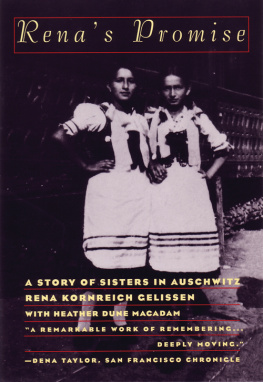

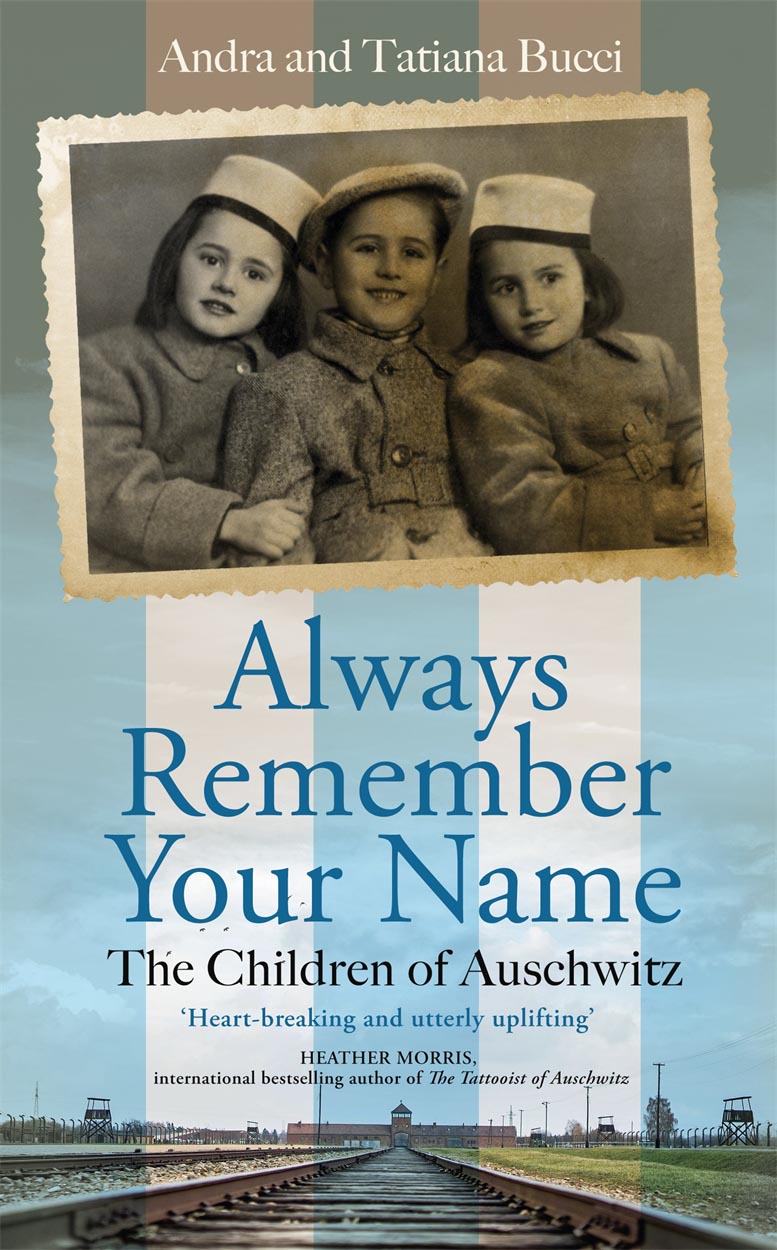

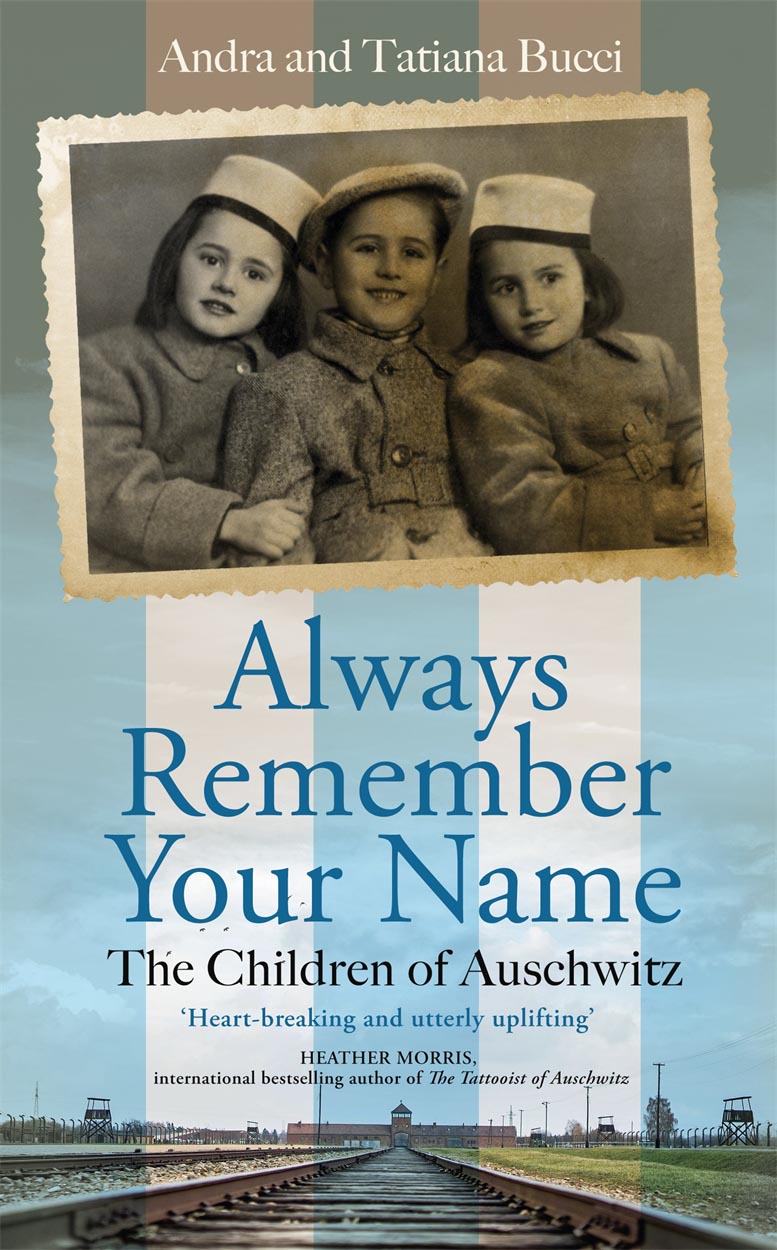

We dedicate this book to all the children of Auschwitz: to the few who, like us, survived and to the many who did not

My name is Liliana Bucci, but Im called Tatiana. I was born in Fiume on September 19, 1937, and Im one of the very few children who survived the Auschwitz extermination camp.

I am Alessandra Bucci, but Ive always been called Andra. I was born in Fiume on July 1, 1939, and like my sister, Tati, Im one of the very few children who survived the Auschwitz extermination camp.

Contents

IN JANUARY 2020, I received an email from Barbara Pierce, whom I didnt know, but who wanted to enlist my help in getting translated into English, and published, a book she had just read in Italian, Noi, Bambine ad Auschwitz, the story of two Italian sisters deported to Auschwitz at the ages of four and six. She had found the book deeply moving, and was passionate about getting it to a broader, English-speaking audience. She sent me the book, which I, too, found compelling and certainly deserving of a larger audience, and I agreed to start by translating a sample chapter. After trying various editors, publishers, and other avenues, we came to Alessandra Bastagli, the editorial director of Astra House, who is a translator of the survivors Primo Levi and Jurek Becker and publisher of other books about the Holocaust (including a book about Levi and a memoir by another Italian survivor, Piera Sonnino), and who was as enthusiastic as we were about publishing the book.

Three things struck me about Noi, Bambine ad Ausch witz: The first was that the sisters were so young when they were arrested and deported. The second was that the storys narrative voice is the first-person plural, the we, and yet the authors beautifully sustain the sound of two voices, sometimes in unison and sometimes in dialogue; the insertions of one sister or the other into the we happen naturally and smoothly. Third, I was fascinated by the account of the sisters lives after Auschwitz and of how they were able to return to the camp, both physically and emotionally, in order to tell their story to others, to bear witness. Not only that: I was also fascinated by how they came to the conviction that it was extremely importantcrucialfor them to do this.

