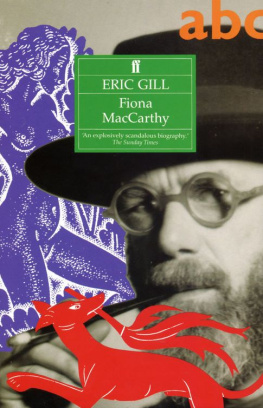

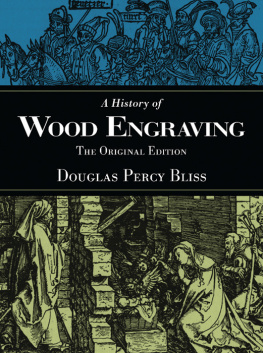

Eric Gill was a great artist-craftsman. Others (though not many) matched him as a sculptor, wood engraver, letter cutter or typographer. But no one has approached his mastery over such a range of activity. In 1913 he was converted to Roman catholicism and became a focal figure in a succession of Catholic art-and-craft communities: at Ditchling in Sussex, at Capel-y-ffin in the Welsh mountains and finally at Pigotts near High Wycombe. In all these places Gill himself, in the familiar stonemasons smock (belted, worn with woollen stockings, never trousers), presided genially over a large household wife, daughters and a whole extended family of craftsmen, priests and passers-through. His aura of holy domesticity invited comparisons with the household of St Thomas More in Chelsea. One susceptible visitor, sitting down to eat with the family at Ditchling after listening to the daily reading of the Martyrology, reported seeing the actual nimbus round Gills head.

Gills chief battle cry was integration. He objected fervently to what he saw as the damaging divisions in society, the rupture between work and leisure, craftsmanship and industry, art and religion, flesh and spirit. He believed that integration must begin with domesticity: the cell of good living in the chaos of our world which he so obsessively set about creating. Gill wrote just before he died:

what I hope above all things is that I have done something towards reintegrating bed and board, the small farm and the workshop, the home and the school, earth and heaven.

Although he stood so ostentatiously apart, stranger in the strange land prophesying devastation, Eric Gill was in spite of himself a well-known public person. He was taken very seriously in his day. At his death, the obituaries suggested he was one of the most important figures of his period, not just as an artist and craftsman but as a social reformer, a man who had pushed out the boundaries of possibility of how we live and work; a man who set examples. But how convincing was he? One of his great slogans (for Gill was a prize sloganist) was It All Goes Together. As I traced his long and extraordinary journeys around Britain in search of integration, the twentieth-century artistic pilgrims progress, I started to discover aspects of Gills life which do not go together in the least, a number of very basic contradictions between precept and practice, ambition and reality, which few people have questioned. There is an official and an unofficial Gill and the official, although much the least interesting, has been the version most generally accepted. The anomalies have, for one reason or another, been ignored or glossed over by his past biographers with a protectiveness we would now consider as superfluous, if not verging on insulting. Gill is too original and too self-reliant as a human being, as well as too important as an artist, to deserve the kind of half-truth treatment to which he has been subjected through the years. The urge to conserve the conventional viewpoint reveals more, I believe, about the commentators than the subject. Most of these commentators have been Catholics. They have chosen to present Gill as a Catholic artist and Catholic thinker whose way of work and worship held together with a kind of sweet reasonableness, ignoring and evading the cumulative evidence suggesting great complexities beneath the surface.

Gills appetite for sex was unusually avid. The diaries he kept with immense care and regularity from his late teens onwards, typically workmanlike records of events, reveal his sexual behaviour was startlingly at variance with his image as father of the devout Catholic family or, at any rate (since Catholic fathers are allowed a little rope), puzzlingly at odds with his public role as sage, pronouncer on morality, upholder of decorum. There is nothing so very unusual in Gills succession of adulteries, some casual, some long-lasting, several pursued within the protective walls of his own household. Nor is there anything so absolutely shocking about his long record of incestuous relationships with sisters and with daughters: we are becoming conscious that incest was (and is) a great deal more common than was generally imagined. Even his preoccupations and his practical experiments with bestiality, though they may strike one as bizarre, are not in themselves especially horrifying or amazing. Stranger things have been recorded. It is the context which makes them so alarming, which gives one such a frisson. This degree of sexual anarchy within the ostentatiously well-regulated household astonishes.

This is the crux of the question as I see it: Gill took the rules on board, even to some extent invented them, and then allowed himself to break them without very much apparent compunction or self-questioning. Yet he was not, I think, a humbug. So there remains the mystery of how the avowed man of religion, Tertiary of the Third Order of St Dominic, habitual wearer of the girdle of chastity, could be by conventional standards so unchaste. It is not a question Gills adherents liked to ask. The material in the diaries would have been available to Gills earlier biographer Robert Speaight, a Catholic and family acquaintance, whose LifeofEricGill came out in 1966, and Donald Attwater, Gills close friend and disciple, whose memoir ACellofGoodLiving was published three years later. Neither of them chose to make much use of it, or of the mutual sex confessions HeandShe which Gill and his wife, in the wake of Havelock Ellis, exchanged in 1913, the year of their conversion. Both Speaight and Attwater prefer what one might call the wild oats view of Gill, referring briefly to his youthful fling in his socialist period with Lillian Meacham, the Fabian New Woman. This affair, culminating in reckless flight to Chartres, is described by Gill himself, rather vaguely, in his memoirs. The episode is used by his biographers as Gills one licensed aberration, with the implication that it had taught him the error of his ways.

But Lillian did not fade out of the picture, as Speaight so complacently assured his readers: it would not have been beyond the competence of a professional biographer of Robert Speaights experience to establish the fact that Lillian, who eventually married George Gunn, Professor of Egyptology at Oxford, and whose son Spike Hughes delineated her fondly in his own autobiography, remained a family friend until Gills death. Nor is it quite accurate to claim, as Donald Attwater does blithely, that after the Chartres escapade Mary and Eric had lived happily ever after. That they were happy in a sense is beyond doubt. But their marriage had its storms and complications, and to suggest otherwise is surely to belittle the nature of a man fearfully and wonderfully made the adventurer in life as Roger Fry described him and an artist whose work is on the edge of a new phase of popularity. Gill speaks in our own language, with vigour and directness. In few other artists of this century are images of the erotic and domestic, the sexual and devotional, so closely and so disconcertingly related.

My own interest in Gill began in 1966, the year Speaights book was published. I was then design correspondent on the Guardian. Father Brocard Sewell, who knew Ditchling well from the days when he had worked at St Dominics Press, suggested the Guild workshops still existing on the common might be worth investigating. On that visit I met several of the craftsmen who had known Gill well, including Joseph Cribb, his original apprentice. It struck me how vividly the place still bore the imprint of Gills own personality It was, after all, forty years since he left Ditchling and well over twenty years since he had died. But he was still a central, and indeed a controversial topic of conversation, bearing out the comment of Gills friend, Beatrice Warde, most articulate and sophisticated of his mistresses, who maintained that those who had known Eric Gill went on talking about him ever afterwards.