Dennis Marks - Wandering Jew: The Search for Joseph Roth

Here you can read online Dennis Marks - Wandering Jew: The Search for Joseph Roth full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2016, publisher: New York Review Books, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Wandering Jew: The Search for Joseph Roth

- Author:

- Publisher:New York Review Books

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Wandering Jew: The Search for Joseph Roth: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Wandering Jew: The Search for Joseph Roth" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Wandering Jew: The Search for Joseph Roth — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Wandering Jew: The Search for Joseph Roth" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

During his long and distinguished career in film and broadcasting, Dennis Marks made documentaries on cultural subjects ranging from Janek to Russian history. During the 1990s, he was General Director of English National Opera. His search for Joseph Roth grew out of his acclaimed BBC Radio 3 series on the Habsburg Empire, Faultline. He died in April, 2015

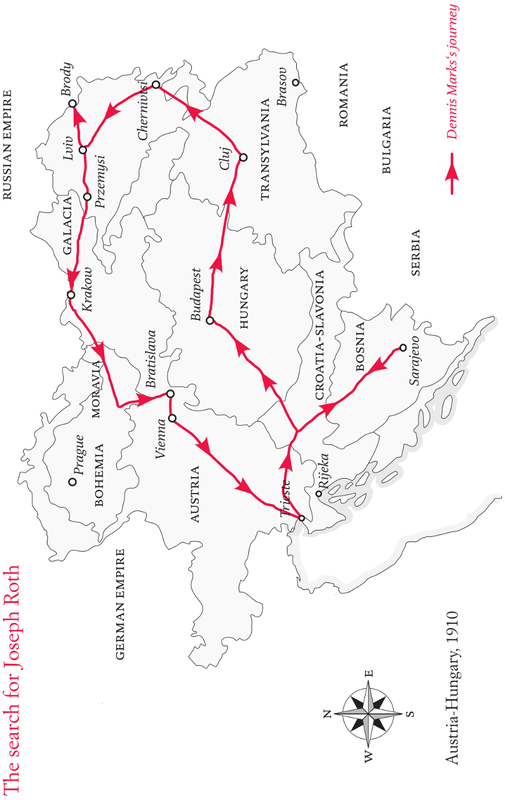

This is history at its most vivid. The Times

H e keeps disappearing. Ten years ago I thought that I had found him, on the wrong side of the tracks in the little town of Brody, on the dusty eastern edge of Europe, where the Empire of the Habsburgs once dissolved into the Empire of the Romanovs. I had come to Brody at the end of a fitful eight-week journey along the boundaries of that Empire, across Austria to the fringes of Italy, down into former Yugoslavia and through Hungary and Romania to the muddy marches of Western Ukraine. I was keeping a bargain I had made with myself thirty years earlier.

I first encountered The Radetzky March, one of the masterpieces of modern German fiction, while I was researching a BBC film about Vienna at the turn of the twentieth century. Its opening paragraphs promised a stirring narrative of the end of empire. Then for the next 300 pages it systematically broke that promise. I was led to expect weighty historical events distilled into the tale of a single imperial family. Instead I was taken on a wild goose chase from one provincial garrison to another in the company of officers who had nothing better to do than drink, gamble, get into debt and beguile the time with desultory affairs. Between its opening in 1859 and its final pages set six decades later almost nothing happened. There were two sexual encounters, a duel and an industrial strike, but they were all left unresolved. Even the Great War and the death of the longest surviving European monarch were brushed aside with casual disregard. It was the least epic historical novel I had ever read and I was totally seduced by it. I was captivated by its glimpses of a vanished world seen through the wrong end of a telescope and framed in dreamlike prose which kept slipping out of reach. It was elusive and ironic and it stuck like a burr in my brain.

I knew little of Habsburg history and even less of the author. I soon discovered that I was not alone. Even today there is no English biography of Joseph Roth and only a couple of academic studies, one of which is currently remaindered. His personal life is cloaked in mist. Yet the landscape he described was unforgettable and I was impatient to encounter it at first hand. I swore that one day I would follow the novels sad and confused hero Carl Joseph von Trotta along the margins of Mitteleuropa. I would drink in faded cafs across the road from crumbling opera houses. I would buy second-class tickets in Kaiser-yellow railway stations and take rickety trains from Slovenia and Moravia in the west to the dank marshes of Galicia in the east.

