Contents

Ebook ISBN9781590519998

The translation of this work was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institute that is funded by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Federal Republic of Germany.

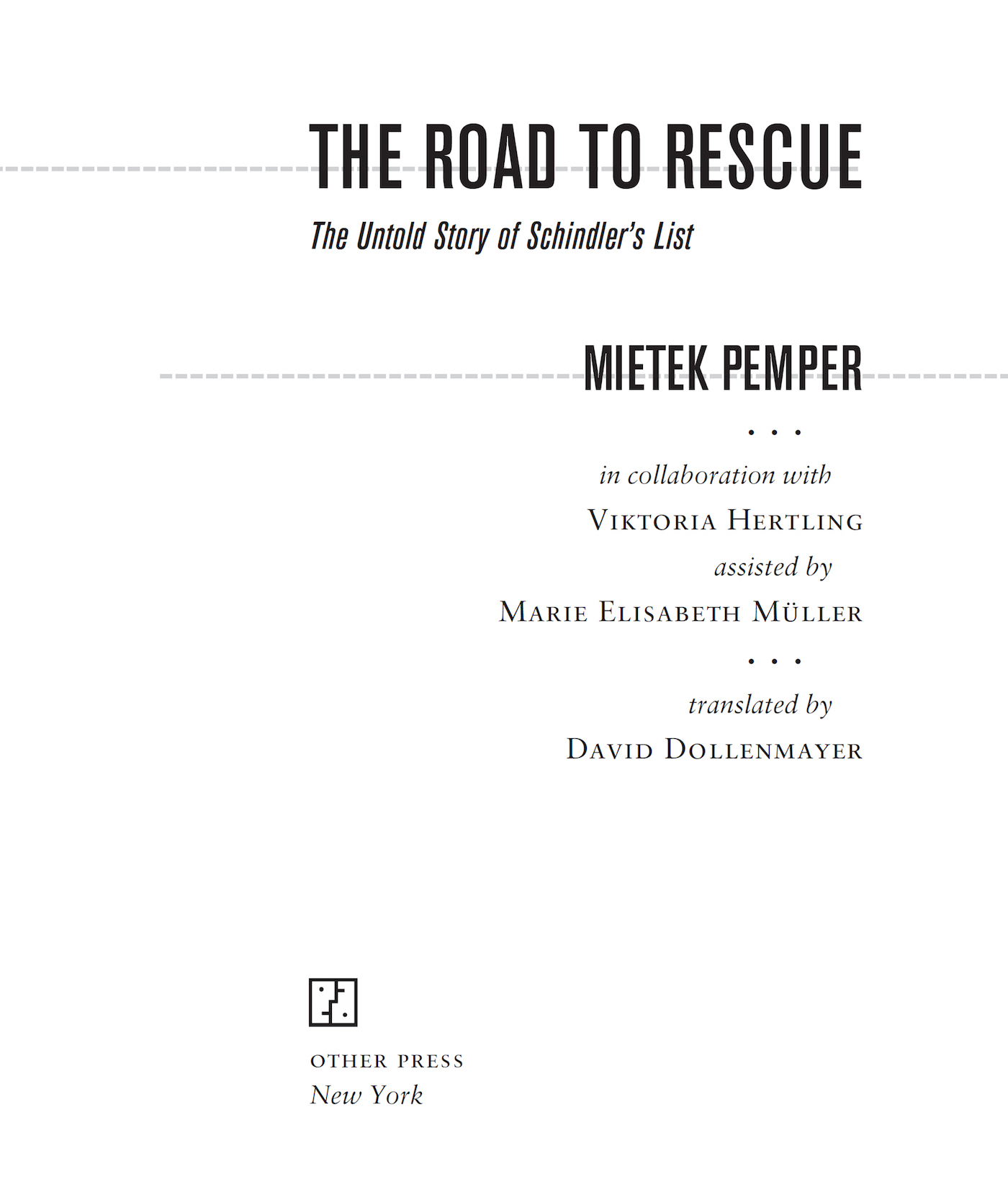

Originally published in German as Der rettende Weg: Schindlers Liste. Die wahre Geschichte by Mietek Pemper.

Copyright 2005 Hoffmann und Campe Verlag, Hamburg

Translation copyright 2008 David Dollenmayer

Production Editor: Yvonne E. Crdenas

Text design: Simon M. Sullivan

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press LLC, 267 Fifth Avenue, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10016.

Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Pemper, Mieczyslaw, 1920

[Rettende Weg. English.]

