The coopers shop at the Ram Brewery in Wandsworth.

The fifty or so London buildings collected in the following pages are the eclectic vision of celebrated photographer Dazeley. At least forty of them are in use, doing the job they were always designed for. Most of them stand in plain sight, and some of them are open to the public although not always the parts in the shown in the photographs. Included here are examples of industrial archaeology, historic sites, highly functional working technology, relics, structures ugly and beautiful, monumental and mean. They are coupled together under loose categories, but they can all, for various reasons, be described as unseen.

Only two Kidderpore Reservoir and the military bunker known as Paddock are completely hidden underground, showing no surface traces. Also hidden, derelict and below street level is the Roman bathhouse at Billingsgate, which is an ancient monument and the oldest structure in this collection.

Other locations, such as Tower Bridge and the Thames Barrier, are unseen because it is far from obvious how their inner mechanisms work, and the concealed parts are as fascinating as the visible structure.

Buildings in transition, whose metamorphosis is not complete, represent another category. At the time of writing, Midland Bank and BBC Television Centre, the former Naval and Military In and Out Club building, and possibly Battersea Power Station, are examples of this, while Alexandra Palace remains in a kind of limbo. In these cases, it cannot be said exactly what the future shape of these places will be.

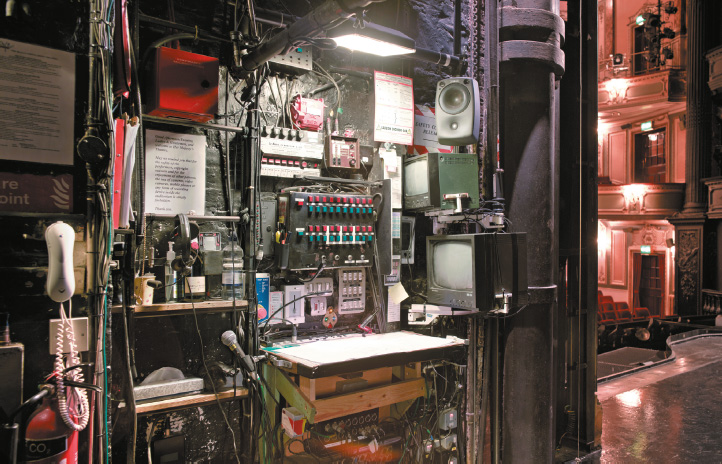

Three sporting venues and three West End theatres included are easy to access for paying visitors, but the unseen emphasis here is on the backstage, understage and technical areas. The old technical parts of London theatres are a subject in themselves: the lifting and rotating stages powered by the London Hydraulic Power Company are among hundreds of machines across the city driven by this lost power system. The same system provided reserve power for Tower Bridge.

The New West End Synagogue and St Sophias Greek Orthodox Cathedral have remarkable interiors that are hidden in the sense that their exteriors give little clue as to their magnificence. The respectful visitor should not find it too difficult to see the religious buildings included here, and in these cases it is a matter of being aware of days of worship and checking first.

Buildings that have changed purpose, whose appearance does not match their current function, include County Hall, City of London School, the Old Royal Naval College at Greenwich, the Daily Express Building and AIR Studios, all of them relatively recent conversions. County Hall is an excellent example of how new uses can be found for even the largest and most uncompromising of buildings. This successful development, taken together with what was done with Tate Modern formerly Bankside Power Station provides a great inspiration for what might be achieved at Battersea Power Station, possibly Londons most intractable disused building.

The old coppers at the Ram Brewery in Wandsworth, soon to be redeveloped.

Another south London building in metamorphosis is the Ram Brewery at Wandsworth, shown here. It used to be owned by Youngs, who always claimed that it was the oldest British brewery in continuous operation, being able to trace its history back to the sixteenth century. The yellow brick complex on Wandsworth High Street and alongside the River Wandle closed in 2006. It had always maintained traditional brewing practices, retaining steam engines in the brewery, and maintaining a stable of dray horses for local deliveries right up until the end. The cooperage shown here is a marvellously evocative place, with rows of circular cast-iron columns supporting fish-bellied beams. The tun room has a spectacular pair of coppers manufactured by Pontifex & Wood, Shoe Lane, London, dated 1869 and 1885. Much of this is expected to be preserved when the Ram Brewery site is redeveloped.

Some of the buildings in Unseen London are classic tourist destinations open to visitors, but the particular spaces and areas of buildings shown may not be open. It should always be a matter of checking first before visiting, and remember that photography may not be permitted. For some of the buildings described here, no public access is permitted and site security is strictly maintained. Open House London provides an opportunity to see many architectural secrets in a range of Londons modern and historic buildings that are not routinely open. Its annual Open House Weekend takes place in September.

