Fiona MacCarthy - Gropius

Here you can read online Fiona MacCarthy - Gropius full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Harvard University Press, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Gropius

- Author:

- Publisher:Harvard University Press

- Genre:

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Gropius: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Gropius" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Gropius — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Gropius" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

FIONA MacCARTHY

The Man Who Built

the Bauhaus

The Belknap Press of

Harvard University Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

2019

First published in 2019

by Faber & Faber Limited as Walter Gropius: Visitionary Founder of the Bauhaus

Bloomsbury House

United Kingdom

Fiona MacCarthy, 2019

All rights reserved

Typeset by Faber & Faber Limited

Printed in the United States of America

First Harvard University Press edition, 2019

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication

data is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-674-73785-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

To Richard Calvocoressi

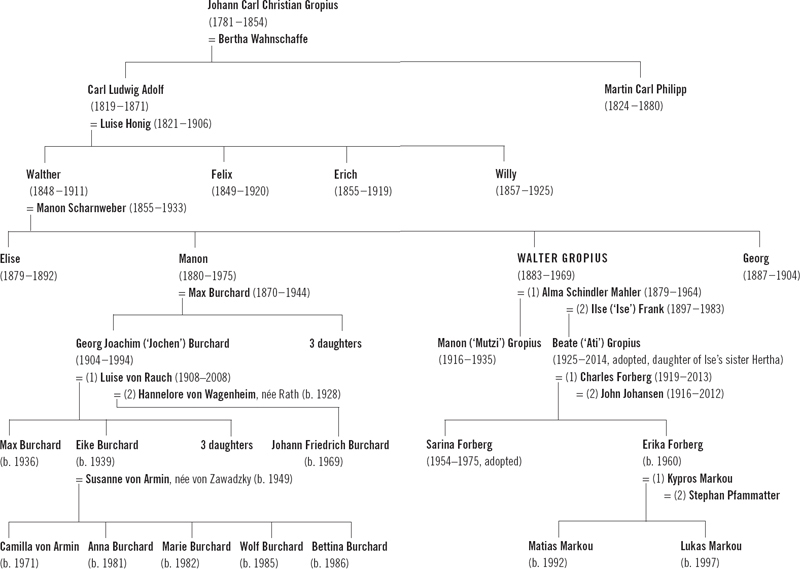

How do you decide on your subject? This is a question people like to put to writers at literary festivals. I tend to answer that my subjects have always chosen me, the result of a long obsession, as with Byron, the fruits of a chance encounter, as with Eric Gill. They sit there in your mind, sometimes for years, waiting to claim you, like the start of a close friendship or inevitable love affair. In fact the starting point of my search for Walter Gropius was not an encounter with a person but a chair.

It was 1964. I was then a mini-skirted Courrges-booted young journalist working for the Guardian. The place was Dunns of Bromley, a modern-minded furniture store in a London suburb. The chair was the Isokon Long Chair. It was not designed by Gropius himself but by his close Bauhaus colleague Marcel Breuer and it was created when they were both living in England, taking refuge from the Nazi regime in Germany. I may have been the Guardians Design Correspondent but this was like no chair I had ever seen before, made of laminated plywood, curvaceous, fluid and poetic. The original advertising leaflet, designed by another Bauhaus Master, Lszl Moholy-Nagy, suggested that anyone reclining on the Long Chair would imagine they were airborne. I tried out the chair and decided he was right.

This was where the chain of coincidence that led me to Walter Gropius began. The occasion at Dunns was the relaunch of the Long Chair, production of which had been suspended in the war, when plywood parts made in Estonia could no longer be obtained. Among those present was Jack Pritchard, the modernist entrepreneur who had founded Isokon, commissioned Lawn Road Flats in Hampstead and supported Gropius and Breuer while they were in England. He came darting over and I was enchanted by his somewhat risky spontaneity of manner. Within the first two minutes he had invited me to come and spend a weekend at his house in Blythburgh in Suffolk. Over the next twenty years I went there often with my designer husband David Mellor and later with our children. It became a place we could escape to, almost a second home.

That house was like nothing I had ever known before. Jack and his psychotherapist wife Molly presided over a regime of the ever-open door, through which a wonderfully random mix of people architects and scientists, artists and musicians, academics, surgeons, psychoanalysts, inventors endlessly thronged. Conversations on art, science and politics raged non-stop. Children were treated as if they were grown up.

