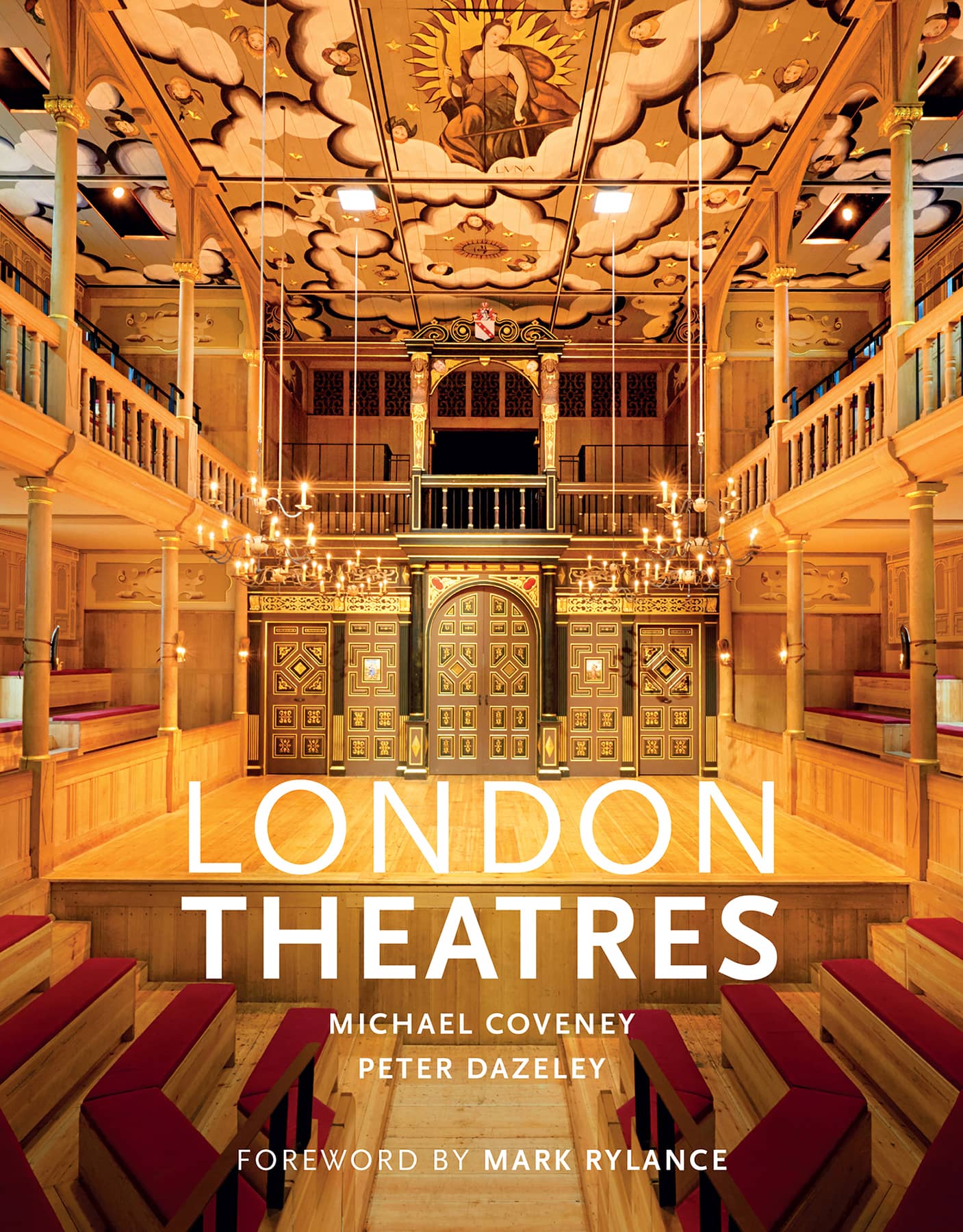

View from the back of the stage, Theatre Royal Stratford East.

LONDON

THEATRES

MICHAEL COVENEY

PETER DAZELEY

FOREWORD BY MARK RYLANCE

Foreword

by Mark Rylance

In a theatre you need to hear the truth. In a cinema you need to see it. This is not to say that the visual and auditory experiences arent an important part of each medium. People dont realize the importance of the wonderful voice in the appeal of a successful film actor like George Clooney because one is so captivated by the expression of thought and emotion in his eyes. But, in a theatre, no one can get as close as a camera, many are more than ten rows away, so the actors eyes are distant. The thought and emotion need to be heard in the voice. The eyes are important in the theatre but at distance the body even more so. A quiet voice in film and a still body in the theatre are very effective, as they allow the audience to focus on the most powerful storyteller of each discipline. Contrast, focus and contradiction are everything in acting.