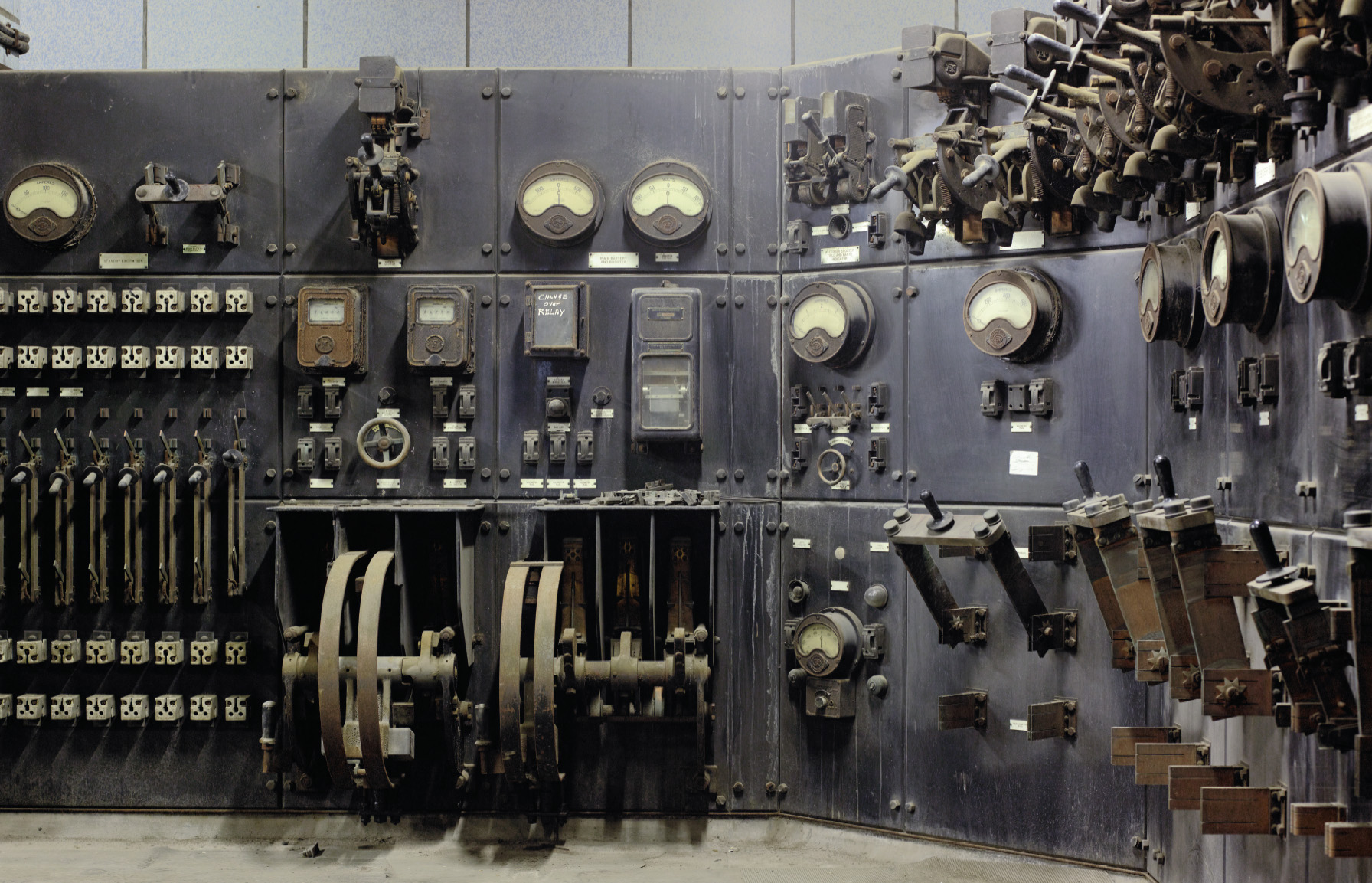

Monumental switchgear, Control Room B side, Battersea Power Station.

The jagged profile of Tower Bridge is the very symbol of London and the least secret location in the city. Its neo-gothic faades of Cornish granite and Portland stone evoke a Scottish castle, but are built on a steel frame. Much of the original operating system for Tower Bridge still exists some of it concealed, some on show, all of it solid, advanced Victorian engineering.

Tower Bridge was intended to improve road transportation to serve developments to the north and south, while allowing ships access to the many wharfs and warehouses that lined the River Thames as far as the arches of London Bridge which for most vessels was the practical limit for upstream navigation.

Bascule chamber under the south pier (tower) of bridge. Below this chamber lie the steel caissons, which made the digging of the foundations possible, and above the operating machinery, including two accumulators.

A road crossing to the east of the city was needed to ease Londons truly awful traffic problems, particularly on London Bridge. The new bridge had to be suitable for horse-drawn traffic and pedestrians, so could not be steeply graded. After years of debate and a competition, a design by architects Sir Horace Jones and engineer Sir John Wolfe Barry was selected. And after eight years in the building, Tower Bridge was completed in 1894.