Dear Mama and Papa:

This book is for you. For fifty years Ive been telling you this story in my mind.

Now its finally written down and I wont have to tell it anymore.

Love, Rena

And for Danka: Without you there would be no story.

The Story (for Rena)

It goes on burning in the bones,

in the brain, years after, smoke

still rising behind the walls, even on

May second, a birthday to liberate

all others. In Poland, though the stone

well-water near Tylicz never ceases,

it never soothes the smoldering,

nor the fearful dreams fueling sleep.

For months a redwood tree can flame

the fire that consumes it, burning

a black scar to its core. Within the

burnt sepulchre, as if a miracle, seeds

bearing a young tree begin to green. Let

us sift the ashes for new life, for the story

forged in suffering; where the birth into

language is as terrifying as fire or love.

by Annette Allen

Note to reader: Maps may also be found online at www.renaspromise.com .

PROLOGUE

I touch the scar on my left forearm, just below the elbow. I had the tattoo surgically removed. There were so many people who didnt know and so many questions: What do those numbers mean?

Is that your address? Is that your phone number?

What was I supposed to say That was my name for three years and forty-one days?

One day a kind doctor offered to remove it for me. This is not charity, he assured me. It is the least I can do as an American Jew. You were there, I was not.

So I chose to have the questions excised from my arm, but not my mindthat can never be erased. The piece of skin the doctor surgically removed rests in a jar of formaldehyde which has turned the flesh to an eerie green. The tattoo has probably faded by now, I havent checked. I need no reminders. I know who I am.

I know what I was.

I was on the first transport to Auschwitz. I was number 1716.

Rena Kornreich Gelissen, January 1994

RENA

It is a crisp Saturday morning in January and my car wends its way from the foothills of North Carolina toward where the Blue Ridge Mountains crest a blue grey horizon, like waves caught in time. As I come around the last of the hairpin curves and pass the eastern divide, my breath catches. Sunlight shatters a cloud bank above the valley of Asheville, like a good omen.

I love this drive. Without fail it always rejuvenates my spirit and my heart. That is a good thing because I am about to make this journey every weekend for the next four months, and the place I am heading will be anything but light. I am going to meet one of the few survivors from the first transport of women to Auschwitz, a woman who after almost 50 years of silence has finally decided to tell her story.

I have only spoken to Rena twice, and it seems we have been putting off this meeting for months now, but with the holidays finally over and the snow storms finally passed, we have no more excuses. My thoughts tumble across one another; I am uneasy about the task Im about to undertake. Helping Rena tell her story without either of us drowning in the undertow of painful memories would be a tall task for a psychologistI am merely a writer.

However, I have my reasons for wanting to work with Rena. My family was Quaker and hid slaves just north of the Mason Dixon line, before and during the Civil War; my grandmother was the first restaurant owner to openly welcome members of the NAACP, when they came to town to promote Civil Rights. I grew up knowing that if my family had been in Europe during World War II, we would have risked our lives to save the Jews. We would have risked our lives to save Gypsies too.

Over the past year, I have volunteered at a hospice grief counseling center, where I helped children who had lost parents or significant caregivers write a book about grief. Now I am about to attempt a similar story on a much larger scale. That is, if Rena likes me. I am secretly afraid that I will come up wanting in her eyes because I am not Jewish, because I am not Polish, because I am American, because I am young. Maybe Im not the best person for this job.

The first time we spoke on the phone I was cooking pierogies and kielbasa for dinner.

Are you Polish? she asked excitedly.

No, I told her. I just love pierogi. We used to eat them at an all night diner called The Kiev, on the Lower East Side in New York.

I think Id like that place. We bonded over pierogi.

Renas house lies in a small valley, with a pasture full of grazing cows behind it. Trussed across the horizon, hemming us in on all sides, are the voluptuous curves of the southern mountains. In the driveway, I organize my thoughts and my book bag before stepping out of the carit has taken me just under two hours to get here from where I live in North Carolinas piedmont. The air is cooler up here, but the sun is strong and the wind, though it has a nip of winter, has none of its cruelty.

