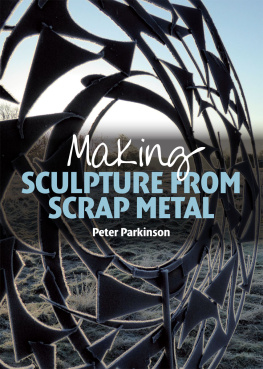

Peter Parkinson

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2015 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

Peter Parkinson 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 022 5

Frontispiece

Eumenides II Medusa, a sculpture with four faces, by Ian Campbell-Smith. Made from steel artefacts found on the shores of the Thames and Medway. Part of a series deriving from Graeco-Roman mythology.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

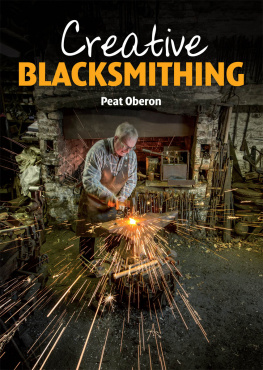

Window II by Hamish Black. An echo of the distorted perspective of cubist, still-life paintings by Picasso, Matisse and Czanne.

At least four thousand years ago Bronze Age metalworkers in Britain were hoarding broken axes, swords and other scraps in order to re-use the metal, just as Iron Age smiths did later. Metal was too precious to throw away. Following the capture of Constantinople by the Crusaders in 1204, ancient bronze statues were melted down to provide the metal for new works. During the Napoleonic wars, bronze statues were melted to make cannon. Two world wars swallowed and re-generated huge amounts of metal, from huge amounts of scrap. There is nothing new about metal recycling.

Bronze sculpture is traditionally produced by a specialist foundry, making a mould from the master pattern produced by the sculptor, sometimes enlarging the sculptors maquette to make a larger work. The practical skills of the sculptor were in modelling or carving rather than in working metal.

The use of scrap metal to make sculpture is a twentieth-century development. The beginnings can be seen in a move towards directly constructed metal sculpture, where the sculptor assembles the components. In 1912, as a kind of three-dimensional cubist collage, Pablo Picasso produced a sheet metal and wire sculpture entitled Guitar.

In 1913, the Dada artist Marcel Duchamp made his Cycle Wheel, which was indeed a bicycle wheel and forks, mounted upside down on the seat of a tall wooden stool. A year later his Bottle Rack became the second of what he called ready-mades: not an assemblage, but an existing metal object, bought from a shop and presented ironically, as art. Both sculptures in a sense used scrap metal, in the form of found objects.

Following the armament demands of World War I, the technology of gas and arc welding became widely available. For sculptors traditionally trained in carving wood or stone, or modelling in clay or plaster, the opportunity to work metal directly offered a new approach to the making of sculpture. The properties of iron and steel allowed constructions to be massive or fine, monolithic or linear, strong or apparently fragile, offering new qualities and a new freedom, which Julio Gonzalez described as the ability to draw in space. During the 1930s Gonzalez created a large number of metal sculptures, and with his welding and blacksmithing skills, helped his friend Picasso produce a series of sculptures, including Head of a Woman, made from sheet metal and lengths of scrap coil spring, used to represent hair.

