Auditorium from the stage, Harold Pinter Theatre.

Foreword

by Mark Rylance

In a theatre you need to hear the truth. In a cinema you need to see it. This is not to say that the visual and auditory experiences arent an important part of each medium. People dont realize the importance of the wonderful voice in the appeal of a successful film actor like George Clooney because one is so captivated by the expression of thought and emotion in his eyes. But, in a theatre, no one can get as close as a camera, many are more than ten rows away, so the actors eyes are distant. The thought and emotion need to be heard in the voice. The eyes are important in the theatre but at distance the body even more so. A quiet voice in film and a still body in the theatre are very effective, as they allow the audience to focus on the most powerful storyteller of each discipline. Contrast, focus and contradiction are everything in acting.

Also, when many of the beautiful theatres in this book were built, theatrical lighting was far less powerful than it is today. You will see that most lighting fixtures, sockets, brackets and poles are not part of the original design. Nowadays they often crowd out the all-important private boxes that connect the auditorium with the stage. Footlights and such would have given some visual dominance to the actors, but nothing like the blazing stage we now witness, or darkened auditorium.

Some of these theatres will have employed gaslight, which, I presume, while an audience was present, could only be turned down in the auditorium, never extinguished. Everyone remained visible. Actors used make-up to strengthen their facial expressions, but really until the designer Edward Gordon Craig added a third dimension to scenery, there was only so much an actor could visually do in front of a painted canvas. So we clap our hands and make funny noises when we first walk out onto a stage, any stage, to check the acoustics. I also look up at the ceiling.

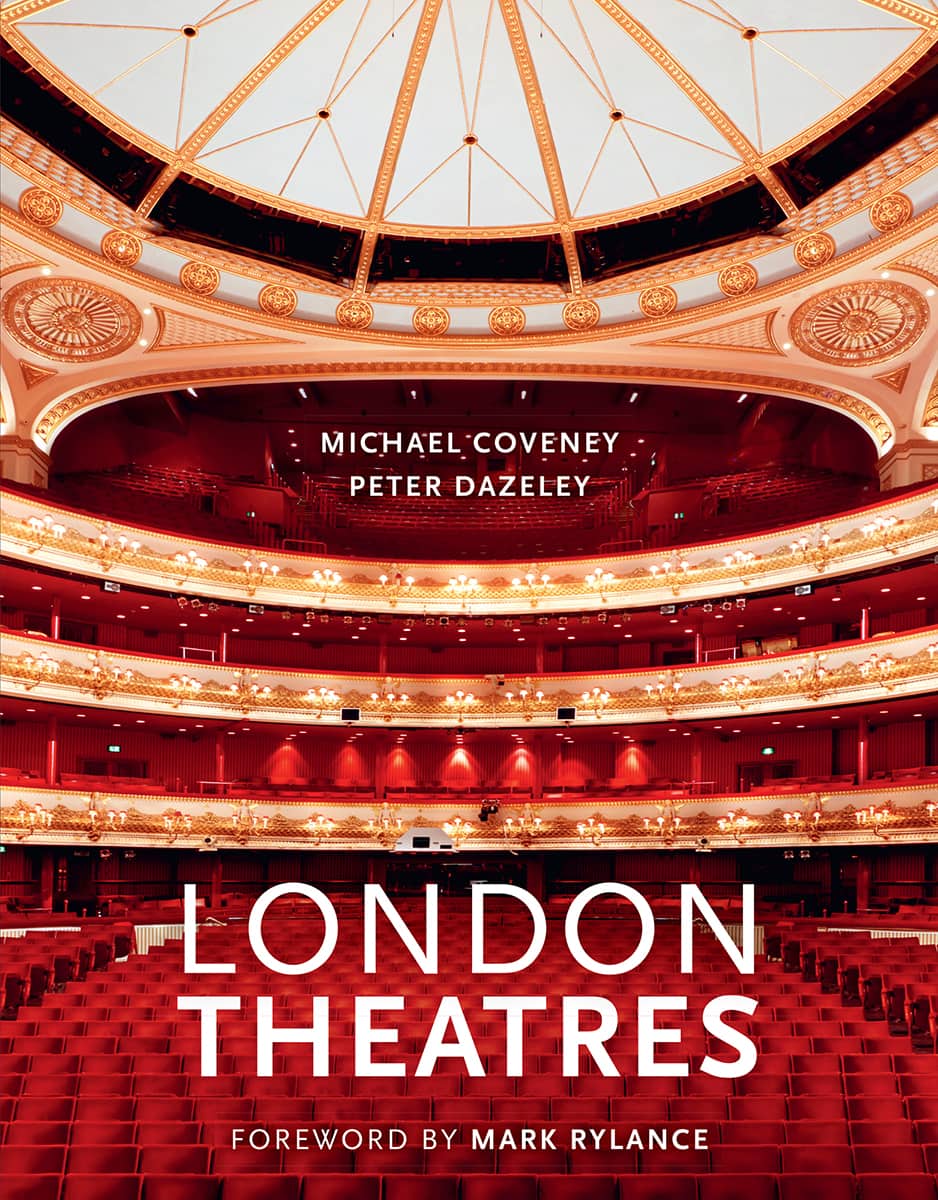

In my experience, the best of these old theatres always have some circular device in their ornate ceiling. I once toured Hamletto eleven different cities in Britain, playing all the old theatres: the Kings in Glasgow, the Palace in Manchester, the Olympia in Dublin. I learned to look up as soon as I arrived on Monday morning and, when I saw a circular pattern above the auditorium, I knew we would be all right that week. You will see a few in this book. If there wasnt a circle, I knew we would have a difficult time. It wasnt just that the acoustics were probably problematic but it was going to be harder to convince the audience that they were in the same room with us. We would be unconsciously perceived to be masters at the head of the table and they passive diners down the sides. There is no top or bottom to a circular table or room. There is a centre and a circumference. The centre is invisible and the circumference visible though its measurement forever irrational. I love all the theatres in this book, but I feel the greatest theatres always have the irrational curve of a circle in their seating and design. Why?

Most years I go walking in the mountains with my brother and a group of friends. When we light a fire at sunset, we roll rocks around to sit on and intuitively create the earliest storytelling theatre known to man. The centre is where the heat is and that heat spreads fairly to each walker sat round in a circle, as do the stories of the days sights, the jokes, hopes and remembrances, the songs, and sometimes the dance, more to keep warm, I must confess, than to represent any dying fawn or lovesick swan. There is a shared experience. Someone contributes to the story just as someone contributes logs to the fire. The fire and story both share the centre. Our faces are lit alike by the imagination and the red glow of the flames.