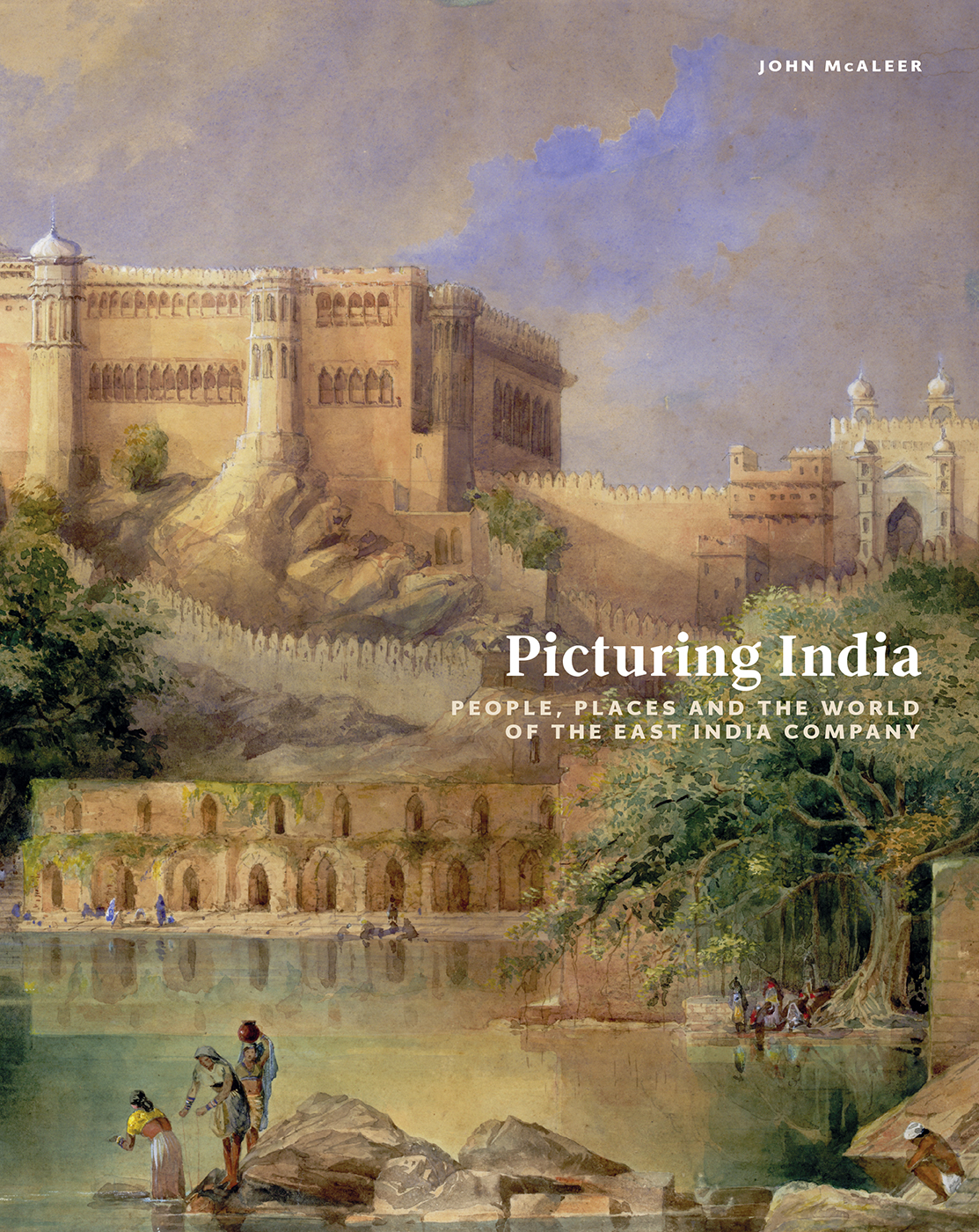

Picturing India

JOHN McALEER

Picturing India

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS SEATTLE

PEOPLE, PLACES AND THE WORLD

OF THE EAST INDIA COMPANY

Picturing India: People, Places and the World of the East India Company

John McAleer

Published in the United States of America by

University of Washington Press

www.washington.edu/uwpress

ISBN 9780295742939

Text copyright John McAleer 2017

All illustrations copyright The British Library Board

except where stated in the captions.

Designed by Maggi Smith, Sixism

Printed in China by C & C Offset Printing Co.

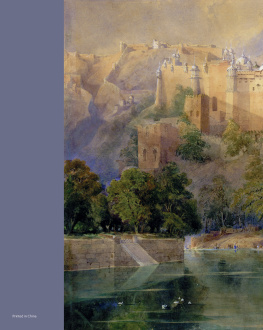

On the jacket: William Simpson, The Palace at Amber, c. 1861 (see )

Pages

All images are from the collection of the British Library unless stated otherwise in the captions. YCBA is the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven.

Contents

Acknowledgements

This book owes its existence to Rebecca Nuotio and Rob Davies at the British Library. Without their interest and enthusiasm for this project at the outset, and their unfailing encouragement along the way, a throwaway comment made during a conversation in one of the Librarys cafes would have remained just that.

During the course of writing this book, I benefited from the help and assistance of a variety of libraries, librarians and archivists. I am grateful to Nick Graffy at the Hartley Library and to his colleagues in the Inter-library Loan Department at the University of Southampton. I would also like to thank Penny Brook, Margaret Makepeace and all of their colleagues in the India Office Records at the British Library for their generous assistance and guidance. I am particularly grateful to Mark Pomeroy and his colleagues at the Royal Academy, London, for permission to consult and quote from the papers of Ozias Humphry. Finally, as ever, I relied heavily on the staffs of the British Library, London, and the Hartley Library at the University of Southampton.

