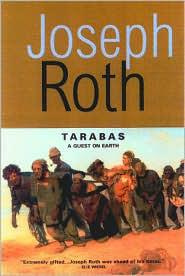

Joseph Roth - Tarabas

Here you can read online Joseph Roth - Tarabas full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2002, publisher: The Overlook Press, genre: Prose. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Tarabas

- Author:

- Publisher:The Overlook Press

- Genre:

- Year:2002

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Tarabas: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Tarabas" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Tarabas — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Tarabas" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Joseph Roth

Tarabas

PART ONE. THE TRIAL

1

IN August of the year nineteen-hundred-and-fourteen there lived in New York a young man named Nicholas Tarabas. By nationality he was Russian. He belonged to one of those races, which at that time the great Tsar ruled over, and which are known today as the western border-nations.

Tarabas was the son of well-to-do parents. He had studied at the technical college in St. Petersburg. Less actual conviction than the unfocused ardour of his young heart had led him, during his third term as a student, to join a revolutionary society which was shortly afterwards implicated in a bombing outrage against the governor of Kherson. Tarabas and his comrades were brought to trial. Some were convicted, others acquitted. Among the latter was Tarabas. His father turned him out of doors and promised him money if he would agree to emigrate to America. Young Tarabas left his native land as unthinkingly as he had become a revolutionary two years before. He followed his curiosity and the call of the far unknown, carefree and strong, and filled with confidence in a new life.

Only he had not been two months in the great stone city when homesickness woke in him. The world still lay before him, and yet it sometimes seemed as though it already lay far behind. There were days when he felt like an old man, filled with longing for his wasted life and with the knowledge that he has no time left to start another one. And so he let himself drift, as the phrase is, and made no attempt to adapt himself to his new surroundings nor to look about for a means of livelihood. He yearned for the soft blue haze on the fields of his childhood, for the frozen furrows in winter, the larks keen trilling all the summer long, the fragrance of potatoes roasting in autumn fields, the croaking songs of frogs down in the swamps, and the edged whisper of crickets in the meadows. Nicholas bore nostalgia in his heart. He hated New York, the tall buildings, the wide streets, and all else that was stone. And New York was a city of stone.

A month or two after his arrival he had made the acquaintance of Katharina, a girl from Nizhny-Novgorod. She was a waitress. Tarabas loved her like his lost home. He could talk to her; he might love her, taste her, smell her. She reminded him of his fathers fields, of the Russian sky, of the fragrance of roasting potatoes in the autumn ploughland of his childhood. Katharina was not from his district. But she spoke the language he could understand. And she understood his moods and did not thwart them. The songs she sang he too had learnt at home, and she knew people of the same kind as he had known.

He was jealous, wild, and tender, as ready with kisses as with blows. For hours together he would loiter in the caf where Katharina was employed. He would often sit long at one of her tables, watching her, the men waiters, and the customers, and sometimes he would go into the kitchen to observe the cook as well. The presence of Nicholas Tarabas began to make others feel uncomfortable. The owner of the caf threatened to dismiss Katharina. Tarabas threatened to kill the owner of the caf. Katharina asked her friend to come there no more. But jealousy drove him back again and again. One evening he committed an act of violence which was to alter the course of his life. But first this happened:

On a sultry day in late summer he went out to Coney Island, New Yorks great amusement park. He wandered aimlessly from one booth to another. He flung meaningless wooden balls at worthless china objects; with gun, pistol, and antiquated bow and arrow he shot at foolish figures and set them in foolish motion; he bestrode horses, donkeys, camels, and let them revolve with him on merry-go-rounds; seated in a boat he traversed grottoes full of mechanical ghosts and sinister gurgling waters; he enjoyed the shocks of violent soaring and descent upon the scenic-railway, and in the chamber of horrors he looked at the anomalies of nature, venereal disease, and notorious murderers. At last he stopped outside a booth where a gipsy engaged to tell the fate of those who would show her their hands. Tarabas was superstitious. He had already taken many an opportunity to cast a glance into the future; he had consulted the interpreters of stars and cards, and had himself delved into all manner of literature dealing with astrology, hypnosis, and suggestion. White horses and chimney-sweeps, nuns, monks, and priests, met in the street, determined where he should go, the roads he should take, the direction of his walks and his most trivial decisions. He was careful to avoid old women and red-haired people in the morning. And Jews who chanced to cross his path on Sundays he looked upon as certain harbingers of evil. These matters largely occupied his waking hours.

Before the gipsys tent, therefore, he stopped. The upturned barrel, in front of which she sat upon a stool, was spread with the paraphernalia of her sorcery a glass ball filled with some green fluid, a yellow wax candle, playing cards and a small pile of silver coins, a little rod of rusty-brown wood, and stars of shining gold-leaf, large and small. There was a crowd before the fortune-tellers booth, but no one had yet dared to go up to her. She was young, handsome, and indifferent. She did not seem even to see the people. She kept her brown, beringed hands folded in her lap, and her eyes downcast and fixed upon them. Her garish red silk blouse did not hide the living breath of her full bosom. Great gold coins quivered along the heavy chain wound three times round her neck. She wore similar coins in her ears. And it was as if a clink and clangor went out from all that metal, although in reality one heard no sound from it. The gipsy did not seem at all concerned to be the paid intermediary between the supernatural powers and the creatures of earth, but seemed rather to be one of those powers themselves, which do not reveal to men their destiny but ordain it.

Tarabas pushed his way through the crowd, approached the barrel, and offered his hand without a word. Slowly the gipsy raised her eyes. She looked Tarabas in the face until, his self-assurance wavering, he made a movement as though to withdraw. He felt the warmth of the brown fingers and the coolness of the silver rings upon his outspread hand. Little by little, very gently, his elbows brushing the glass ball as he stooped, the woman drew him over towards her till his face was close to hers. The people behind him pressed nearer; he felt their curiosity. That, their curiosity, seemed to be what was forcing him over towards the fortune-teller, and he would have liked to step across the tub to rid himself of them, and be alone with her. He was afraid lest she might talk about him too loudly and that they would hear and he was about to change his mind and go away again.

Dont be afraid, she said in the language of his own country, nobody will understand me. But first give me two dollars, and take care the others see you. Many of them will go away then.

It startled him that she had guessed his mother-tongue. She took the money with her left hand, held it up a while for the people to see, and put it down upon the tub. Then she spoke in Tarabass own language. You are very unlucky, sir. I read in your hand that you are a murderer and a saint. There is no unhappier fate in all the world. You will sin and atone and both upon this earth.

The gipsy released Tarabass hand. She dropped her eyes, clasped her hands in her lap, and was motionless again. Tarabas turned to go. The people made way for him, full of respect for a man who had given two dollars to a gipsy. The fortune-tellers words stood separate in his memory, without coherence; he could repeat them as they had been said to him. He wandered without interest among the shooting-booths and marvels, turned back, resolved to desert the park, thought about Katharina, whom he would soon be going to fetch as usual, remembered that he had felt her growing distant towards him lately, and tried to fight the feeling down. It was the end of August.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Tarabas»

Look at similar books to Tarabas. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Tarabas and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.