Inside, I am greeted warmly by Renas husband, John. We shake hands and he calls out, Mama! A beautiful lady is here to see you!

Rena bustles down the hall toward the kitchen, a tiny dynamo of energy. She is not at all what I expect. She is lively, cheerful, chatty. Papa, invite her to sit down. Oh, youre so tall! She smiles up at me.

I am? Im the short one in my family.

Im the tall one in mine. Her eyes twinkle.

Heather, come see Renas linen closets! John waves to me to follow him down the hallway.

Jan, no! She starts to reprimand him in Dutch, then, for my benefit, adds in English, Youre embarrassing me.

Mama, you spent all day yesterday straightening them, at least let Heather see your hard work. How else will she know?

Thats not true. Theyre always this neat, she says with pride.

Showing me the beautiful linens she has collected over the years, she says quietly, I didnt have any linens or heirlooms from my family. So I collected my own at yard sales. I have stayed up til three in the morning scrubbing stains out that somebody else thought were impossible to remove.

There. Now Heather knows how neat and clean you are. Heather, are you going to clean out your linen closets when we come to visit? John teases.

I dont have linen closets, I tell them and joke, Youll be lucky if I dust.

Rena takes my arm. Dont you dare clean for me! I clean too much. When I get nervous I cant stop.

Our banter is light hearted and friendly. There is no ice to break. It is like we have known each other forever. And this meeting, which was supposed to be probationary, quickly turns into acceptance. Within thirty minutes of meeting Rena I know I will do whatever I can to help her, and within the same amount of time, she has accepted me into her heart, for the rest of her life.

I just want my children to read my story someday. I cant tell it to them. I tried but its too hard. And that first day I know that if nothing else I will do that for hershe deserves that much.

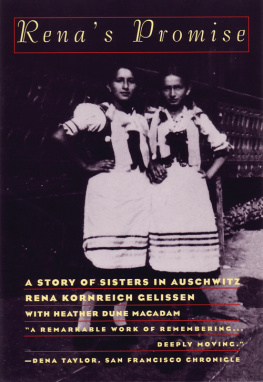

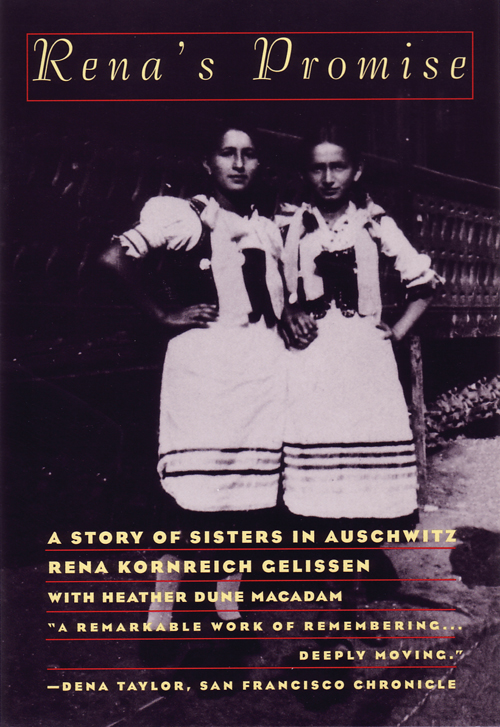

In the basement, where we will spend many hours over the next year exhuming the past and embracing ghosts, there is a gas fire flickering. The room has a rosy glow from the pink sheers she has hung over the windows. From the pink room with its fire, she leads me into an adjoining room where the family photos are on display. The wall is divided into two sections: the Gelissen family, from Holland, on the left and the Kornreich family, from Poland, on the right. In the middle are Rena and Johns wedding photo and pictures of their children. Rena tells me that she wouldnt have any prewar photos if her eldest sister, Gertrude, hadnt immigrated to America before the war.