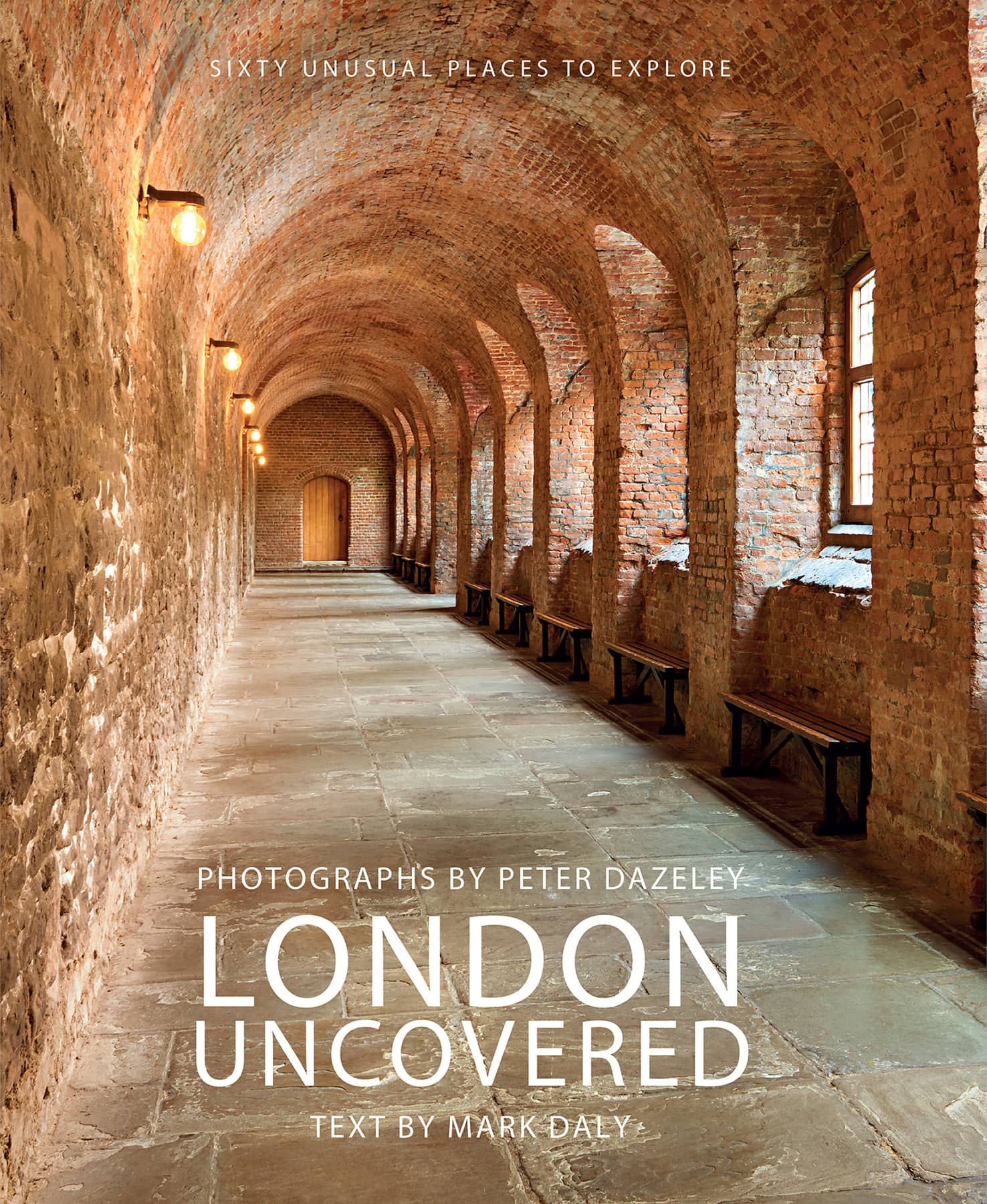

The sixty-or-so sets of images in this book are collected together under the title London Uncovered. They are places brought to life by the creative eye and searching mind of Peter Dazeley, celebrated photographer and lifetime Londoner. Uncovered does not mean the disclosure of a private place, because these buildings and sites are all available to visit without special insider access. The common thread throughout is largely the photographers ability to uncover a fresh perspective on a special piece of London. The subjects are eclectic, encompassing buildings, monuments in plain sight and walks, with some places famous and others obscure.