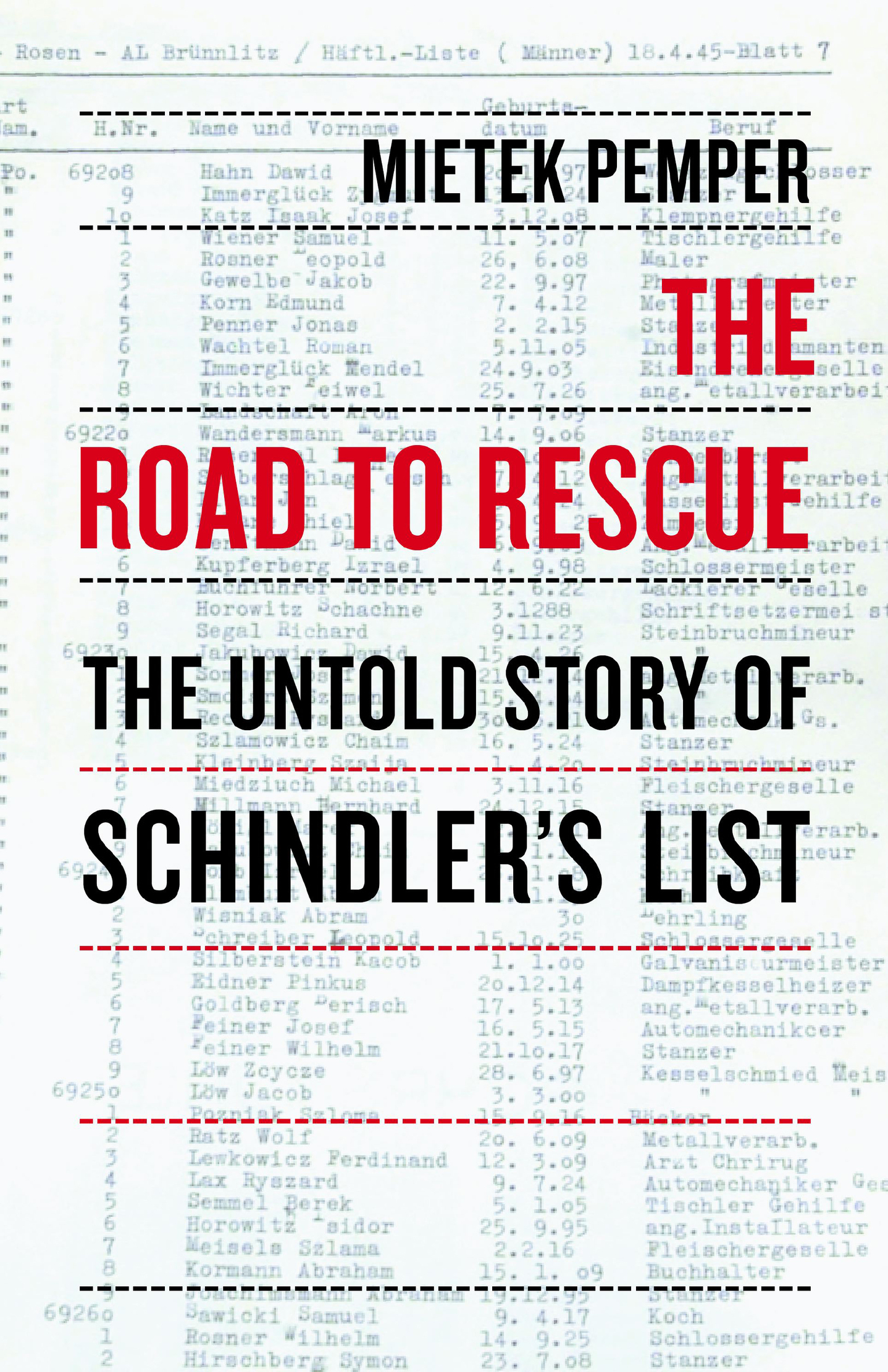

The road to rescue : the untold story of Schindlers list / Mietek Pemper; in collaboration with Viktoria Hertling, assisted by Marie Elisabeth Mller; translated by David Dollenmayer.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-59051-286-9

1. Schindler, Oskar, 19081974. 2. Righteous Gentiles in the HolocaustBiography. 3. World War, 19391945JewsRescue. 4. Pemper, Mieczyslaw, 1920 5. JewsPolandKrakwBiography. 6. Concentration camp inmates PolandPlaszwBiography. 7. Plaszw (Concentration camp) 8. Holocaust, Jewish (19391945)PolandPersonal narratives. I. Hertling, Viktoria. II. Mller, Marie Elisabeth. III. Title.