The mood, as I came to realise, was a throwback to progressive Hampstead of the 1930s. Jack never failed to emphasise that the house itself had been designed by his architect daughter Jennifer, the proud result of his liaison with the Hampstead nursery school teacher Beatrix Tudor-Hart. The layout of the building had a lovely flexibility which was later to remind me of Gropiuss own house in Lincoln, Massachusetts. The routine was self-consciously uninhibited. The early-evening sauna with a little birch-twig beating was followed by the obligatory naked plunge into a fairly freezing Suffolk swimming pool. Supper often consisted of Jacks Ultimatum Salad, an amalgam of any food he could lay his hands on in order to feed the often unexpected multitudes. Conversation, which continued way into the night, included many references back to Gropius and Breuer and that whole lost world of pre-war European modernism. There was much detailed talk about the Bauhaus, its personalities, its ethos. This became familiar territory to me too.

Most memorably at Blythburgh art was all around us. The little Henry Moore on the side table in the dining room; the Calder mobiles in the childrens bunkhouse, almost asking to be kicked around. The curtains were designed by the Pritchards friend Ben Nicholson. Art was not treated as sacrosanct, not given ostentatious attention or respect, certainly not regarded as a commercial commodity. It was there to be enjoyed just as part of normal life. This was the driving force behind the original concept of the Bauhaus as envisioned by Gropius. Responding to the horrifying carnage of the First World War, in which technological advances had been harnessed to the weaponry of destruction, the Bauhaus literally the House of Building, with its underlying sense of spiritual reconstruction was Gropiuss attempt at a reversal of this process. Biography as Ive come to see it is a slow-burning process of the making of connections. My original friendship with Jack and Molly Pritchard brought me in the end to Walter Gropius himself.

In autumn 1968 the Bauhaus exhibition arrived at the Royal Academy in London. It had opened originally in Stuttgart, sponsored by the German government at a time when the achievements of Gropius and the Bauhaus were being celebrated in a somewhat desperate attempt to obliterate the memory of their persecution by the Nazis, who had forced the closure of the school in 1933. The exhibition stressed the concept of democratic art as part of the German tradition of the past. For Gropius himself and for the remaining Bauhaus students and teachers, many of whom came to London for the opening, this was a highly emotional time. The exhibition and the catalogue had been designed by the former Bauhaus Master Herbert Bayer. Jack Pritchard took on a delightedly proprietorial role.

He invited me to come to dinner at the Isobar, the Lawn Road Flats restaurant designed by Marcel Breuer, to meet Bayer. In the 1960s, thirty years after it was first designed, the Isobar still kept its authentic period quality. We sat at Breuers plywood table, Jack and Herbert Bayer facing me as I perched on an Isokon plywood stool. Bayer was still handsome, debonair and charming. We talked about the past, about the Bauhaus and Berlin in the 1930s, about Bayers later years of working in New York. What I was only much later to discover was that Herbert Bayers passionate affair with Gropiuss wife Ise had been the one serious threat to their long marriage. One of the fascinations of working on biography is the way in which such submerged histories emerge.

The next day, at a special private viewing of the Bauhaus exhibition, Jack Pritchard introduced me to Gropius himself. He was then eighty-five, small, upright, very courteous, retaining a Germanic formality of bearing, a reminder of how Gropius had once been the glamorous moustachioed officer in the gold-frogged dress uniform of the Hussars.

As he told me, by 1968 he had experienced three disparate lives: first in Germany as a radical young architect and then as the founder and director of the Bauhaus, the flight to England via Rome in 1934, followed by yet another emigration. He had now lived in America for more than thirty years. Gropius had experienced the long life of a wanderer, albeit an especially distinguished one. Though his English had obviously improved greatly since his nervously tongue-tied arrival at Victoria Station, he had never entirely lost his German accent. His face was deeply lined. He was by this time evidently ageing and he died a year later, in July 1969. But Gropius at this point was still valiant and impressive, with a flickering of arrogance. I could see why Paul Klee, one of the first Masters he appointed to the Bauhaus, referred to Gropius in his early Weimar days of authority and glamour as the Silver Prince.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Gropius»

Look at similar books to Gropius. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Gropius and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.