Published in 2017 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2017 by Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2017 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

To see additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, go to rosenpublishing.com.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering: Executive Director, Core Editorial

Anthony L. Green: Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Rosen Publishing

Kathy Campbell: Senior Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Michael Moy: Designer

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Carina Finn: Photo Researcher

Supplementary material by Cleo Kuhtz

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kuhtz, Cleo, editor.

Title: Sculpture : materials, techniques, styles, and practice / Edited by Cleo Kuhtz.

Description: First Edition. | New York : Britannica Educational Publishing in Association with Rosen Educational Services, 2017. | Series: Britannicas Practical Guide to the Arts | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015048113 | ISBN 9781680483659 (eBook)

Subjects: LCSH: Sculpture--Technique--Juvenile literature. | Artists materials--Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC NB1143 .S38 2016 | DDC 730.28--dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015048113

Photo credits: Cover (inset images, from left) Diego Cervo/Shutterstock.com, Dean Drobot/Shutterstock.com, itonggg/Shutterstock.com; cover (background), Studio 9/Shutterstock.com; back cover and interior pages stripe pattern Eky Studio/Shutterstock.com; additional cover and interior page border patterns and textures Dragana Jokmanovic//Shutterstock.com, somchaiP//Shutterstock.com, Alina G//Shutterstock.com, Pattanawit Chan//Shutterstock.com

CONTENTS

A rt is a means of organizing experience into ordered form. The experience thus translated into a sculpture, song, painting, or poem can then come to life again in the consciousness of other people. It may truly be said that only when this sharing takes place has a work of art been fully realized. That is why art is properly regarded as a language.

To understand the artists language, however, requires a little effort. Looking at a work of art, like listening to music, becomes a rewarding experience only if the senses are alert to the qualities of the work and to the artists purpose that brought them into being. The language of sculpture, then, must be learned.

Sculpture, like other arts, is a record of human experience. From earliest times to our own day, sculpture records experiences that range from wars and worship to the simplest joys of seeing and touching suspended shapes designed to move in the wind. In sculpture there is everything from the marble gods of Phidias to the mobiles by Alexander Calder. People everywhere have found the need for sculpture, whether it be in work, in play, or in prayer. Sculpture also records the desire to commemorate the deeds of nations and of individuals.

The Burghers of Calais, a sculpture by Auguste Rodin, is a monument to a historic moment of French dignity and courage. The moment expressed through the six figures is one of trial and triumph. The year depicted in the masterpiece was 1347; the place, outside the gates of Calais, was a heavily invaded port town. The English, led by their king, Edward III, had laid siege to the town and starved it into submission. The terms for surrender required that six men come with halters about their necks to deliver the keys of the town.

Auguste Rodin depicted a poignant moment during the Hundred Years War in The Burghers of Calais (1889). The tragic yet heroic six figures, executed in bronze, now are located near the Calais town hall.

The fate of these men was clear. They were to pay the penalty for resistance, but in delivering themselves as hostages they would assure safety for the rest of the town.

It was to the memory of the man who volunteered first, Eustache de St-Pierre, the richest burgher of the town, that in 1884 the grateful people of Calais ordered a statue. In working out the idea, however, Rodin was so moved by the incident that he decided to add the five men who volunteered to accompany the leader. Four years after beginning this work, Rodin had given form to his idea and had finally cast it in bronze.

Rodin gives St-Pierre determination and poise. He holds the key to the city, and around his neck is the rope, or halter, prescribed by the conquerors. A companion, with his head buried in his hands, is on the right. These two men exemplify the greatest contrast of feeling in the group. By placing them together Rodin achieves dramatic power. To organize, or compose, six different figures into a single unified work of art, Rodin groups them into three pairs, each pair differing from the other and yet tied to the others in rhythmic movement. The spaces between the figures are also varied. This is what sculpture tries to achieve, for sculpture deals essentially with the purposeful relationships of volumes in space.

By looking at the details of the sculpture one can see Rodins ability to convey feeling through facial expression and through hands. He cuts the hollows of the face deeply to assure strong shadows, and his textured surfaces catch the subtle variations of light and heighten the sense of life and movement. This irregular surface is a departure from the cold, impersonal smoothness of the classical tradition. Together with a profound sense of power and drama, it had a tremendous influence on the sculptors of Rodins time and helped to determine the trend of modern sculpture.

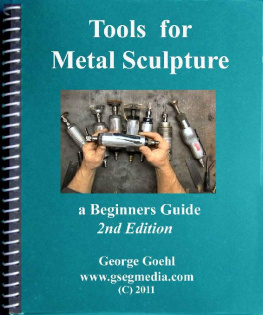

While working on a statue, the sculptor relies on proper light to study the planes by which masses turn from the light into the shade, creating the sense of solidity and third dimension. Only by light properly cast can the sculptor study shape, texture, and character.

The sculptor strives to show the finished work in the same light by which it was originally sculpted. A light cast too weakly or too strongly from a source too high or too low can completely change the appearance of the work. It can undo the effort of the sculptor and destroy the effectiveness of the creation.

Paintings too depend on light but not in the same sense as sculpture. The painter asks only that the whole surface of the picture receive uniform and sufficient light for proper viewing. The light and shade used on a face or figure to give it roundness and solidity cannot be altered by an external light. In sculpture, on the other hand, volume and character are brought to life only through light and can be altered at will by the control of light. Proper lighting at night of a statue outdoors also requires skill.

Sculpture differs from painting in another significant respect. A painting, being flat, can show only the view taken by the painter. A statue in full round can be seen from a variety of angles. Consequently the sculptor strives to achieve sense and rhythm for every possible point of view. Sculpture is thus endowed with a variety of interest impossible in painting.