TATIANA AND ANDRA Bucci were born and spent their early lives in Fiume, on the Adriatic coast in what is now Croatia; today it is the Croatian city of Rijeka. The family of their mother, Mira Perlow, were Russian Jews who, probably fleeing a pogrom, arrived in the port city, which was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in 1910. The family included Miras parents, Rosa and Moise Perlow, and five of their six children (the sixth was born in Fiume), and Rosas parents, Lazzaro and Lea Farberow, along with their six children and their children. From Fiume, many in this large family group continued on to America, but the Perlows remained (for one thing, apparently, they liked the fact that it was on the sea, so that it would be easier if they were forced to flee again). At the time of their arrival, nearly half the population of around fifty thousand was Italian, while the rest were mainly Croatian and Hungarian. There was a solid Jewish community, with many Jews having arrived in the 1870s and 80s, and a new synagogue had been built around the turn of the century. After the First World War, Italy and Yugoslavia both claimed Fiume, and it was briefly divided between them; in 1924 it was annexed to Fascist Italy and remained Italian until 1945. Moise Perlow seems to have gone off to fight in the First World War, from which he did not return. Tatiana and Andras father, Giovanni Bucci, was an Italian Catholic, born in Fiume, who worked as a ships cook and was rarely home. The sisters grew up with their mothers family.

In the fall of 1938 Mussolini announced the racial laws, which restricted the civil rights of Jews, excluding them from public schools, universities, politics, finance, the professions, and all sectors of public and private life. Thus, the children couldnt go to school and the adults lost their jobs; as the sisters write, We spent some difficult months. Neither parent was religious, but with the promulgation of the racial laws Mira Perlow tried to catholicize her daughters by having themand herselfbaptized. In June 1940, Italy entered the war on Germanys side, which caused further hardships in daily life. Giovanni Bucci was on a ship off South Africa and was arrested and sent to a prison camp near Johannesburg, where he spent the entire war.

Although the racial laws were restrictive, people were able to live, as the sisters recall in an interview. Then, in July of 1943, Mussolinis government fell, and on September 8, Italy surrendered to the Allied forces. The Germans took over the country from Rome north. Fiume immediately became part of the Adriatic Littoral Zone under control of the Nazi-Fascists, and the deportation of its Jews began. A poignant moment of the Buccis story is the failure of their mother to find anyone who would be willing to hide them. Some members of the Perlow family fled, ending up in a small town near Vicenza, but they were eventually captured. In March of 1944 the Perlows remaining in Fiume were arrested; they had been informed on, they believe, by someonean Italianwho worked in the synagogue (and who presumably received money for his information). Of the thirteen family members ultimately arrested and imprisoned, four returned.

TATIANA AND ANDRA arrived in Birkenau on April 4, 1944, and spent ten months there. For much of that time their mother was also there, and although her barrack was on the other side of the camp, she managed to visit them several times. In November she was transferred to another camp; she was then transferred to Buchenwald and eventually returned home after the war. The girls, however, remained in Birkenau, and were liberated on January 27, 1945, by the Russian Army.

We might expect that the sisters story after the liberation would be a less absorbing one. But their path from the Polish city of Katowice to Prague, then to Lingfield, in England, and finally to Rome and then Trieste, where the family moved because Fiume had become part of Yugoslavia, is both dramatic and affecting. We should not forget that when they returned to their parentsan unusual and incredibly fortunate outcomethey were only nine and seven, and for almost two years had assumed their mother was dead.

When their family was reconstituted, there seems to have been a kind of unspoken agreement that no one would discuss the concentration camp experiences: the mother and daughters didnt talk, even to one another, about Auschwitz and its aftermath (Between us, the sisters say of their mother, was an impenetrable, total silence), although the father spoke of his own five-year imprisonment in South Africa. The sisters talked about Lingfield House, a center outside London for children displaced or orphaned by the war, where they had a happy interlude and were able to regain something of their lost childhood. Their mother and auntthe only other survivors in their familytold them how they had returned from the camps, but they didnt discuss it or ask the sisters questions. Their mother, as they say, seems to have made a determined effort to turn them toward the future, rather than the past, and enable them to construct normal lives for themselves.

In part, too, the atmosphere of the immediate postwar period was not conducive to the news from the camps: people did not believe what the survivors had to tell. Priorities were different: Italians were involved in rebuildingthemselves, their lives, their countryand wanted to cancel out the past. In an interview the sisters point out that when their mother returned, her friends asked where she had been, what had happened to her, but wouldnt believe what she told them: What are you talking about, Miretta? theyd say. Primo Levi, in

Next page