Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2015 by Scott L. Hoffman

All rights reserved

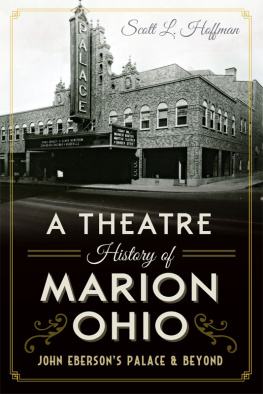

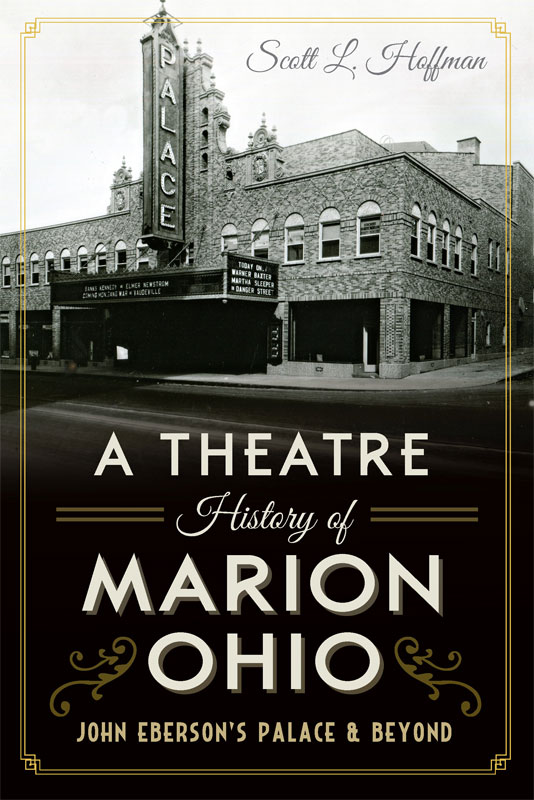

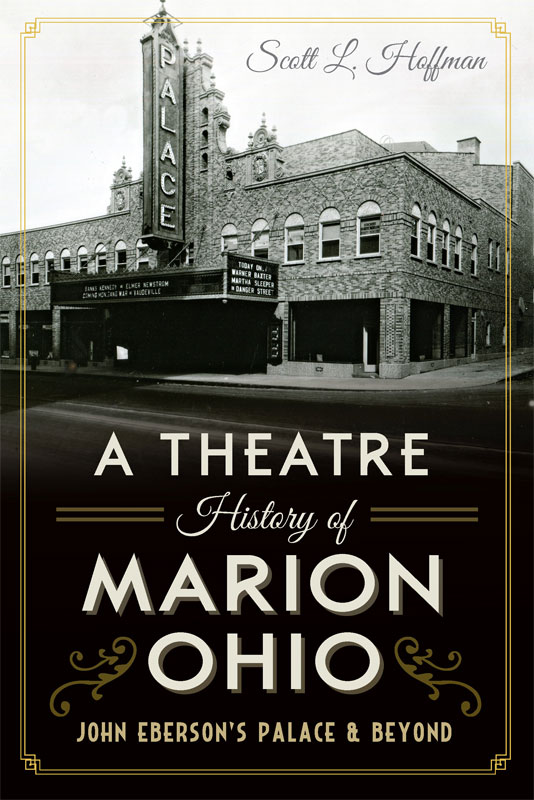

Cover image Lew Lause. Used by permission.

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.481.0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014957209

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.950.7

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Dedicated to all of the members of the Palace Cultural Arts Association, past and present, who with steady persistence overcame difficulties, obstacles and sometimes discouragement to preserve a Marion landmark.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am indebted to several collectors of Marion, Ohio postcards, photographs and artifacts who kindly helped me in preparing this book.

Randy Winland, author of Marion in the Arcadia Publishing Postcard History Series, opened his home and extensive collection to me and provided comments on an early version of the manuscript. He also lightened my workload by guiding research for me at the Marion County Historical Society. I benefited from his extensive knowledge and thoughtful comments about Marion history.

Mike Perry also opened his home and equally extensive collection to me. His personal collection of theatre photographs and programs was particularly helpful to me in researching the other theatres of Marion.

The Marion County Historical Society and the Palace Cultural Arts Association each generously made their archives available to me, and I am grateful for their help. These are excellent organizations and deserve our support. If you are not a member, I encourage you to join.

Finally, I am grateful to Lew Lause, photographer, whose images of the Marion Palace Theatre capture both the beauty of the Marion Palace Theatre and the spirit of John Ebersons creativity.

