A rather underwhelming ruin on the shores of Asia Minor; a prehistoric stronghold associated with conflict and destruction. Why begin with Troy?

It is tempting to answer that question in the melodramatic clich, one man... with the name added in a Hollywood growl: Homer. The temptation is dangerous, not least because we know so little about the existence of this individual. Yet Troy depends upon him; and this city, as he imagined it, is where classical civilization begins.

Around the middle of the eighth century BC over 2,700 years ago it seems that a certain professional poet, known to posterity as Homer, gained a reputation for reciting stories cast in epic verse. This was not rhyming poetry, but it had a strong rhythm or beat; and its subject was strong, too. Epic denotes a narrative set in the age of heroes great-hearted, muscular characters whose deeds make the lives of ordinary mortals appear puny by comparison. Homers name is attached to a pair of epic poems that constitute the founding works of Western literature. One is the Iliad, which describes certain events during a protracted siege of Troy by a contingent of Greek warriors led by Agamemnon; the other is the Odyssey, which tells how one of those Greek warriors, Odysseus, made his adventurous way home after Troy was eventually taken.

Homer did not come from Troy. That sounds like an odd statement, since although his own epics do not directly recount the destruction, he was well aware that Troy had been burned to the ground. But Homer was probably born not far away from the site of Troy on the island of Chios, perhaps, or at the port settlement of Smyrna (modern Izmir). He may have paid a visit to the site: in his day, it was somewhat ruined, but not entirely abandoned. Troy was only one of the various names that existed for the place. Once it had been listed in the territory of the ancient Hittite empire as Wilusa. The Greeks knew it as Ilios, Ilion or Troia; sometimes Homer also calls it Pergamos, which can mean just citadel. Dilapidated as it was, however, Troy stood proud in collective memory. The city, by the agony of its end, was symbolic of all cities; and the strip of land between the city and the sea the Trojan plain, where most of the fighting took place became a precious portion of the earths surface where mortals were transfigured, by violence raw and refined, into demigods.

The coastline has shifted since Homers day. But it is still possible to stand upon the excavated foundations of Troys towers and gaze across to where the Mediterranean narrows as it prepares to join the Black Sea: the passage known as the Hellespont, or the straits of the Dardanelles. The traffic of modern shipping is continuous: one would not dare to swim the intercontinental distance without special arrangements. Little historical imagination is needed to suppose that there was once a time when Troy monitored access through these waters, and therefore that it was a contested location. Trade routes, however, did not concern our poet rather, it was the flux of events long ago. We would describe these events as mythical, perhaps intending myth to mean made up or fictional, and certainly different from history. Such a distinction post-dates Homer. For him, Troy once prospered as a kingdom ruled by the descendants of Dardanus, an offspring of the god Zeus. But already the city was subject to attack (by Herakles, another son of Zeus) during the reign of Laomedon; and though handsomely rebuilt by Laomedons son, Priam, Troy would not survive.

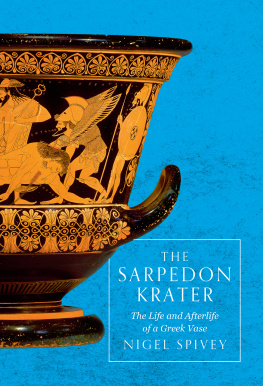

How Troy became a rich and eminent place, and whether its wealth was enough to invite raiders, are questions of no importance for Homer. He is only aware of the poetic cause of the war that brought down Priams Troy. In summary, this can seem whimsical, even ridiculous, but since Homer assumes we know it, the story should be outlined. It begins with an incident at a wedding celebration. The happy couple, Peleus and Thetis, have issued invitations to the Olympian deities the gods and goddesses of the Greek pantheon, whose primary habitat was imagined upon Mount Olympus, on the confines of Thessaly and Macedonia. While these deities are gathered at the marriage feast, a strange dispute breaks out. Three goddesses Hera, Athena and Aphrodite are at a table where a golden apple appears. They do not know it, but this unusual fruit has been slyly placed there by another deity, one whose nature was to cause trouble Ares, god of war. The apple carries an inscribed message: For the Fairest.The three ladies reach for it all at once.

The dispute that duly arises is not one that Zeus, as most senior of the Olympian deities, feels sufficiently impartial to judge (though liberal in his dalliance elsewhere, he is after all married to Hera). So Zeus delegates to a mortal the task of deciding which of the three goddesses is most beautiful. This mortal happens to be a young man called Paris one of many children born to theTrojan king Priam.The divine messenger Hermes brings Hera, Athena and Aphrodite for the resultant Judgement of Paris. Each goddess tries to bribe him. Hera offers the promise of kingly power (Paris, with at least one older brother, was not otherwise in line for royal succession). Athena offers him renown in war (though a good shot with bow and arrow, Paris was not the most redoubtable fighter). For her part, Aphrodite teases Paris with the prospect of love. More precisely, she promises him the favours of the worlds loveliest woman.

Paris nominates Aphrodite for the golden apple. Then the grave consequences of his choice become stark. For the worlds loveliest woman is not, to put it crudely, available. Her name is Helen; she is the wife of Menelaus, king of Sparta. If he wants Helen as his prize, Paris must go to Sparta and steal her.

So he does. And this is how Helens becomes the face that launched a thousand ships for Menelaus was not the sort to endure an outrage to his honour. He called upon not only his powerful brother Agamemnon to assist with vengeance, but many other chieftains. Some, notably Odysseus, contentedly ruling his island of Ithaca, were reluctant to join the expedition to regain Helen from Troy. But their muster of a thousand ships was impressive nonetheless. Led by Agamemnon, they set sail for Troy in the faith that this force comprised the best of the Achaeans.

Achaeans is Homers name for them. The country of Greece did not exist in his time; actually, it did not come into existence as a nation-state until AD 1821. In any case, Homer set his story in the past. Broadly, the Achaeans equate to Greeks of a prehistoric period. Homer describes their physical presence with awe: beyond their frightening readiness for combat, the Achaean heroes are capable of tossing enormous boulders that no individual in Homers time could even budge and they have appetites to match, feasting nightly upon slabs of roast meat. Yet the poet enters their world without any imaginative inhibitions. All that the heroes say is heard, and cast into direct speech: so we learn, verbatim, how Agamemnon as senior commander quarrels with the most fearsome and egotistical of his subordinate warriors Achilles, the offspring of Peleus and Thetis. Homer reports what the Olympians say, too: supernatural though they are, the deities also squabble, take sides, and have grievances to settle.

So it is that while some details of a characters background remain ill-defined was Agamemnon king at Mycenae, or Argos? Homers epic narrative is both fantastic and plausible. Of course he did not himself concoct all elements of the stories; and we must remember that the

Next page