D 804.66. S 38 P 4613 2008

940.53183dc222008007193

v5.3.1

a

I N MEMORY OF THE MILLIONS OF H OLOCAUST

VICTIMS AND IN HONOR OF O SKAR S CHINDLER ,

WHOSE COURAGE ALLOWED MORE THAN

A THOUSAND J EWS TO SURVIVE .

CONTENTS

PREFACE

The occupation of Poland by Hitlers troops on September 1, 1939, was the beginning of a six-year martyrdom for large sections of the Polish population, especially for the Polish Jews. I feel a special obligation to report on those years of German occupation and the horrors of the camps. Although it seemed almost hopeless, some of us managed to survive. Against the deadly backdrop of war, persecution, and mass murder, I met honorable people on both sides of the conflict.

Jewish victims are often accused of not having engaged in resistance against the Nazis. But what could we have achieved, without weapons, against a brutal power equipped with the latest military technology? To be sure, there were some who attempted armed resistance against the National Socialist occupiers. In Krakw, as in other cities, their fury erupted in a series of assassinations. Unfortunately, with few exceptions, such actions were doomed to failure. These idealistic young people were almost always tracked down and ruthlessly murdered by the Sicherheitspolizei, the German security police. My God, I thought to myself, how can these brave individuals with a couple of homemade bombs expect to compel a powerful country that has conquered almost all of Europe to change its policies? Of course, these were important symbolic acts. They proved that Jews did not simply stand idly by while being systematically stripped of all their rights. However, such acts also provoked horrific reprisals from the Nazi occupiers, to which many Jews fell victim. Was it justified, I asked myself, to take such risks? Or was there perhaps another road, an alternative? At the time, I did not know what this alternate path might look like. But one thing was always certain: I wanted to preserve human life without having to resort to violence.

Krakw-Paszwfirst a forced labor camp and then, from January 1944, a concentration campwas a special case among the approximately twenty concentration camps. It was the only major concentration camp under German control that had begun as a Jewish ghetto. I know this because I spent almost all of my time in Paszw as the involuntarily recruited personal stenographer and secretary of the camp commandant, Amon Gth. Just how unusualand even contrary to the Germans own rulesmy job in the main office of a concentration camp was, I learned only later, when testifying in the 1951 war crimes trial of the SS-Standartenfhrer Gerhard Maurer in Warsaw. Until 1945, Maurer was the supervisor of all camp commandants, in charge of work assignments for all camp inmates. More than a half-million people were under his command. At first, Maurer refused to believe my testimony that I had worked as the personal secretary of a camp commander and, as such, had had access to classified documents. During his trial, Maurer was almost speechless with astonishment that Amon Gth had gotten away with flouting strict regulations to such an extent. By the time Maurers trial took place, I had already testified as the main witness for the prosecution in the 1946 trial of Amon Gth. But in that earlier trial, the extraordinary nature of my job had not even come up. Only Maurers consternation in 1951 made me realize how unique my position in the Paszw camp had been during the Holocaust. This was later confirmed by Holocaust scholars.

As a consequence of more than 540 days spent in the epicenter of evil, my life is inextricably connected to the history of the Krakw-Paszw camp. I worked in the camp headquartersat first as the sole clerical workerfrom March 18, 1943, until September 13, 1944. But it was also there that my life became just as inextricably connected to Oskar Schindler, with whom I worked closely during much of that time and until May 8, 1945. I think it is fair to say that a higher percentage of Jews survived the Paszw camp than other camps. That was the result of Schindlers rescue efforts, for one thousand survivors on Schindlers list were from our camp. My parents, my brother, and I owe our lives to Oskar Schindler.

The history of the Holocaust is closely intertwined with developments on the eastern front. At first, the German Wehrmacht and its allies had a clear advantage. That changed only after the enormous losses they suffered in their invasion of the Soviet Union, especially after the German defeat at Stalingrad. From February 1943, the Nazi wartime economy was in deep crisis. Industrial workers were in short supply and the rate of the mass murder of Jews had slowed down. On the other hand, the productivity of camp inmates increased dramatically. In early 1943, in his infamous speech at the Berlin Sportpalast, Joseph Goebbels had whipped up the German people to the point of accepting total war. From then on, the entire economy was focused on increased weapons production. For us few remaining Jews, this was decisively important. In the fall of 1943, several ghettos and forced labor camps in the Generalgouvernement that produced mainly textiles were disbanded. However our camp, Krakw-Paszw, remained open. In the main office of the camp, I was able to gain access to classified documents and was secretly involved in keeping the camp from being liquidated. Thus, several thousands of my fellow inmates were not deported to Auschwitz. Without this strategy, described in detail in the pages that follow, the rescue by Oskar Schindler one year later during the fall of 1944 would not have been possible.