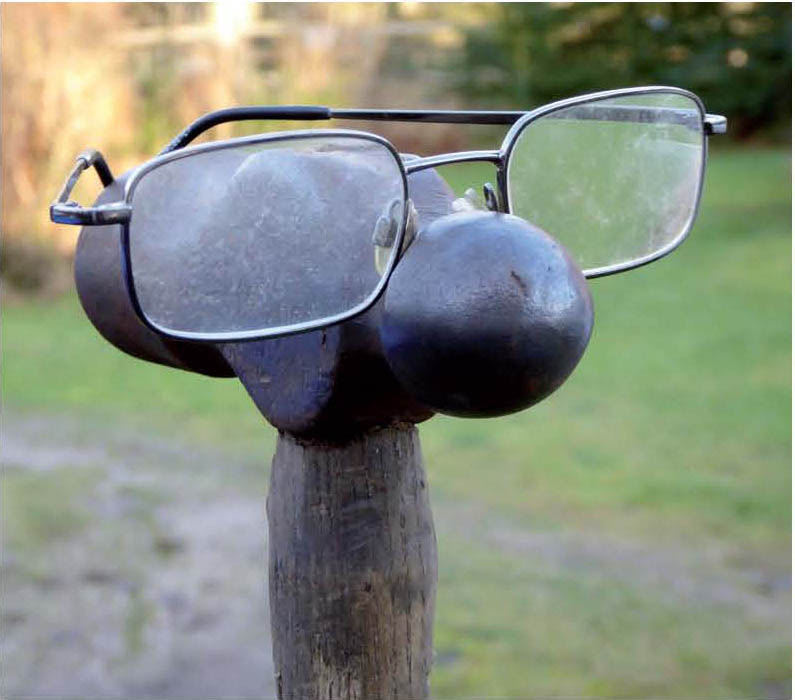

While Picasso was far from a lone pioneer, his work records the development of direct metal sculpture. With hindsight perhaps, his Head of a Bull, created in 1943, provides the seminal statement about sculpture from scrap, consisting simply of a bicycle saddle the head supporting a pair of handlebars the bulls horns. With just two components, this is the kind of visual pun that exemplifies some of the appeal of sculpture made from scrap metal. Head of a Bull is recognizably a bulls head with horns, yet it is equally identifiable as two bicycle components, a visual ambiguity which can be amusing, captivating and witty.

From such beginnings, making sculpture from scrap metal became an accepted artistic medium, as exemplified by David Smith in America, Anthony Caro in England and others in Europe and Russia.

I am greatly indebted to a number of sculptors who work with scrap metal today, and have generously provided many of the illustrations in this book. These have been chosen to demonstrate a range of approaches, and the distinctive character of the work of each sculptor.

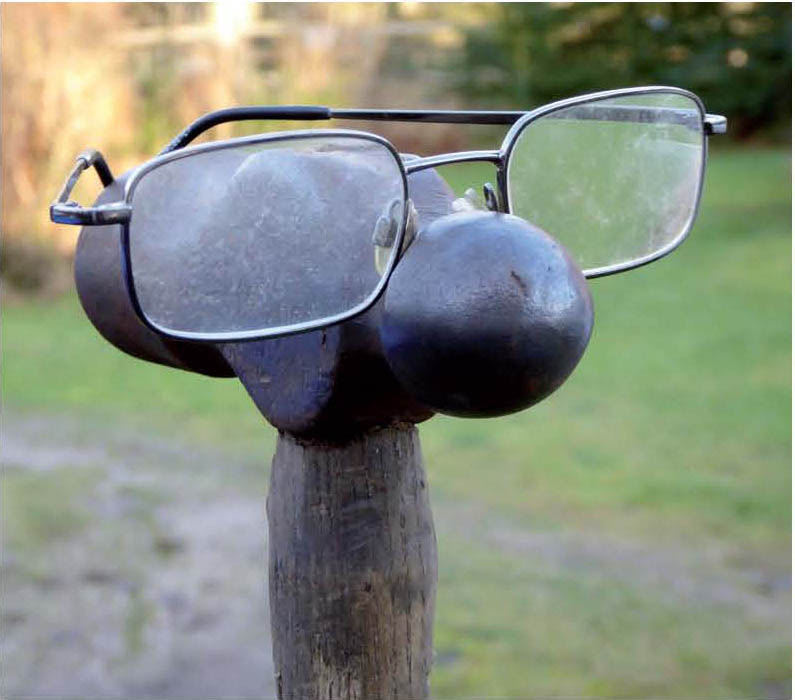

Hammer Head. Clearly not Picassos Head of a Bull, made from a bicycle saddle and handlebars, but a similar conjunction to make the important point that we can read significant visual references into very little.

Why Use Scrap?

Making sculpture from scrap metal begs the fundamental question why use scrap when clean new metals are readily available?

- Making sculpture in this way offers the sculptor a directness and immediacy, and by definition gives rise to unique pieces of sculpture. No two sculptures can be the same

- Using scrap metal is about transformation, providing a visual challenge in identifying and selecting components and turning the abandoned detritus of civilization into something with meaning and value

- Artists are usually wary of the word inspiration, which seems to suggest the sudden illumination of that cartoon, mental light bulb. Ideas can come fully formed, but they are more often the result of plain hard work. Scrap metal components are not simply a kit of parts, but in their extraordinary variety can themselves provide a rich source of ideas

- Using scrap metal components makes possible a kind of visual pun, the added dimension of interpretation and association. The old pliers used as the ears of a hare are understood both as ears, and as tools, introducing the viewer to an intriguing ambiguity

- In some cases the source and nature of the components may add another quality and significance. The sculpture of a farm animal may utilize recognizable agricultural scrap, the sculpture may incorporate metal components of significance to those who commissioned it, or they may have been found near the location of a site-specific sculpture

- Creating sculpture from scrap metal can be a powerful philosophical gesture, giving new life to the things we throw away. Just as the sculpture itself represents an idea, the way it is made can also carry a message

- At a purely practical level, using scrap metal provides an opportunity for making sometimes sizeable pieces of metal sculpture for a relatively low cost, in materials that are tough and durable

- And finally, like opening presents at Christmas or looking for pebbles on a beach, behind a serious business there is an almost childish pleasure in visiting a scrapyard and seeking out interesting pieces

Next page