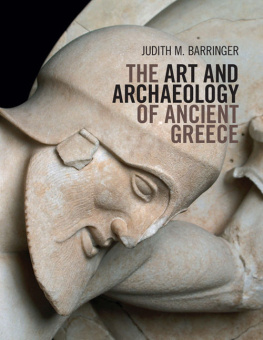

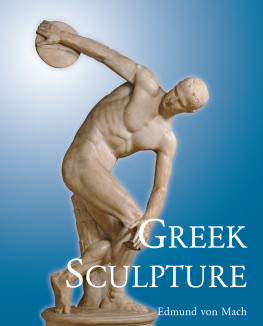

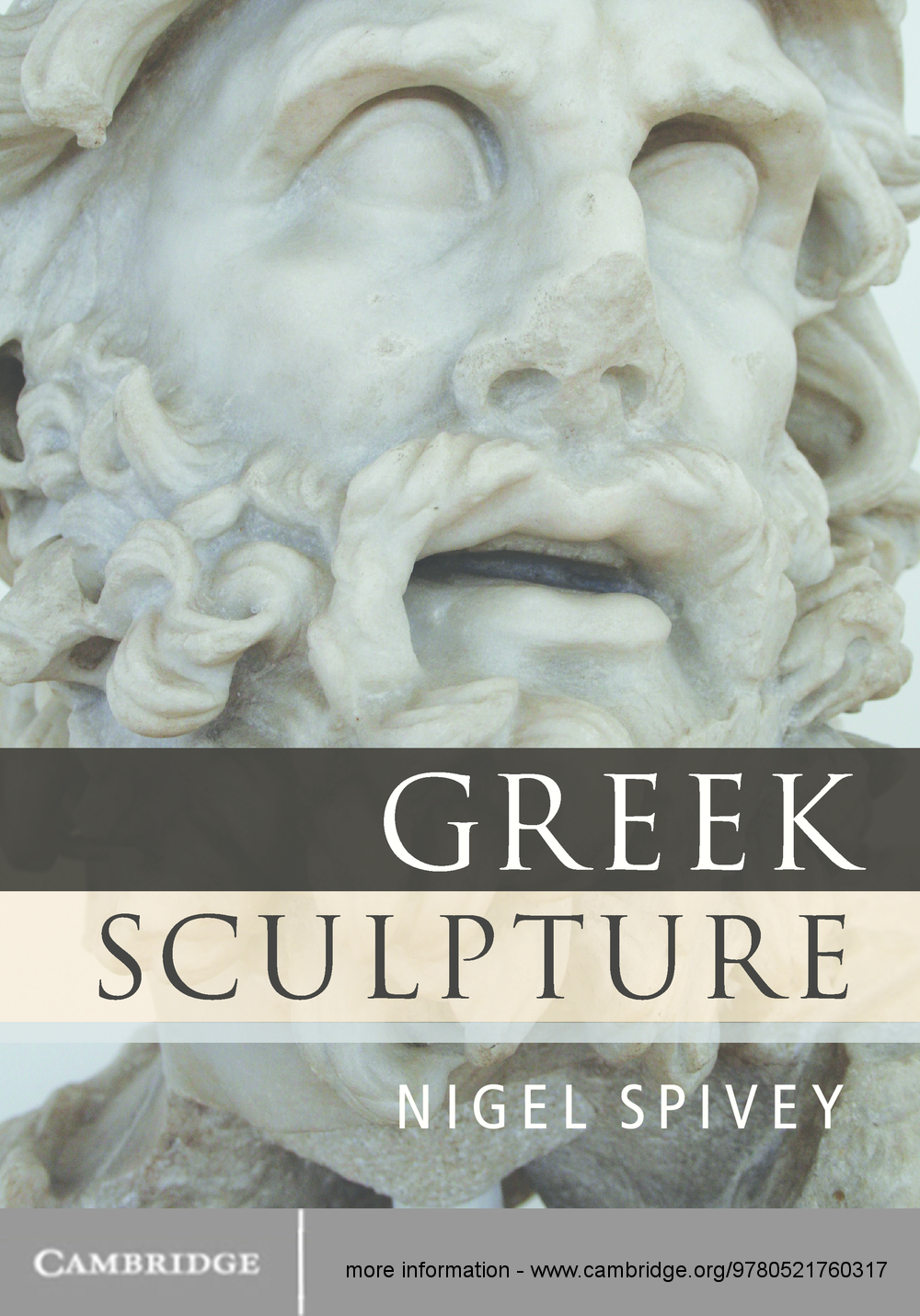

Greek Sculpture

Ancient Greek sculpture seems to have a timeless quality provoking reactions that may range from awe to alienation. Yet it was a particular product of its age, and to know how and why it was once created is to embark upon an understanding of its Classic status. In this richly illustrated and carefully written survey, encompassing works from c. 700 BC to the end of antiquity, Nigel Spivey expounds not only the social function of Greek sculpture, but also its aesthetic and technical achievement. Fresh approaches are reconciled with traditional modes of study as the connoisseurship of this art is sympathetically unravelled, while source material and historical narratives are woven into detailed explanations, putting the art into its proper context. Greek Sculpture is the ideal textbook for students of Classics, Classical civilization, art history and archaeology and an accessible account for all interested readers.

