CONFRONTING THE CLASSICS

ALSO BY MARY BEARD

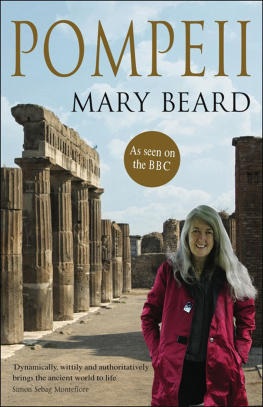

Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town

The Parthenon

All in a Dons Day

Its a Dons Life

The Roman Triumph

CONFRONTING THE CLASSICS

Traditions, Adventures and Innovations

MARY BEARD

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3A Exmouth House

Pine Street

London EC1R 0JH

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright Mary Beard Publications Ltd, 2013

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Clays, Bungay, Suffolk

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78125 048 8

eISBN 978 1 84765 888 3

The paper this book is printed on is certified by the 1996 Forest Stewardship Council A.C. (FSC). It is ancient-forest friendly. The printer holds FSC chain of custody SGS-COC-2061

This book is for Peter Carson

contents

PREFACE

This book is a guided tour of the classical world, from the prehistoric palace at Knossos in Crete to that fictional village in Gaul, where Astrix and his friends are still holding out against the Romans. In between we encounter some of the most famous, or infamous, characters in ancient history: Sappho, Alexander the Great, Hannibal, Julius Caesar, Cleopatra, Caligula, Nero, Boudicca and Tacitus (and thats just a selection). But we also get a glimpse of the lives of the vast majority of ordinary people in Greece and Rome the slaves, the squaddies in the army, the millions of people across the Roman empire living under military occupation (not to mention my own particular favourite, from , Eurysaces the Roman baker). What made these people laugh? Did they clean their teeth? Where did they go if they needed help or advice if their marriage was in trouble, or if they were broke? I hope that Confronting the Classics will introduce, or re-introduce, readers to some of the most compelling chapters of ancient history, and some of its most memorable characters from many walks of life; and I hope it will answer some of those intriguing questions.

But my aim is more ambitious than that. Confronting the Classics means what it says. This book is also about how we can engage with or challenge the classical tradition, and why even in the twenty-first century there is so much in Classics still to argue about; in short, its about why the subject is still work in progress not done and dusted (or, in the words of my sub-title, why its an adventure and an innovation as well as a tradition). I hope that this comes across loud and clear in the sections that follow. There should be some surprises in store, as well as a taste of fierce controversies old and new. Classicists are still struggling to work out what exactly the horribly difficult Greek of Thucydides means (were doing better, but were not there yet), and we are still disagreeing about how important Cleopatra really was in the history of Rome, or whether the Emperor Caligula can be written off as simply bonkers. At the same time, modern eyes always find ways to open up new questions and sometimes to find new answers. My hope is that Confronting the Classics will bring to life, for a much wider audience, some of our current debates from what the Persian sources might add to our understanding of Alexander the Great to how on earth the Romans managed to acquire enough slaves to satisfy their demand.

Debate is the key word. As I shall stress again in the Introduction, studying Classics is to enter a conversation not only with the literature and material remains of antiquity itself, but also with those over the centuries before us who have tried to make sense of the Greeks and Romans, who have quoted them or recreated them. It is partly for this reason because theyre in the conversation too that the scholars and archaeologists of earlier generations, the travellers, artists and antiquarians, get a fair share of attention in this book. And thats why the indomitable Astrix gets a look in as well, because lets be honest very many of us first learned how to think about the conflicts of Roman imperialism through his band of plucky Gauls.

It is fitting that all the chapters of this book are adapted and updated from reviews and essays that have appeared over the last couple of decades in the London Review of Books, the New York Review of Books or the Times Literary Supplement. I shall have more to say about the craft of reviewing in the Afterword. For now let me simply insist that reviews have long been one of the most important places where classical debates take place. I hope that those that follow give a flavour of why Classics is a subject still worth talking about with all the seriousness not to mention the fun and good humour that we can muster.

*************

But Confronting the Classics kicks off with a version of the Robert B. Silvers lecture I was more than a little honoured to give at the New York Public Library in December 2011. The title Do Classics have a Future? hits the nail on the head. It is, if you like, my manifesto.

Introduction

DO CLASSICS HAVE A FUTURE?

The year 2011 was an unusually good one for the late Terence Rattigan: Frank Langella starred on Broadway in his play Man and Boy (a topical tale of the collapse of a financier), its first production in New York since the 1960s; and a movie of The Deep Blue Sea, featuring Rachel Weisz as the wife of a judge who goes off with a pilot, premiered at the end of November in the UK and opened in the US in December. It was the centenary of Rattigans birth (he died in 1977), and it brought the kind of re-evaluation that centenaries often do. For years in the eyes of critics, although not of London West End audiences his elegant stories of the repressed anguish of the privileged classes were no match for the working-class realism of John Osborne and the other angry young dramatists. But we have been learning to look again.

I have been looking again at another Rattigan play, The Browning Version, first performed in 1948. It is the story of Andrew Crocker-Harris, a forty-something schoolteacher at an English public school an old-fashioned disciplinarian who is being forced into early retirement because of a serious heart condition. The Crocks other misfortune (and the Crock is what the children call him) is that he is married to a truly venomous woman called Millie, who divides her time between an on-off affair with the science teacher and devising various bits of domestic sadism to destroy her husband.

But the title of the play takes us back to the classical world. The Crock, as you will already have guessed, teaches Classics (what else could he teach with a name like Crocker-Harris?), and the Browning Version of the title refers to the famous 1877 translation by Robert Browning of Aeschylus play Agamemnon. Written in the 450s BC, the Greek original told of the tragic return from the Trojan War of King Agamemnon, who was murdered on his arrival home by his wife Clytemnestra and by the lover she had taken while Agamemnon had been away.

Next page