INTRODUCTION

Motion picture palaces were buildings of escape, fantasy and illusionunique architectural reflections of America in the 1920s. They were gaudy and ornate yet comfortable and approachable. They were aristocratic in name and design yet egalitarian in use. They were opulently decorated yet designed for commercial use. They used modern theatre equipment yet hid it behind a contrived faade of antiquity. Most significantly, they were an expression of the pervasive consumerism that occurred in the 1920s, an ideology that permanently altered the way Americans lived and interacted with the world.

Exhausted by the human losses of World War I and the tragedy of the Spanish flu epidemic, Americans hungered for normalcya term coined by Warren G. Harding. The entertainment business was happy to oblige. While vaudeville had been on a slow decline since the early 1910s, the silent motion picture business was booming. With the advent of the feature-length film, Americans were no longer willing to be entertained while seated on hard wooden chairs in poorly ventilated, family-owned storefront nickelodeons. The motion picture palaces provided the comfort patrons wanted, each with 1,500 to 3,000 seats or more to satisfy growing demand.

That demand seemed almost insatiable. Newspapers fed the appetite with stories about new productions and the gossip about movie stars. Americans bought tickets for pictures featuring swashbuckler, horror and romantic comedy themes. Douglas Fairbanks, Greta Garbo, Mary Pickford, Lillian Gish, Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Clara Bow, Gloria Swanson, Joan Crawford and John Barrymore were as well known then as movie stars of today.

But it was not professional theatre. Some Americans were still conservative enough to raise an eyebrow about motion pictures. They were still associated in the popular mind with dark nickelodeons and risqu vaudeville. Neither satisfied the highbrow definition of legitimate theatre. Motion pictures were simply not serious.

The motion picture palace provided that legitimacy. In one respectable building, architects made space for motion pictures, live orchestra music, organ music, stage productions and family-oriented vaudeville. Patrons of all walks of life could be culturally comfortable in these buildings, without fear of criticism for attending.

The Marion Palace Theatrea motion picture palacefit exactly into this formula. It was designed for theatre productions, motion pictures and vaudeville. The stage could accommodate large productions, and the pit was designed for a small orchestra. The auditorium was spacious, well ventilated and fitted with comfortable leather seats.

Architecturally, it was a marked departure from earlier theatres. Rather than an ornate box, it was designed as an atmospheric theatre, in this case a palace on the exterior and a courtyard on the inside. Reproductions of famous Greek and Roman statues placed in niches and balconies throughout the auditorium created a sense of culture and refinement. A statue of George Washington, guarding the balcony, reassured patrons that the theatre was as legitimate as the country.

An added benefit of the atmospheric style of a motion picture palace was the sense of immersion that it provided. Theatre patrons bought not only a ticket for entertainment but also a ticket to enter another world. Like the motion pictures they watched on the screen, the Marion Palace interior was exotic, romantic and melodramatic. The patrons often described that they felt part of the motion picture, enveloped by both the screen and the interior.

For the thirty thousand residents of Marion, the Palace continued the citys transformation from a dusty manufacturing town to a well-known, modern city with a new hotel, interurban rail transportation and an enviable industrial rail system. Money was plentiful among the nouveau riche industrialists who made Marion their home. Plentiful also were the political contacts citizens made during the presidency of Warren G. Harding, who lived in Marion during his adult life. What it lacked was a modern, permanent home for a cultural life. The Marion Palace provided it, and the entire city gushed with delight on August 30, 1928, its opening night.

The interior of the Marion Palace Theatre today. View from the orchestra section that is under the balcony. Courtesy of Lew Lause. Lew Lause.

Even as the Palace opened, entertainment had changed. Designed for talkies, the Palace had to open with a silent motion picture because the needed equipment for sound motion pictures had not arrived. The success of talkies, a new technology only two years before, had been widely successful. Vaudeville could not compete, and its own stars contributed to the demise of its popularity as they recorded their acts on film, resulting in no demand to see live acts that had already been seen on film.

Before the end of the decade, the Great Depression would shatter the dreams for Marions expansion. Population growth stalled, jobs were lost and fortunes evaporated. By 1933, movie attendance had fallen nationwide by 40 percent. In Marion, it was likely a larger decline. Those who could afford tickets bought them to escape. To counteract the possibility of an even larger decline, the Palace, like other theatres, reduced ticket prices, gave away dishes and offered sweepstakes. It even made an attempt to bring back vaudeville. Those who could not afford tickets needed escape the most. Ketchup soupliterally hot water and ketchupgot some through the day. As desperation increased, so did crime, and the Palace was robbed twice.

Next page