NIGEL SPIVEY teaches Classical Archaeology at the University of Cambridge, where he is also a Fellow of Emmanuel College. He has held scholarships at the British School at Rome and the University of Pisa, and has also worked at the Australian National University and the Getty Research Institute. He has written widely about Greek, Etruscan and Roman art, and presented several historical television documentaries, including the major BBC/PBS series How Art Made the World (2005).

Greek Sculpture

Nigel Spivey

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, So Paulo, Delhi, Mexico City

Cambridge University Press

The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK

Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York

www.cambridge.org

Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521760317

Nigel Spivey 2013

This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press.

First published 2013

Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge

A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data

Spivey, Nigel Jonathan.

Greek sculpture / Nigel Spivey.

pages cm.

ISBN 978-0-521-76031-7 (Hardback) ISBN 978-0-521-75698-3 (Paperback)

Sculpture, Greek. I. Title.

NB90.S65 2013

733.3dc23

2012021706

ISBN 978-0-521-76031-7 Hardback

ISBN 978-0-521-75698-3 Paperback

Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Je voudrais que le lecteur ne crt rien sur parole et sans l'avoir vrifi, et qu'il se mfit de tout, mme de cet itinraire. Croire sur parole est souvent commode en politique ou en morale, mais dans les arts c'est le grand chemin de l'ennui.

STENDHAL, Promenades dans Rome, 25 Janvier 1828

Figures

My thanks to colleagues who have assisted with pictures: Lucilla Burn, David Gill, Ian Jenkins, Bert Smith, Cornelia Weber-Lehmann. I am also obliged to John Donaldson at the Museum of Classical Archaeology, Cambridge. Museum references (especially those of Berlin, currently under reorganization) are provisional: here, the following abbreviations have been used: BM British Museum; NM Athens, National Archaeological Museum.

Frontispiece: Laocoon a sketch attributed to Michelangelo, in the underground room of the New Sacristy of San Lorenzo, Florence.

Colour Plates

I

Portrait of J.J. Winckelmann, by Anton von Maron, 1768. Weimar, Schlossmuseum.

II

(a) Detail of Riace Figure B. Reggio Calabria, Archaeological Museum (Nick Murphy).

(b) Detail of Riace Figure A. Reggio Calabria, Archaeological Museum (Nick Murphy).

III

Detail of painted drapery on Athens Akropolis kor no. 594, as recorded at time of excavation. After H. Schrader, Auswahl archaischer Marmor-Skulpturen im Akropolis-Museum (Vienna 1913), pl. V.

IV

Part of a fragmentary Attic funerary stl , c . 540 BC: girl with flower. Berlin, Staatliche Museen. (Further parts of the same monument are in the New York Metropolitan Museum.)

V

Reconstruction of the Triton pediment: after T. Wiegand, Die archaische Poros-Architektur der Akropolis zu Athen (Cassell 1904), pl. iv. (Original fragments in Athens, Akropolis Museum.)

VI

Reconstruction of the chryselephantine Zeus at Olympia. Artwork by Sian Frances.

VII

Detail of the Terme Boxer. Rome, Palazzo Massimo.

VIII

Figure N usually identified as Iris from the Parthenon west pediment. London, BM.

Figures in text

Preface

This book is the offspring of another. Entitled Understanding Greek Sculpture , it was published in 1996 and went out of print several years ago. As any author would, I wished for a reissue or rather, a second edition, correcting and updating where necessary. This wish developed into the more ambitious project of entire renovation. Motives were mixed: since I could not trace the floppy disk where the words of the original text were stored, the book would have to be rewritten but in any case I was glad of the opportunity to implement numerous pentimenti of style and substance, while adding several further chapters and extra material throughout.

The basic structure remains along with the intention to provide an understanding of Greek sculpture. In a fresh introductory section I have outlined the historic and aesthetic justification for studying this body of ancient art; here it may be worth adding a reminder that the power of art is rarely self-sufficient. If artists of today require (as they seem to) critics and commentators to explain their work, how much greater the need for glossaries on work produced 2,000 or more years ago? And naturally we create our own academic priorities for this as for any other field of study. Since 1996, there have been two distinct trends in research and writing about Classical art in general, and Greek sculpture in particular. The first has been to investigate the viewer's share to focus not so much on how images were produced as on how they were received. It remains rare to have any insight about the contemporary response to sculptures of the fifth century BC and earlier. Yet the exploration of later texts related to images and attention to the literary genre of ekphrasis the descriptive speaking-out of writers alluding to works of art, from Homer onwards has become more sensitive and sophisticated; and there is even some fresh evidence (notably from papyrus remains of the third-century BC poet Posidippus). An evolutionary and collective account of ancient response is still difficult to compose. This study, nonetheless, tries to maintain alertness to the religious power of images in their original function: a theology of viewing wherever sculpture was once situated.