As always, I am grateful to those friends and colleagues who have helped me to think about the East India Company and the images it inspired over the years: Tim Barringer, Robert Blyth, Huw Bowen, Quintin Colville, James Davey, Douglas Fordham, Gillian Forrester, Douglas Hamilton, Sarah Longair, Philip McEvansoneya, John MacKenzie, Margaret Makepeace, Peter (P. J.) Marshall, John Oldfield, Katherine Prior, Geoff Quilley, Johanna Roethe and Zo White. Many of them read drafts of chapters or listened to papers. I am grateful for their help and advice, although naturally any errors or omissions are mine. Thanks in particular to Johanna who read drafts of all the chapters with great insightfulness and unfailing cheerfulness.

This book is about the images. Although the shortcomings and inadequacies of the text are my sole responsibility, the book is the product of significant amounts of collective effort and dedication. I am grateful to Sally Nicholls for her help in sourcing the images. On behalf of everyone who admires the high-quality illustrations, I would like to acknowledge and thank everybody in the Imaging Services department at the British Library who ensured that the images are the real stars of the book. I am also very grateful to Jacqueline Harvey for her careful reading of the text and to the books designer, Maggi Smith, for turning an idea into reality. Where I have quoted directly from a source, the endnotes provide specific references. Readers who are interested in pursuing some of the themes explored in these pages will find suggestions for further reading at the end of the book.

Detail of Figure 1.4 Thomas Daniell and William Daniell, Calcutta from the River Hooghly: Gentoo Buildings, Views of Calcutta, 8, 1788

INTRODUCTION

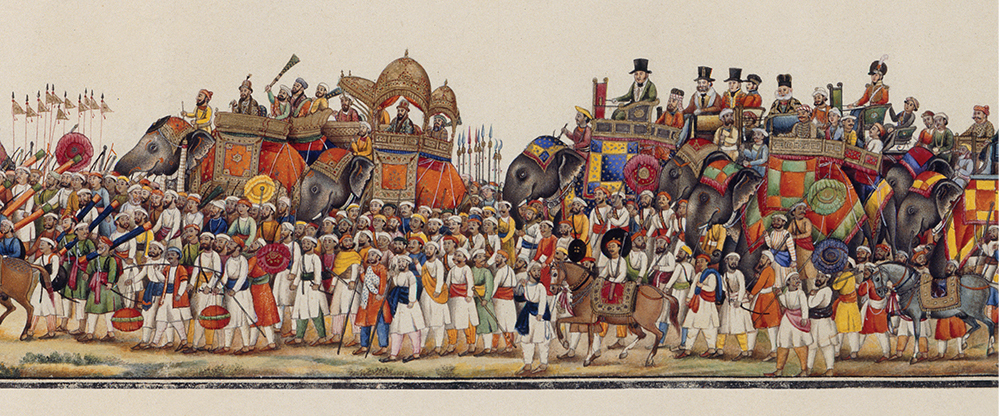

The East India Company and British Views of India

Eighteenth-century India was the theatre of scenes highly important to Britain.).

In matters of trade and war, the Indian subcontinent had assumed an increasingly important role in British political and economic life in the second half of the eighteenth century. This relationship between Britain and India was complex and had its roots in the activities of a London-based trading company. The Company of Merchants of London, trading to the East Indies usually abbreviated as the East India Company controlled British trade with Asia from its foundation in 1600 until the nineteenth century, and was once described as the wealthiest and most powerful commercial corporation of ancient or modern times. Any examination of Britains relationship with India must take account of this extraordinary organisation. By the time Hodges was working, the Company had become a powerful economic and political player there. And its influence was felt not just in Asia. The Companys commercial, political and military activities altered the way politicians and merchants in Britain thought about the wider world. Ultimately, it helped to lay the foundations of the British Raj. If the American colonies and Caribbean islands had once captured the British imagination, the commercial possibilities offered by the Indian subcontinent increasingly occupied British politicians, merchants and travellers as the eighteenth century neared its end.

But the intimate connection, as Hodges termed it, between India and Britain was not just a commercial or political one. It was also an intensely visual one. The historian P. J. Marshall reminds us that the British encounter with India was prolonged and intense, and that it was concerned with cultural exchange as well as commercial endeavour and exploitation:

Even by 1800, thousands of Englishmen had been to India, a huge flow of trade had developed (including the import of artefacts of high artistic quality), many books about India had been published in Britain and visual representations of India and Indians were being widely reproduced.

James Rennells much reprinted Memoir of a Map of Hindoostan, which first appeared in 1783, offers visual evidence of this ( Indeed, these artists helped to document and celebrate the richness and sophistication of Indian culture that later nineteenth-century views often denied. Artists contributed to the work of intellectual engagement with India, offering a parallel to activities in other disciplines such as cartography, comparative linguistics and topographical surveying. Like other European travellers and commentators, the British artists who depicted India in the period took their own expectations, preconceptions and prejudices with them, based on their artistic training, popular notions of taste and the prevailing political sentiments in Europe. Nevertheless these images, produced in the late eighteenth-century heyday of the East India Company, reflect its significance and the impact of its activities on Indians and Britons alike.

Figure 1.1 William Hodges, A View of the Fort of Agra,