Also, when many of the beautiful theatres in this book were built, theatrical lighting was far less powerful than it is today. You will see that most lighting fixtures, sockets, brackets and poles are not part of the original design. Nowadays they often crowd out the all-important private boxes that connect the auditorium with the stage. Footlights and such would have given some visual dominance to the actors, but nothing like the blazing stage we now witness, or darkened auditorium.

Some of these theatres will have employed gaslight, which, I presume, while an audience was present, could only be turned down in the auditorium, never extinguished. Everyone remained visible. Actors used make-up to strengthen their facial expressions, but really until the designer Edward Gordon Craig added a third dimension to scenery, there was only so much an actor could visually do in front of a painted canvas. So we clap our hands and make funny noises when we first walk out onto a stage, any stage, to check the acoustics. I also look up at the ceiling.

In my experience, the best of these old theatres always have some circular device in their ornate ceiling. I once toured Hamlet to eleven different cities in Britain, playing all the old theatres: the Kings in Glasgow, the Palace in Manchester, the Olympia in Dublin. I learned to look up as soon as I arrived on Monday morning and, when I saw a circular pattern above the auditorium, I knew we would be all right that week. You will see a few in this book. If there wasnt a circle, I knew we would have a difficult time. It wasnt just that the acoustics were probably problematic but it was going to be harder to convince the audience that they were in the same room with us. We would be unconsciously perceived to be masters at the head of the table and they passive diners down the sides. There is no top or bottom to a circular table or room. There is a centre and a circumference. The centre is invisible and the circumference visible though its measurement forever irrational. I love all the theatres in this book, but I feel the greatest theatres always have the irrational curve of a circle in their seating and design. Why?

