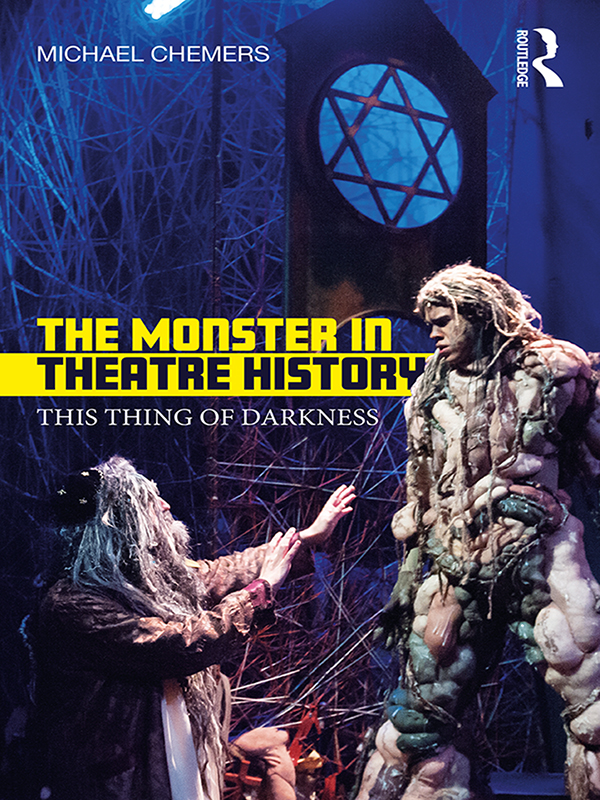

THE MONSTER IN THEATRE HISTORY

Monsters are fragmentary, uncertain, frightening creatures. What happens when they enter the realm of the theatre?

The Monster in Theatre History explores the cultural genealogies of monsters as they appear in the recorded history of Western theatre. From the Ancient Greeks to the most cutting-edge new media, Michael Chemers focuses on a series of key monsters, including Frankensteins creature, werewolves, ghosts, and vampires, to reconsider what monsters in performance might mean to those who witness them.

This volume builds a clear methodology for engaging with theatrical monsters of all kinds, providing a much-needed guidebook to this fascinating hinterland.

Michael Chemers is an Associate Professor of Theater Arts at the University of California Santa Cruz, USA.

First published 2018

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2018 Michael Chemers

The right of Michael Chemers to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright-holders. Please advise the publisher of any errors or omissions, and these will be corrected in subsequent editions.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been requested

ISBN: 978-1-138-21089-9 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-21090-5 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-45409-2 (ebk)

In Memoriam: Gene Wilder (19332016) for bringing a loving Frankenstein full circle

Mike Carey

Monsters have always been with us, but in the modern world they are an obsession. It has never been easier to make one or to become one. In that sense, as in a great many others, this book feels both timely and topical. It is also, it must be said, so vast in potential scope that it curves around to embrace and engulf much of our shared culture and our social discourse.

Faced with a potentially infinite frame of reference, Michael Chemers has chosen as his central focus monsters in theatrical performance. When a monster is not merely discussed or represented but performed, he tells us in his prefatory remarks, it enters [an] embodied realm. Performance, seen from this point of view, is different from other creative endeavours because it summons the monster into our presence, into the physical space we occupy, and thereby makes possible an imaginative and emotional confrontation that is often lost or evaded in other narrative contexts.

I found myself thinking, as Michael defined his terms of reference and set out his analytical tools, of a performance of The Tempest I saw in London ten years ago, directed by Rupert Goold. Goolds Prospero was vividly and poignantly portrayed by Patrick Stewart, but it was Julian Bleachs Ariel that electrified me. Summoned by his master, he rises out of a garbage bin in which a fire has been set and rises, and rises, and continues to rise, until he towers over Prospero and has to lean down, bending in what seem to be all the wrong places, to hear his commands.

Normally, when The Tempest is performed, Ariel is not the monster. Here he was most definitely monstrous, and as such he became the walking, talking representation of the moral compromises Prospero has made for his art, for his power. The terrible temptation that he eschews when, at the end of the play, he chooses to break his staff and drown his book. Ive never thought of the play the same way since. That performance irrevocably changed the conceptual terrain for me.

So I welcome and feel as though I will greatly profit from a critical investigation that leans upon the performative aspects of monster narratives.

I should offer a disclaimer at this point. My own professional experience almost completely excludes performance (the almost in that sentence representing two radio plays and a movie screenplay). I do have a good working knowledge of monsters, though. For a long time I lived on intimate terms (one script every four weeks for seven years) with the fallen angel, Lucifer, and in The Unwritten, again collaborating with artist Peter Gross, I introduced the Creature from Mary Shelleys Frankenstein as a regular supporting character. Its this more recent experience Id like to offer up here, with a view to illustrating one or two of the key arguments of this fascinating and invaluable book in a sphere other than the theatrical.

The Unwritten is a story about a man, Tom Taylor, who fears he may be someone elses fictional character. Frankensteins Creature seemed to me and Peter to be the perfect foil for Tom because of his very turbulent relationship with the man who made him. Even more than Lucifer he was the rebel whose biggest ontological burden was his own origin a fictional creation who could stand, metatextually, for any invented character who has a quarrel with his creator, including our own much put-upon protagonist.

We were aware that in doing this we were twisting the character away from the dense and powerful network of metaphors that define his meaning in the novel. But we had the very best of intentions. One of our goals, which we never got to achieve, was to introduce the original Creature (or our version of him) to his underachieving twin brother, the shambling pre-verbal nebbish from James Whales 1931 Hollywood movie. We had a point to make about how monsters can sometimes be emasculated and robbed of their subversive power when their story falls into the hands of huge commercial corporations with a vested interest in the status quo.

Universal werent the only ones to get Frankenstein badly wrong. My own musings on the subject started at the age of seventeen when I came across a copy of Kingsley Amiss New Maps of Hell in my school library and read it from cover to cover. I was already addicted to speculative fiction in all its forms, and I was thrilled to discover that someone had taken on the task of writing a historical and thematic study of science fiction, linking the genres current practitioners to their great forebears.

For the most part I thought Amis did a solid job of teasing out the social and technological concerns underlying the sci-fi of the post-war years. But even as a teenager with all the critical understanding and discrimination of the average prawn I could see that Amis had hit a reef when it came to Mary Shelleys Frankenstein.

Frankenstein, Amis wrote, in the popular mind, when not confused with his monster, is easily the most outstanding representation of the generic mad scientist who plagued bad early-modern science fiction. This is about as wrong as its possible to be. In defining Shelleys novel as a cautionary tale about the overweening presumption of science, Amis completely misses her uncompromising social message. As Michael Chemers forensically argues in this volume, Shelley does not locate Victor Frankensteins tragic flaw in his recklessly taking on an aspect of Gods creative power. On the contrary, his imagination and ambition are his foremost claims on our imaginative sympathy. Its through his inability to recognise and embrace his responsibilities to the life form he has created that he brings about his own downfall.