BOOKS BY JAMES A. MICHENER

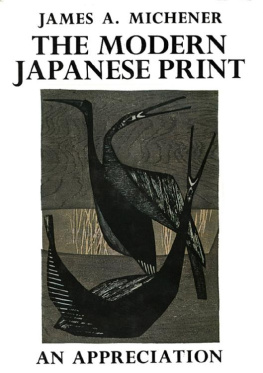

THE MODERN JAPANESE PRINT: An Appreciation

THE HOKUSAI SKETCHBOOKS: Selections from the Manga

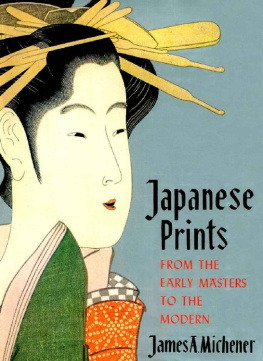

JAPANESE PRINTS: From the Early Masters to the Modern

SAYONARA

THE BRIDGE AT ANDAU

with A. Grove Day

RASCALS IN PARADISE

THE FIRES OF SPRING

HAWAII

THE BRIDGES AT TOKO-RI

TALES OF THE SOUTH PACIFIC

CARAVANS

THE SOURCE

RETURN TO PARADISE

THE VOICE OF ASIA

THE FLOATING WORLD

JAMES A. MICHENER

THE MODERN JAPANESE PRINT

AN APPRECIATION

with ten prints by

HIRATSUKA UNICHI * MAEKAWA SEMPAN MORI YOSHITOSHI * WATANABE SADAO * KINOSHITA TOMIO SHIMA TAMAMI. AZECHI UMETARO * IWAMI REIKA YOSHIDA MASAJI * MAKI HAKU

CHARLES E. TUTTLE COMPANY: PUBLISHERSRutland, Vermont & Tokyo, Japan

Representatives

Continental Europe: BOXERBOOKS, INC., Zurich

British Isles: PRENTICE-HALL INTERNATIONAL, INC., London

Australasia: BOOK WISE (AUSTRALIA) PTY. LTD.

104-108 Sussex Street, Sydney 2000

Published by the Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc.

of Rutland, Vermont &. Tokyo, Japan

with editorial offices at

Osaki Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo 141-0032

Copyright in Japan, 1968, by Charles E. Tuttle Co., Inc.

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 62-17555

ISBN: 978-1-4629-0405-1 (ebook)

First popular edition, 1968

Fourth printing, 1982

PRINTED IN JAPAN

PUBLISHERS FOREWORD

I N 1959 James Michener came to us with a unique and challenging idea. He wanted us to publish, in a deluxe format, an edition of original contemporary Japanese woodblock prints. Mr. Micheners reasons for making this request derived from his personal interest in the woodblock artists of Japan and, as he saw it then, their almost insurmountable struggle to make a living from their art.

As publishers devoted to the concept of cultural interchange between the East and West, we quickly caught Mr. Micheners enthusiasm and agreed to the project.

Then the work began. How should we determine which of the hundreds and thousands of contemporary woodblock prints might be included? We decided to sponsor a contest to be judged by a panel of qualified art experts in the United States and Japan. From a total of 275 prints submitted by 120 artists, ten were chosen as best representing the richness and power of the modern Japanese print movement. The final selection is a beautiful and significant set of prints, running the stylistic gamut from representational to abstract, from typically Japanese to international, including both great old names and newcomers who are sure to become great.

Finally, in 1962, The Modern Japanese Print An Appreciation appeared as a limited edition of 475 copies in imperial folio size. The paper was the finest of handmade Japanese vellum; the binding, three colors of pure, fine-weave hemp cloth. It is a book in which we, and the author, take considerable pride, for it is more than a book; it is a work of art.

The Modern Japanese Print met with wide critical and commercial acclaim. Now, several years later, it has been suggested that we bring out a popularly priced edition, thus displaying to a far wider audience the techniques and craftsmanship of this group of distinguished artists, along with Mr. Micheners perceptive, informative commentary.

James Michener heartily endorses this version of what originated as a collectors item. We present this volume with renewed pride.

INTRODUCTION

I N the early summer of 1959, business required that I be in Tokyo during an exciting time in my life: word kept trickling through from New York telling of the unexpected good things that were happening to a novel I had recently completed, and it looked as if it might be a success. For five years I had worked on the novel, and to have it accepted was encouraging, but the degree of success promised by these first reports went well beyond my expectation. Thus early in the life of the book I was assured that the time I had invested in its writing would be repaid; whether or not the public would like the book would be determined later.

As a result of the good news, I found myself assured of financial independence for a few more years, and I began to reflect upon how unfairly modern society distributes the rewards of art. I knew literally hundreds of able writers who found it impossible to earn a living, while to a few all good things happened. Once I myself had labored at writing for eight years without being able to earn a nickel, and I had been as good a writer then as I was now. Those who try to be artists exist in a world of nothing or everything, and I wish it were not so.

It was in this mood that I was drifting down Tokyos Ginza one sunny afternoon, idly watching the flow of life along that enchanting thoroughfare. With nothing better to do, I turned west and passed into the warren of little streets and alleys known as the Nishi Ginza. Soon I found myself standing before a window I had grown to know; it belonged to the print shop and art gallery called Yoseido, opened in 1954 by Abe Yuji, third-generation representative of a family of art-mounters which had formerly been appointed to mount scrolls, screens, and the like for the Imperial Household and had also become prosperous in Ginza real estate. Ever since Yoseidos opening, the artistically-minded young Abe had served as the principal salesman for a group of artists who had made something of a splash in the art world.

I entered Yoseido that afternoon and saw on its walls the latest prints by artists I had come to know well. Here was a brilliantly colored alpine scene by Azechi Umetaro, and I studied the manner in which this delightful mountaineer had progressed to new understandings of his art. On the other wall was a marvelous, somber abstraction by Yoshida Masaji, a brooding thing of gray and black and purple, and again I lost myself in contemplating the various plateaus of progress across which this young man had moved in the years I had known him.

Also prominent was a large print in stark black and white, an architectural scene carved in the most ancient tradition by the oldest of the artists, little Hiratsuka Unichi, who had been my close friend for many years and who was still one of the greatest of contemporary woodblock artists, regardless of what country one was considering.

Here before me was the work which fifty men had accomplished in the two years since I had last met with them: the scintillating color prints, the vibrant black-and-whites, those done in the old style, and those so modern that they clawed at the mind for recognition. It was a body of magnificent work, one groups summary of how men saw the world and its passions.

As I looked at the prints I could see behind each one the man who had carved those blocks and pressed that paper down into the splashed colors. They were as fine a group of men as I have ever known: schoolteachers, mechanics, intellectual hermits, wild, gusty men who loved to drink, mountaineers, factory workers, poets of the most exquisite sensibility, laughing men, sober men, tragic men. And as I saw their faces staring back at me I experienced a real sickness of the soul, and out of that sickness came this book.

For I, by pure accident, worked in a field (writing) in a society (America) that assured me a decent income, a good living, and some security for the future. But those men on the wall, most of them with a far greater talent than mine, were laboring in a field (print-making) in a country (Japan) that provided only the most meager living, if any. Of all the woodblock artists I have known in Japan only two have been able to make a living from their art, and they have worked like dogs to accomplish even this. All the others have had to devote their principal energies to irrelevant jobs.

Next page