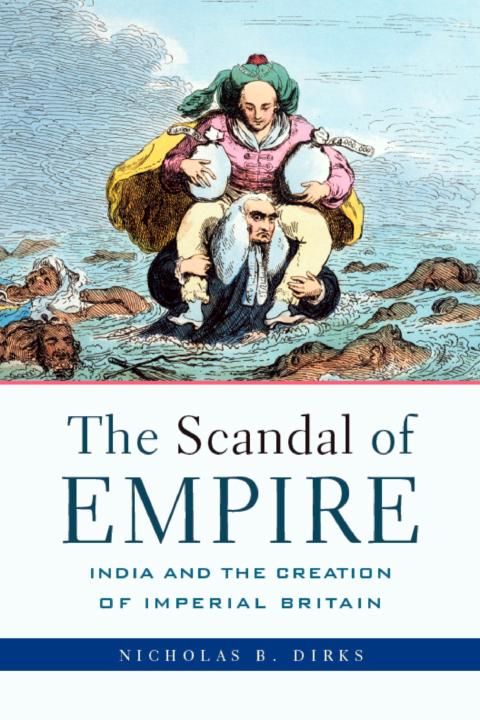

A 1788 caricature showing Edmund Burke about to hang Warren Hastings facing page 7

Lord Clive, under examination by a committee of the House of Commons facing page 37

Opening day of the impeachment trial of Warren Hastings facing page 87

Warren Hastings, mounted and attired facing page 133

Warren Hastings painted in Mughal style facing page 167

Lord Clive meeting Mir Jafar on the battlefield of Plassey facing page 209

Portrait of the nawab of Arcot, Muhammad All Khan facing page 245

Portrait of Edmund Burke facing page 285

Portrait of Warren Hastings facing page 313

As a historian of India, principally southern India, with interests in matters ranging from political sovereignty to caste society, and from precolonial state processes to the British colonial state, how did I come to write a book about Edmund Burke and Warren Hastings? The spectacular impeachment trial of Hastings is a natural subject for any historian of India or empire. Indeed, it has been much written about. Historians of India have explored the meanings and larger contexts of the various events featured in the trial; imperial historians have investigated the political contexts for the trial in England as well as for the history of the East India Company; and literary critics along with cultural historians have used the trial to think about some of the larger implications of early colonial rule-its anxieties and ambivalences, as well as its significance for the unfolding of the gendered, racial, cultural, and national entailments of early empire. What more could I contribute to the discussion?

Significantly, I began thinking seriously about the trial during the years when President Clinton was impeached. The impeachment of Hastings had been the second last use of impeachment provisions in England, though there had been talk of impeaching Hastingss associate, Elijah Impey, who was the first supreme court justice in India and the man who had condemned Hastingss nemesis, Nanda Kumar, to death by hanging in 1775. The last impeachment also had India connections; in 18o6 Henry Dundas, who had been for years the most powerful dispenser of patronage in his position as member and then president of the board of control for the Company, was brought up for impeachment on grounds of corruption. But in the United States, impeachment took on a more modern career, with (unsuccessful) prosecutions of Andrew Jackson and Bill Clinton, and preliminary charges against Richard Nixon around the Watergate break-in and cover-up. In the last decades of the twentieth century, impeachment has provided some of the great moral spectacles of our time, and allowed us to see in dramatic ways the peculiar relationships that have grown up around, and in recent years changed significantly, political ethics, public responsibility, and private virtue. The impeachment trial of Warren Hastings takes on special interest in this context.

But if I came to consider writing about the impeachment trial in the wake of the massive effort to bring down a relatively progressive President-an effort that failed to impeach but succeeded in distracting attention from many of Clintons domestic policy agendas while probably bringing Bush to the presidency-the urgency of rethinking the origins of British empire increased dramatically after I had begun the project. I spent a year of sabbatical leave in 20002001 reading the transcripts of the trial, consulting archival collections in the British Library, and reading works of and about Edmund Burke, only to return to my teaching duties in New York a week before September 11, 2001. Soon thereafter, the U.S. administration began to use the terrible events of that day to provide an alibi to attack Iraq and establish what increasingly looked like, and even came to be popularly described as, an American imperial presence in the Gulf. The use of the charge of weapons of mass destruction as the false pretext for the invasion, the direct economic interests of many of the masters of war, the atrocities associated with the invasion and the occupation as well as with the internment facility in Abu Ghraib, all began to look very similar to an earlier period of imperial history, that of the British conquest and occupation of India in the eighteenth century. As I thought about the various historical parallels, I realized how important it was to revisit the most scandalous origins of imperial history in Britain. And I realized that the impeachment trial of Hastings, far from being the moment when scandal was genuinely expunged from the imperial record, played a much more complicated role in the history of empire. As I continued to research and write, I felt I was writing the history not just of the eighteenth century, but of the present as well. Never has the history of the eighteenth century seemed so self-evidently relevant.

Next page