IT WAS BITTER COLD the night German police forced me and my mother into a cattle car and sent us from Plaszow, Poland, to Auschwitz, the largest of all Nazi killing centers. The train was made up of two cattle cars. There were 150 women prisoners crammed into each of the two cars. I was fourteen years old, one of the youngest. We arrived at Auschwitz late at night. Guards slammed open the doors of the cattle car and yelled at us to jump out. Then they marched us into a long wooden barrack with rows of benches along the walls.

Take off all your clothes! the guards shouted. You will be brought back here to collect your things laterafter your shower.

The guards shoved us into a room maybe twenty feet by twenty feet. It was dark, but we could see pipes running the length of the ceiling. Back home in Krakow, we had heard scary rumors about what happened to Jews in concentration camps. What kind of shower was this? Were we going to die?

If you were not there in the death camp at Auschwitz, you cannot imagine it, and I cannot truly describe it. Still, for most of my adult life, I have been trying as best I can to teach about the Holocaust in middle-grade schools and colleges, in church groups and synagogues. Like many other survivors, I feel an obligation to tell my story again and again. The Holocaust was the scientifically designed, state-sponsored murder of the Jewish people by Nazi Germany and its allies. The Holocaust should never be forgotten and should never happen againbut how can we protect against that? You, dear reader, can help. One person with courage to stand up for the innocent can make a big difference.

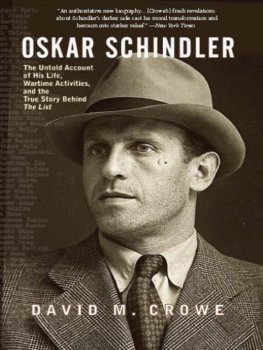

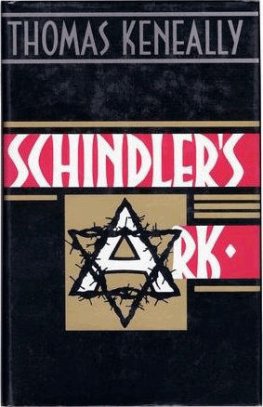

I should know. Im alive thanks to someone who refused to stand by and do nothing. His name was Oskar Schindler.

TO UNDERSTAND THE STORY you are about to read, it will help to know something about my childhood and where I came from. Please keep in mind that today I am ninety years old. These are the memories of a girl in her early teens, and some memories change over time. I cannot promise you that everything happened exactly as I am recalling. After so many years, some details may be less than perfect. What I can promise you is that everything I tell you is truthful and that these things did happen.

I was born in 1929 in Krakow, Polands historic capital city. Krakow was a center of the nations artistic and cultural life. It had a famous university attended by students from around the world. Electric streetcars crisscrossed the city, bringing people to offices, museums, and libraries.

I lived with my mother, Rosa, and my father, Moses, in one of Krakows many apartment buildings. Our building was a few blocks from the center of the city and next door to a Franciscan monastery. There was a balcony off the stairway landing below our fourth-floor apartment. From the balcony, I could look into the monasterys backyard, where there were fruit trees and flowering bushes. In the early morning hours, monks walked slowly around the backyard in their long brown robes, praying on strands of wooden beads. My memories of early childhood are, for the most part, like that orchard: calm and pleasant.

My parents bedroom had a large wooden clothes closet. In the kitchen was an iron cookstove that burned coal. A Polish woman came once a week to clean, and on cold days she took a metal bucket, walked down four flights of marble stairs to the cellar, filled the bucket with coal, and carried it back upstairs. Heat from three coal-burning ovens warmed the whole apartment.

I remember other details from my childhood. Our main language at home was Polish, but my mother hired a tutor who taught me German. Because of all the later horrors that happened to me and my family at the hands of Nazi Germany, once I came to America, I never wanted to hear German spoken ever again.

My father was a good man: loving, attentive to me and my mother, and always looking to do good for others. He earned a living as a salesman for a company that made surgical instruments and hospital supplies. He left Krakow every Monday morning by train to visit out-of-town customers and returned on Friday in time for the start of the Sabbath. The Sabbaththe time between sunset on Friday and sunset on Saturdayhas always been the most sacred part of the week for Jews. During those twenty-four hours, religious Jews dedicate their time to religious study and do no work. Even turning on a light switch is considered work and forbidden on the Sabbath.

I was an only child, but my mother had six siblings and my father had seven. My mothers parents, Hannah and Isaac, had their own apartment around the corner from us. I had cousins who lived on the other side of the Vistula River, which flowed around the city, and my mothers siblings lived in Berlin, Germany, about eight hours away by train. So as a child, I was surrounded by family. In summer, we all came together and rented a cottage in the village called Zawoja, near a famous mountain known as Baba Gura (Baba Mountain), where we hiked, swam in freshwater streams, and picked juicy strawberries and wild mushrooms.

There was an elderly woman who took care of us on summer days while my parents, aunts, and uncles went hiking up Baba Mountain. One time, when the grown-ups were out mountain climbing, the sky grew dark, a heavy rainstorm began, and thunder shook the windows. We kids werent so scared, but the nanny was terrified and insisted we all kneel down and pray. It felt funnywhat did a bunch of Jewish kids know about Christian prayers?but we did it anyway to make her happy.

These days, when Im invited to speak about my childhood, students often ask if I experienced anti-Semitism. Yes, I did. Many of our neighbors didnt bother hiding their hatred of Jews. Of course, each person who endured the Holocaust has particular memories, and conditions were different depending on where people grew up and how they were treated. In my case, growing up in Krakow, the anti-Semitism was obvious. You could see it in peoples faces when they looked at you. Sometimes they did worse than just look, as I found out when I was six years old and starting school.

Krakow had a large Jewish population: about 60,000 of the citys 200,000 residents were Jews. There was a private Jewish girls school, but it was a few miles away from our building, and my parents didnt like the idea of me walking such a long distance alone. Instead, they sent me to a public school around the corner from our house. The school was so close that my mother could stand on the balcony of our apartment and watch me playing in the schoolyard, to be sure I was safe.

My first day in kindergarten, a few of us five- and six-year-olds were playing hopscotch in the schoolyard. Without warning, one of the girls picked up a stone and threw it at me.