It was fifteen years before I could keep my promise to myself. Three decades ago the borders of Europe and Russia were still in Neville Chamberlains words a faraway country of which we know little. Then in the late 1980s the landscape of Poland, Czechoslovakia and Ukraine was radically transformed. The Iron Curtain lifted to reveal one perfectly preserved stage set after another, all painted in faded pastels the pink, green and gold favoured by Emperor Franz Joseph. Beyond the urban scenery of Mitteleuropa sat the smudged landscape of muddy plains, framed by dense wooded hills, familiar to me from the journeys taken by Carl Joseph during the novel. Much of it had scarcely changed since he crossed it with his mistress in a wagon lit just before the First World War. As I followed the railway tracks eastward through towns with evocatively unpronounceable names like Brno, Cluj and Przemysl, I could see how fifty years of communist paralysis had frozen the frame. Across the Great Hungarian Plain and through the forests of Trans-Carpathia, where farmers wearing embroidered smocks drove ox carts loaded with logs along tracks crowded with geese, I seemed to be watching a 1930s movie played in reverse. Surely now I could match Roths misty hypnotic descriptions of Galicia with the reality which inspired them. Perhaps, when I reached his birthplace, I might even be able to construct a psycho-geography of the author what German speakers call his seelenlandschaft, his spiritual landscape. But when I arrived in his homeland another promise was broken. The scenery was intact but the screenwriter had left the set.

It might have helped if I had known that I was being led through the swamps by one of literatures most prodigious liars. Joseph Roth, born in 1894 in what is now Western Ukraine and buried in the Paris suburbs a mere forty-five years later, the victim of drink and despair, lived a life as clouded and obscure as his remarkable fiction. In his diaries and letters, in his reported conversations and his confessional journalism, he scattered falsehoods like a Ruthenian peasant sowing corn. As a novelist, he constantly blurs historical truth and hallucination. As a reporter, his documentary accounts of the years after the Great War are bent out of true by his wounded subjectivity. At first glance, his sidelong descriptions of the end of three European empires seem almost cinematic. That is another illusion. If there is anything filmic about Roths work, it is its debt to the expressionist German movies which he reviewed in the smoky Berlin picture houses of the 1920s. Like the films of Murnau and Pabst and the paintings of Grosz and Dix and Beckmann, his stories belong in the world of Die Neue Sachlichkeit the new objectivity which was the house style of Weimar Germany. That term is also misleading. Groszs drawings are no more objective than Roths writing. In his published work, every phrase, each observation bears witness to the fragility of fact. His accounts of his own life are even more flimsy. Nothing stands up to close examination. His biographer David Bronsen calls him a mythomaniac. The Ukrainian scholar Larisa Cybenko prefers the term fantasist. The English literary critic Jon Hughes argues that even his narrative voice is a fabrication. In several of his stories he introduces a character with the name Joseph Roth who simultaneously acts in the drama and observes it from the edge of frame. I soon learned that the writer I had chosen as a tour guide through Eastern Europe after the fall of the Berlin Wall was a compulsive falsifier.

Consider the bald facts of his life. He was born a hundred and twenty years ago on the borders of Austria and Russia. He studied in Lemberg and Vienna and enlisted in the imperial army during the Great War. He worked as a journalist in Berlin during the Weimar Republic, in post-revolutionary Russia and in Paris when it was Europes creative fulcrum. Yet the further he travelled from his birthplace, the more his fiction returned to the eastern provinces of Franz Josephs former empire. The little Jewish town where he spent the first eighteen years of his life appears under one fictitious name or another in nine of his fifteen novels. It is peopled with deserting soldiers, Hasidic Jews, dealers in drink and contraband, human traffickers, revolutionaries, prostitutes, and all the other flotsam which drifted across Western Ukraine during and after the Great War. Most of his characters are compulsive shape-changers. Their identities are as diffuse and slippery as the surrounding marshes. Even the solid Habsburg cities where some of them settle have a history of constant flux. Between the two world wars, the regional capital of Galicia changed its name and nationality four times. When Roth was born, it was Austrian Lemberg. In 1918, during the short-lived Ukrainian Republic it was called Lviv. After the Treaty of Saint Germain it was incorporated into Poland under its old name of Lwow. When the Russians invaded in 1941 it was submerged in the Soviet Socialist Republic of Ukraine as Lvov. Almost all the eastern Habsburg cities changed their names. Tarnopol became Ternopil and Czernovitz was first Cernauti then briefly Chernovtsy, briefly Cernauti and finally Chernivtsi once again as it passed from Austria to Romania to Poland to the Soviet Union. Today these bi-polar towns are all in the Republic of Ukraine and that word contains the secret of their fluid identity. In Russian and in Ruthenian the nineteenth-century term for the local Slavic vernacular

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Wandering Jew: The Search for Joseph Roth»

Look at similar books to Wandering Jew: The Search for Joseph Roth. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Wandering Jew: The Search for Joseph Roth and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.