CHAPTER ONE

Healing Waters

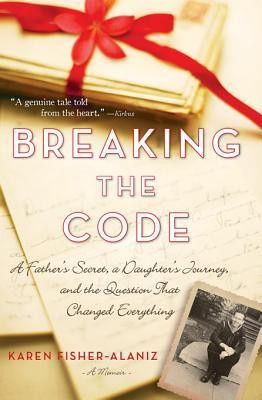

Well, here we are but where are we going? That is the question.January 9, 1945

He stood at the end of the pier watching the petals drift out to sea. He leaned on his cane. No longer the young sailor hed once been, he was an old man now, something his comrade, his friend, never got to be. The red and white petals followed an unseen path, becoming tiny specks in a vast oceanan ocean that, during the war, held only sorrow and loss. But now those same waters were a place of healing.

Never good-bye, he said softly. Never good-bye.

CHAPTER TWO

A Line in the Sand

Its sure tough alright but its going to be worth it. Ive learned more about the Navy in the past two days in the barracks room lecture than in two months at home.April 28, 1944

I always knew my father had been in a war. But as a child it was of little importance to me. I had bicycles to ride, friends to play with, and trees to climb.

He would tell us stories about the war. He was in the Navy and stationed at Pearl Harbor a few years after it was bombed in 1941. He spent his days working in an office. On liberty, he went to the movies or exploring with friends. These were the stories he told, which were never terribly interesting. And although he didnt tell them on a regular basis, during our childhood years, my sisters and I heard each one many times.

It would always begin the same waywith something that sparked the memoryand then the retelling would begin. The details never changed. His memory never wavered. Each story had a beginning, middle, and end.

My sisters and I, all born years after the war, must have had some innate sense that these stories were important, even sacred. Following my mothers lead, we stopped whatever we were doing to listen. We didnt interrupt or ask questions. We never informed him that wed heard this one before.

When he got to the end, he would simply go back to what hed been doing. Then weeks, months, and even years would pass without a single story being told. If Id ever written them down, Im sure there would have been only eight or ten stories overall. New stories were never added.

In my teens, my patience for the repeated stories ran out. When I heard a story coming, I looked for the nearest exit. I rolled my eyes or sighed loudly, hoping hed get the hint. He never did. Once the story began, nothing could stop him from finishing it. To me, the stories were just that: stories, ancient history. I filed them away with the stories of my grandfather walking to school in a blizzard. They were irrelevant, intangible. As I got older, he told them less and less.

What I didnt know then was that the stories he told werent the whole story at all. They were an abbreviation. He told the version that fit comfortably into his middle-class lifethe version where everyone lived happily ever after. But more than anything, he told the version that didnt hurt and didnt require answering questions. The rest of the story, the whole and true story, would have remained untold. But one day, many years later, in a single moment, everything I thought I knew about my fathers war was turned inside out. We didnt know it then, but it was the first step on a long journey wed take together.

April 27, 2002, was my fathers eighty-first birthday. We gathered at my parents housethe small, but sunny home Id grown up infor the party. Our family is small and most of us live in the same small town. When were all together, we take up the three comfortable chairs (recliner reserved for Dad), one sofa, and the hearth in front of the fireplace; a few kids sit on the carpeted floor. Although the house has gone through many transformations, one of which was the floor-to-ceiling brick fireplace, my father never seemed to change.

He had looked virtually the same all of my life. The only thing that changed was the color of his now gray hair, and probably the prescription for his eyeglasses. He was one of those people that you go to high school with and then see thirty years later and they truly havent changed; theyve just gotten a little older.

After dinner, as everyone settled into comfortable conversation, Dad slipped away. A few minutes later, I looked up to see him in the middle of the room. With a nod of his head, he gestured away from the crowd. I looked around to see who he was nodding at but quickly realized he was looking at me.

No one seemed to notice when, in the midst of his celebration, we went to the sunroom just two steps down from the living room. The cathedral windows that let light pour in from three sides, coupled with my mothers abundant house plants, made it feel more like an atrium. Dad sat on the curved sofa that hugged one corner of the room and patted the seat next to him. When I sat down, he placed two binders on my lap, one black and one blue.

Whats this? I asked.

Letters, he said. I wrote them to my folks during the war. You can throw them in the garbage or burn them if you want. I dont care.

Dad! Why would you say that? I asked.

He didnt answer.

I opened one of the two-ring binders to find letters written in my fathers notoriously tiny handwriting. I skimmed them and asked a few questions. But no matter how general the question, my father had no answer. I read aloud, a line or two at first and then a whole paragraph.

I wrote that? he asked. I dont remember writing that.

With that, he quietly but firmly drew a line in the sand. He was on one side; I was on the other. My questions unanswered, I wanted to implore, What is this? All these years youve had these and you didnt tell me? Why? Tell me now. Tell me everything. I stepped over the line cautiously, looking into his eyes, but then I backed up in silence, deafening silence. I retreated to the other side of that line. And then he bowed his head and walked away.

Alone that night, my family sleeping peacefully, I sat in near darkness. Only a small table lamp with beaded fringe illuminated the notebooks on my lap. I ran my hand across the weathered notebooks and cried. I cried for what I didnt know. I cried for all the times I didnt care and didnt listen. And I cried for the years those letters remained tucked away. Why had he kept them a secret for more than fifty years? There had to be a reason.

About six months prior to his birthday, he had become depressed. He seemed to be driven to watch war movies that were more and more graphic. Bookshelves were filled with WWII books hed read, often in one day. It was then that I began asking him questions about the war. All he told me were the same stories Id heard before. But now I wondered about these letters. Was there something in them that he wanted me to know?

I opened the notebook and began reading. The first letter was from boot camp in Farragut, Idaho. Every letter began with the same salutation, Dear Folks.

Next page