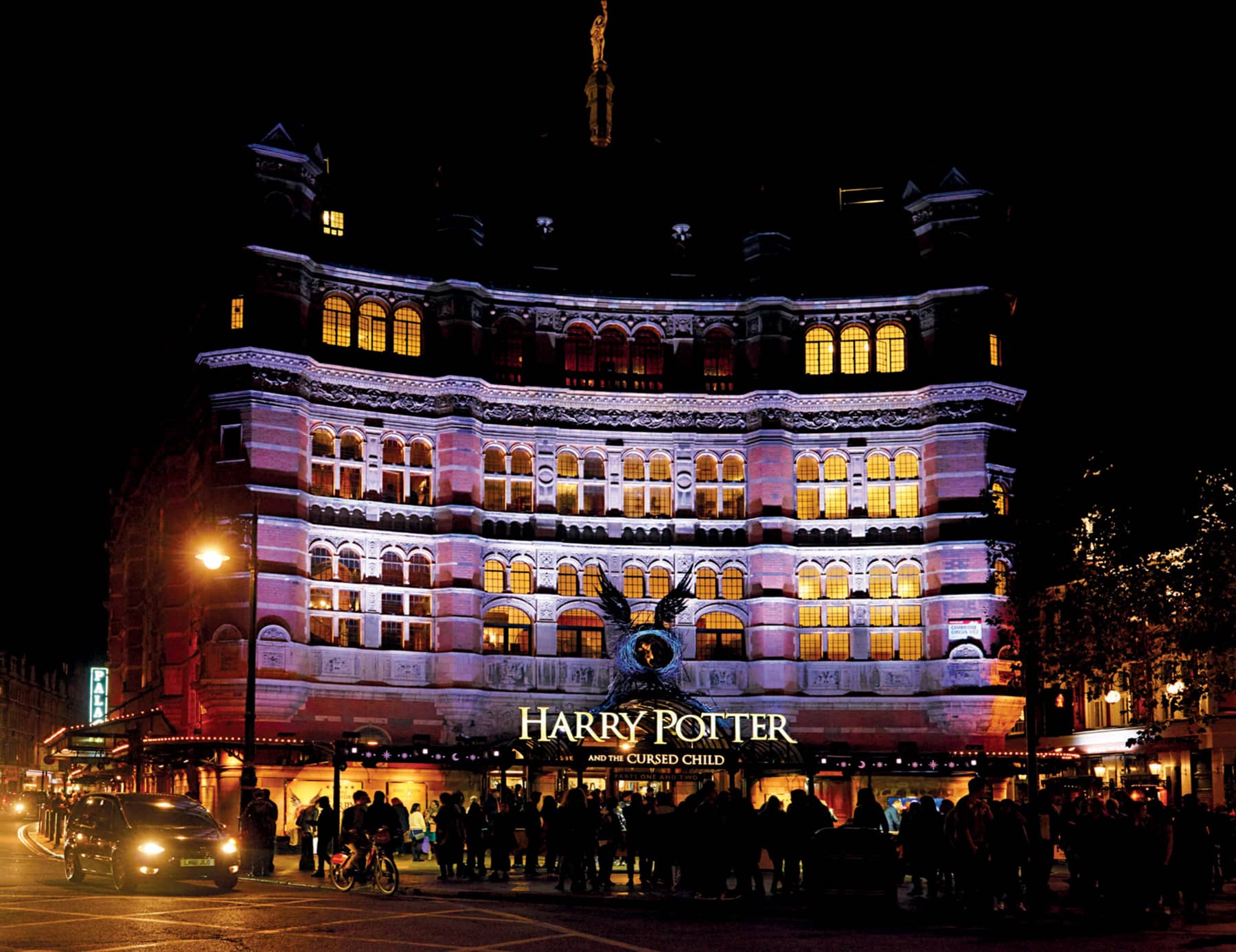

Most years I go walking in the mountains with my brother and a group of friends. When we light a fire at sunset, we roll rocks around to sit on and intuitively create the earliest storytelling theatre known to man. The centre is where the heat is and that heat spreads fairly to each walker sat round in a circle, as do the stories of the days sights, the jokes, hopes and remembrances, the songs, and sometimes the dance, more to keep warm, I must confess, than to represent any dying fawn or lovesick swan. There is a shared experience. Someone contributes to the story just as someone contributes logs to the fire. The fire and story both share the centre. Our faces are lit alike by the imagination and the red glow of the flames. I love how many of these theatres choose red for the colour of their seats, as if conscious of their great-grandfather, the primeval fire! Of course they are not theatres in the round, such as Shakespeares Globe. They are not even the semi-circle of a Greek amphitheatre, such as the Olivier at the National Theatre, but they havent forgotten their past. Their fire curtains give them away.

I was asked to write something about how you play these theatres. I learnt the most from Giles Havergal, who gave me my first job at the Citizens Theatre, Glasgow, and from my time at the newest old theatre in this book, Shakespeares Globe. On most evenings, Giles instinctively stood at the front of his theatre with the humblest employees, the ticket-takers, welcoming the audience as if they were part of his company. His directors office was located beside the stalls, front of house, and we often saw him backstage in the staff dining room or rehearsal room. Everything was contained within that one old building, and the crown touched the feet so to speak; the governor walked amongst us, all of us, knew us all by name. I relate this tangential history of Mr Havergal as he seems to me always to have been the finest director of a theatre I have ever encountered, because he made a true circle of the audience and artists, inspired I propose by the architecture of his old theatre.

Shakespeares theatre inspired me alike, but on stage as well as off. Unable to turn off the sun in the daytime I saw my audience for the first time. Saw, for the most part, their innocence and willingness for the play. In the dark I had projected onto them my own criticism and disbelief. Thrust, on the Globe stage, into the middle of the circle of shared light, in an age before steel allowed the architects to throw forward the galleries and push the actors behind a proscenium, I realised the single most important lesson I have ever learnt as an actor. I must play with the audience, not at them, for them or to them with them, with their imagination, as fellow players. I was amongst them, part of a circle, a storytelling circle. They were at the same table, in the same room, around the same imaginative fire of whatever story we had lit.

This lesson served me well in all other theatres since. It is why I object to lighting and sound equipment occupying the boxes of West End theatres rather than people. I have it in my contract that the boxes must be used for the audience, so that the audience and actor can be seen together, completing the circle. Dont get me wrong, there are many aspects of modern technology that thrill me in the theatre, but the old theatres remind me that unless used carefully, technology can divide the room and remove the actor to another place. Impressive and powerful as that may be, the greatest moments for me, as actor or audience, have been when actor and audience have become one. That is what I go to experience in all these wonderful theatres.