Two of the museums pictured are free to enter; the others have entrance charges, as do the historical homes. At the two pubs described here it is customary to buy a drink. Theatre visits will generally require tickets, although some of them offer pre-planned organised tours when performances are not running. Similarly, it is possible to see more areas of the Inns of Court by making an enquiry and pre-booking. It should not be difficult to see inside the places of worship photographed here, while respecting of times and days of worship and observing the protocols required of visitors.

Typical of the locations that possess a grand public profile but whose interiors are rarely explored is the St Pancras Renaissance Hotel. Its Grand Staircase is the centrepiece of a Victorian building brought back from the brink. Originally known as the Midland Grand Hotel, it was a wonder of the late Victorian age when it opened in 1873. Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, designer of the Albert Memorial, was the architect, and his design incorporated hydraulic lifts, speaking tubes, electric call bells, dust chutes and fireproof concrete floors.

The Grand Staircase of the St Pancras Renaissance Hotel, restored according to the scheme of 1901. Figures representing the virtues Industry and Temperance flank the arms of the Midland Railway.

The Midland Grand prospered through the Edwardian age but fell into decline after the First World War. As modern hotel standards improved during the 1920s, one of its main weaknesses the lack of bathrooms became more apparent. Few of the 250 bedrooms, heated by coal fires, had attached bathrooms, and public taste was generally turning against Victorian style. In 1933 the Chairman of the LMS Sir Josiah Stamp told architects that the building, while magnificent, was completely obsolete and hopeless. It closed as a hotel two years later. Afterwards known as St Pancras Chambers, it lingered in a long eclipse as offices for the LMS and its successor British Railways.

In the 1960s St Pancras Station lost some of its long-distance services and there were plans and proposals to close both the station and St Pancras Chambers. A rediscovery and growing regard for Victorian architecture in Britain, and a preservation campaign, won Grade I listing status for both the station and the hotel. British Rail finally moved out in 1985, but subsequently, with English Heritage, it restored the exterior and made the structure weatherproof. Except for visits by special groups, and use as a filming location, the building was empty through the 1990s.

The decision to make St Pancras the destination for international trains unlocked the future of the hotel building. The massively rebuilt St Pancras International started to receive Eurostar trains in 2007, and the restored St Pancras Renaissance opened in March 2011.

The St Pancras Renaissance Hotel is typical of Londons monuments, undergoing many transformations and renewals. Perhaps the most dramatic example of this is Cleopatras Needle on the Victoria Embankment. This ancient obelisk stands high beside a road which did not exist until 1869. It defies the classic layer-by-layer history of London, where the deeper you dig, the older you find. Even the name Cleopatra is misleading. Guidebooks give it little ink, and traffic flowing along the Embankment makes it a noisy place. Yet the obelisk is breathtakingly ancient, older than any of Londons fixed outdoor relics, such as the remaining sections of Roman wall, built in AD 200. It predates this by 1,600 years, being one of a pair erected in Heliopolis on the instructions of Pharaoh Thutmose II.

At some time after Egypt became a Roman province, the obelisks were shipped to Alexandria and re-erected at the Caesareum temple, built for Cleopatra, which is the closest justification that can be made for its future name. By then, the columns had travelled almost 750 miles from the place they were quarried. At some later time, the obelisks toppled, long after all understanding of Egypts hieroglyphic forms was lost. When the fallen obelisks were eyed with interest by British army officers in Egypt after battles against the French in 1801, a subscription was raised to pay for transferring one of the pillars to Britain. After decades of negotiations and failed attempts, it was finally shipped to Britain at great expense in 1877.

The 186-tonne Cleopatras needle is undeniably a moveable object, and for this reason London antiquarians seem to pay it little attention, but a visitor with imagination can examine the plaques around its base and marvel a little how an artefact with a timeline longer than that of the Parthenon came to embellish a Victorian civic works project.

A visit to Isabella Plantation, another fascinating yet underappreciated outdoor location, requires more careful timing. Approaching this fenced enclave, a visitor might form the impression that it is not a public place at all, but it is open from dawn to dusk around the year. It lies completely encircled within Richmond Park, which is itself the biggest enclosed space in London, and is the largest of the eight Royal Parks. The plantation has the feeling of being a secret wooded valley, peaceful and secluded even as airliners bound for Heathrow pass slowly overhead. It can claim to be the most colourful place in London, and late April or early May are best the times to see the display of flowers; the photograph here was taken during the month of May. For the enthusiast, the National Collection of azaleas introduced to Europe from Japan by plant hunter Ernest Wilson is a special attraction. There are ancient oak pollards, 400 years old, predating the 1637 parkland enclosure. Wildlife abounds.

This highly decorated first-floor curved corridor has been restored to retain the Victorian character.