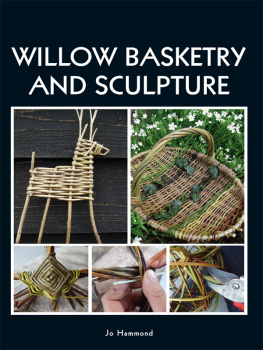

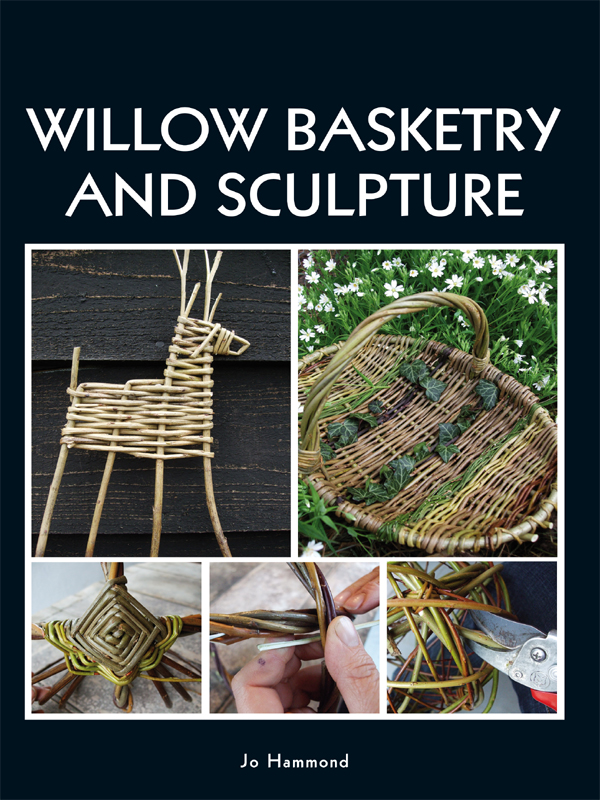

WILLOW BASKETRY AND SCULPTURE

Jo Hammond

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2014 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2014

Jo Hammond 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 682 6

DEDICATION

For my parents, who said I could do anything I set my mind to.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank my husband Martin for buying me the book that started it all off, and for his dedicated hard work building the workshop. Special thanks to Bunty Ball for support, advice, and letting me loose on her basketry collection, and to the Norfolk Basket Company, Peter Dibble and Robert Goodwin for their beautiful photos. Thank you to all the lovely customers and suppliers I have dealt with, and warm appreciation for anyone who has been to one of my classes - you have taught me more than you can imagine. Thanks also to Suffolk Craft Society, for encouragement and inspiration.

CONTENTS

A willow planter in the garden.

INTRODUCTION

My aim in writing this book is to inspire and enable a reader, who has no previous experience, to make a willow basket. In the same way as I was inspired by a book, I want you to see that you can pick up the simplest of tools, buy a bundle of twigs and make something you can be proud of.

More than twenty years ago, in an enviable but penniless situation, I was recently out of college, and living with my partner in a tied cottage in the middle of a wood. Knowing my interest in crafts, he gave me a basketry book. It laid out some varied and interesting projects for the beginner to try, and a couple of them were called 'hedgerow baskets'. These were to be made from wild twigs and climbers, garden plants or leaves, and the photos really did make them look charming. Suddenly the familiar plants around me had a new potential, and their abundance meant that I could have a go at basketry without having to spend any money.

Many foraging trips, many curses later, I had made a basket. It wasn't great, but it was a beginning I suppose it wasn't bad enough to make me want to give up altogether. And having cut my teeth with rough and ready hedgerow materials, when I eventually bought some farmed basketry willow (which was smooth, regular and super-flexible) it seemed easy.

Fast-forward through several years, and I now have a modest career in basketry art, craft and teaching, still inspired by books and the work of gifted makers, still loving the challenge of hedgerow basketry, and now attempting a book of my own. Having taught basic basketmaking skills to many beginners, young and old, I feel I have the experience and knowledge to get people started.

History

Basketry is thought to be one of the oldest crafts in existence, pre-dating pottery. We can imagine how our hunter-gatherer ancestors must have twisted twigs and leaves together to make rudimentary containers for holding the nuts, roots, berries and greenery they harvested from the wild. At some point it was discovered that a regular weave rather than a random one made for a more durable vessel, and the craft had begun.

It is not possible to trace the development of basketry in the same way as, say, metal-working, because thin organic materials just rot and disappear into the soil. Sometimes particular ground conditions do allow larger early artefacts to survive - remnants of woven fish traps from Mesolithic times can appear at low tide in muddy estuaries; remains of wattlework houses have been preserved by peat bogs in Northern Ireland.

Ancient civilizations clearly made and used a wide range of baskets; Roman paintings, sculptures and mosaics depict many elegant basket designs and products including chairs (Pliny mentions reclining chairs) - apparently just like wicker furniture of today.

Much early basketry would have been put together at home for the weaver's own needs in garden, field or kitchen, but as trade increased, the craft became more specialized. Documents show that in Britain, by late medieval times, basketmaking had become a profession with its own trade guild, the workers having as important a place in society as other accomplished craftsmen of the time.

Paintings and documents from the past clearly show how important basketry was to society, but to see really old genuine examples it is worth visiting a museum, particularly a local museum which may have examples of unusual designs particular to a trade or local folklore tradition. In my region of East Anglia there are excellent museums with enlightening displays of highly specialized baskets, associated with fishing and the fishery trade, agriculture and fenland life.

Some evocative, centuries-old basketry fragments can be seen in the Museum of London, saved from decay by either exceptionally dry or exceptionally wet conditions. Willow basketwares were among the astonishingly well-preserved artefacts brought up with the sunken Tudor warship the Mary Rose. A number of woven fragments have been preserved and documented, which although squashed, show familiar techniques and structures. These remains are important not just for what they can tell us about the past, but also to give us guidance as craftspeople trying to preserve skills for the future.

Baskets made from Canadian cedar bark by Bunty Ball.

Twined newspaper basket (unknown maker), and basket made from crisp packets by Amy Chestnutt.

Material and environment

As this is a short book, with limited scope, we are confined mostly to one material basketry willow and to European techniques. However, there is a whole world of variety out there.

Every culture has its own basketry styles, techniques and materials. Local plants are put to use in a range of plaited, twined, interlaced and coiled structures. Resulting products are not just baskets but fences, harness, floorcoverings, toys, shoes and clothing and even houses.

These days there is a new source of material to supply the inventive maker rubbish. As we become more aware of the problems waste can cause, better uses are being found for durable materials that otherwise would be thrown away. Wonderful new baskets combine age-old techniques with materials such as newspaper, old telephone wire, packing tape, cardboard boxes, crisp packets, bottle tops and tin cans. Re-used materials can be woven on their own, or combined with traditional plant materials to aptly express the meeting of the old with the new.

As concern has grown about human effects on the environment, we may look harder at the things we buy and use to see if they can make a more positive or at least less damaging impact. Basketry willow, because it is a renewable wood product, takes carbon out of the atmosphere, locking it up for the life of the article. If you make or buy willow basketwares, keep them, use them, repair them for as long as possible. The best place to put them at the end of their lives is the compost heap, or under a hedge where they can slowly rot down and return to the soil they certainly should not go to landfill. The same is true for any trimmings.