EPILOGUE

SICK AT HEART, AND PHYSICALLY ILL, I started my long voyage homeward. The trip was not a pleasant one: everywhere I looked I saw, where flourishing cities and towns had once stood, nothing but gutted ruins and the collective, white-crossed graves of the dead.

I dreaded the truth, fearing to return to an empty, plundered home, a home where neither parents nor wife, daughter nor sister, would be waiting to greet me with warmth and affection. Persecution and sorrow, the horrors of the crematorium and funeral pyres, my eight months in the kommando of the living dead, had dulled my sense of good and evil.

I felt that I should rest, try to regain my strength. But, I kept asking myself, for what? On the one hand, illness racked my body; on the other, the bloody past froze my heart. My eyes had followed countless innocent souls to the gas chambers, witnessed the unbelievable spectacle of the funeral pyres. And I myself, carrying out the orders of a demented doctor, had dissected hundreds of bodies, so that a science based on false theories might benefit from the deaths of those millions of victims. I had cut the flesh of healthy young girls and prepared nourishment for the mad doctors bacteriological cultures. I had immersed the bodies of dwarfs and cripples in calcium chloride, or had them boiled so that the carefully prepared skeletons might safely reach the Third Reichs museums to justify, for future generations, the destruction of an entire race. And even though all this was now past, I would still have to cope with it in my thoughts and dreams. I could never erase these memories from my mind.

At least twice I had felt the wings of death brush by me: once, prostrate on the ground, with a company of SS trained in the art of summary execution poised above me, I had escaped unharmed. But three thousand of my friends, who had also known the terrible secrets of the crematoriums, had not been so lucky. I had marched for hundreds of kilometers through fields of snow, fighting the cold, hunger, and my own exhaustion, merely to reach another concentration camp. The road I had traveled had indeed been long.

Now, home again, nothing. I wandered aimlessly through silent rooms. Free, but not from my bloody past, nor from the deep-rooted grief that filled my mind and gnawed at my sanity. And the future seemed just as dark. I walked like my own ghost, a restless figure in the once familiar streets. The only times I managed to shake off my state of depression and lethargy was when, mistakenly, I thought for a fleeting second that someone I saw or briefly encountered on the street was a member of my family.

One afternoon, several weeks after my return, I felt chilly and sat down near the fireplace, hoping to derive a little comfort from the cheerful glow that filled the room. It grew late; dusk was falling. The doorbell roused me from my daydreams. Before I could get up to answer it my wife and daughter burst into the room!

They were in good health and had just been freed from Bergen-Belsen, one of the most notorious of the extermination camps. But that was as much as they were able to tell me before breaking down. For hours they sobbed uncontrollably. I was content just to hold them in my arms, while the flood of their grief flowed from their tortured minds and hearts. Their sobs, a language I was well familiar with, slowly subsided.

We had much to do, much to relate, much to rebuild. I knew it would take much time and infinite patience before we could resume any sort of really normal life. But all that mattered was that we were alive... and together again. Life suddenly became meaningful again. I would begin practicing, yes... But I swore that as long as I lived I would never lift a scalpel again....

I

MAY, 1944. INSIDE EACH OF THE locked cattle cars ninety people were jammed. The stench of the urinal buckets, which were so full they overflowed, made the air unbreathable.

The train of the deportees. For four days, forty identical cars had been rolling endlessly on, first across Slovakia, then across the territory of the Central Government, bearing us towards an unknown destination. We were part of the first group of over a million Hungarian Jews condemned to death.

Leaving Tatra behind us, we passed the stations of Lublin and Krakau. During the war these two cities were used as regroupment campsor, more exactly, as extermination campsfor here all the anti-Nazis of Europe were herded and sorted out for extermination.

Scarcely an hour out of Krakau the train ground to a halt before a station of some importance. Signs in Gothic letters announced it as Auschwitz, a place which meant nothing to us, for we had never heard of it.

Peering through a crack in the side of the car, I noticed an unusual bustle taking place about the train. The SS troops who had accompanied us till now were replaced by others. The trainmen left the train. From chance snatches of conversation overheard I gathered we were nearing the end of our journey.

The line of cars began to move again, and some twenty minutes later stopped with a prolonged, strident whistle of the locomotive.

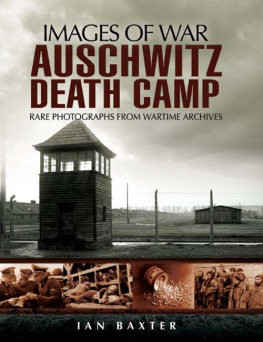

Through the crack I saw a desert-like terrain: the earth was a yellowish clay, similar to that of Eastern Silesia, broken here and there by a green thicket of trees. Concrete pylons stretched in even rows to the horizon, with barbed wire strung between them from top to bottom. Signs warned us that the wires were electrically charged with high tension current. Inside the enormous squares bounded by the pylons stood hundreds of barracks, covered with green tar-paper and arranged to form a long, rectangular network of streets as far as the eye could see.

Tattered figures, dressed in the striped burlap of prisoners, moved about inside the camp. Some were carrying planks, others were wielding picks and shovels, and, farther on, still others were hoisting fat trunks onto the backs of waiting trucks.

The barbed wire enclosure was interrupted every thirty or forty yards by elevated watch towers, in each of which an SS guard stood leaning against a machine gun mounted on a tripod. This then was the Auschwitz concentration camp, or, according to the Germans, who delight in abbreviating everything, the KZ, pronounced Katzet. Not a very encouraging sight to say the least, but for the moment our awakened curiosity got the better of our fear.

I glanced around the car at my companions. Our group consisted of some twenty-six doctors, six pharmacists, six women, our children, and some elderly people, both men and women, our parents and relatives. Seated on their baggage or on the floor of the car, they looked both tired and apathetic, their faces betraying a sort of foreboding that even the excitement of our arrival was unable to dispel. Several of the children were asleep. Others sat munching the few scraps of food we had left. And the rest, finding nothing to eat, were vainly trying to wet their desiccated lips with dry tongues.

Heavy footsteps crunched on the sand. The shout of orders broke the monotony of the wait. The seals on the cars were broken. The door slid slowly open and we could already hear them giving us orders.

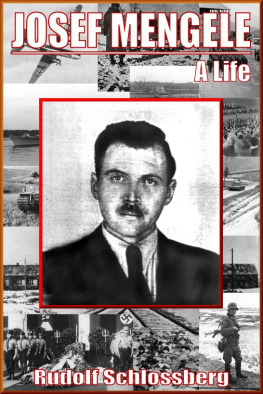

Everyone get out and bring his hand baggage with him. Leave all heavy baggage in the cars.

We jumped to the ground, then turned to take our wives and children in our arms and help them down, for the level of the cars was over four and a half feet from the ground. The guards had us line up along the tracks. Before us stood a young SS officer, impeccable in his uniform, a gold rosette gracing his lapel, his boots smartly polished. Though unfamiliar with the various SS ranks, I surmised from his arm band that he was a doctor. Later I learned that he was the head of the SS group, that his name was Dr. Mengele, and that he was chief physician of the Auschwitz concentration camp. As the medical selector for the camp, he was present at the arrival of every train.