Baleen Basketry

OF THE NORTH ALASKAN ESKIMO

Baleen Basketry

OF THE NORTH ALASKAN ESKIMO

Molly Lee

Foreword by Aldona Jonaitis

New Preface and Introduction by the Author

University of Washington Press

SEATTLE & LONDON

published in association with the

University of Alaska Museum

FAIRBANKS

For my son, his father, and his grandparents

Copyright 1983 by the North Slope Borough

Planning Department, Barrow, Alaska

Foreword, Preface, and Introduction to the 1998 edition

1998 by the University of Washington Press

Printed in the United States of America

All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lee, Molly

Baleen basketry of the North Alaskan Eskimo / Molly Lee

p. cm.

Originally published: Barrow, Alaska:

North Slope Borough, Planning Dept., c. 1983.

With new pref. and introd.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-295-97685-3 (alk. paper)

1. Eskimo basketsAlaska. 2. Whalebone basketsAlaska.

1. Title

E99.E7L417 1998 97-35482

745.593DC21 CIP

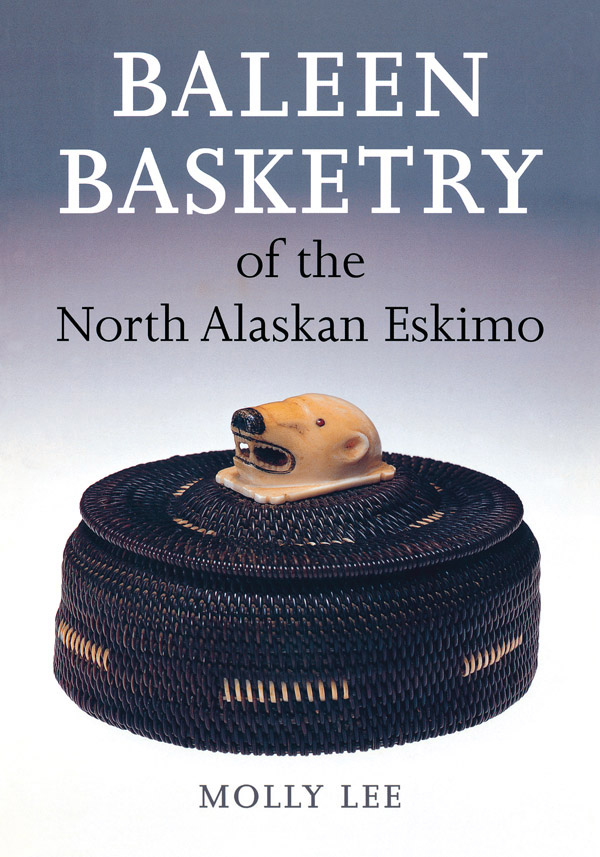

Unless otherwise stated, the baleen baskets illustrated in this book, if decorated, use light baleen and have ivory starter pieces and finials. Measurements are given in centimeters; height precedes diameter. For baskets in public institutions, museum catalogue numbers are given in brackets after the collection identification.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

Contents

by Aldona Jonaitis

Foreword

I met Molly Lee in 1985 at a Native American Art Studies conference where she gave a talk on baleen baskets, a type of art about which I knew virtually nothing. There was a reason for my ignorance: this basketry was not part of a centuries-old indigenous art form and there was little in print about it. Baleen baskets had been invented in the relatively recent past and were made for tourists. Because they could not easily be assigned to categories of mainstream western art, they were generally dismissed as craftwork and thus inferior to the fine arts.

A scholar who was unwilling to adhere to such a restrictive paradigm, Molly Lee treated Inupiat baleen baskets as objects of significant artistic merit, which also embody profound statements of cultural identity. Her trenchant observations at that conference more than a decade ago prompted me, and Im sure others, to rethink objects made for the tourist market as worthy of serious study. Argillite carvings, Eastern Woodlands moose hair embroidery, and Plains ledger drawings, as well as baleen baskets, are just a few examples of art that until recently was disparagingly labeled as acculturated. In the last decades of the twentieth century a new respect for tourist art acknowledges its intrinsic merit, its cultural significance, and its place in the worlds history of art.

It is most fortunate that this book is available again after a decade out of print. It stands as a major contribution to the literature on the enduring vitality of Native art.

ALDONA JONAITIS

Director

University of Alaska Museum, Fairbanks

Preface

T he seed of this study was sown on the June day in 1976 when I first saw a baleen basket. Browsing through the display cases at The Legacy Ltd. in Seattle, a mecca for lovers of Native art, my eye lit on a small black basket with an ivory carving of a seal on its top. The seal was posed as though sunning itself on the spring ice; tiny baleen plugs gave its eyes the right luster, and every whisker on its small snout was exquisitely articulated. Enchanted by the baskets tightly woven, elliptical body, I turned it over and saw that a signature had been etched into the ivory starter disk on its bottom: Abe P. Simmonds, Barrow, Alaska, 1952. It was a name I would come to know well over the next few years. Despite the baskets high price I bought it on the spot. As I walked out of the shop with it, I little realized that I had embarked on a six-year journey that would take me from Barrow, Alaska, to Nantucket, Massachusetts, and through the dusty shelves of libraries, archives, museums, and private collections in between.

This research was undertaken as part of a graduate program in art history at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Frustrated by repeated attempts to find more information on baleen baskets than was available in one brief article (Burkher and Burkher 1954), I decided to research and write about them for my masters thesis. At first the idea met with little enthusiasm from my committee. Baleen basketry was a tourist art, and only a year after the publication of Graburns groundbreaking study Ethnic and Tourist Arts (1976), tourist arts had not been accepted as a legitimate focus of scholarly research. Eventually, however, letters of support from several museum curators in Alaska won over the skeptics, whose enthusiasm thereafter was critical to the completion of the study.

My objectives for the thesis were threefold: to reconstruct a history of baleen basketry, to record its techniques, and to develop a taxonomy for the baskets. As literature on this topic was virtually nonexistent, I had to start from scratch. I interviewed basketmakers and other knowledgeable informants, gathered data from the baskets themselves, and searched archival and library holdings.

I began my research in the summer of 1980 with a months fieldwork in the arctic communities of Point Hope and Barrow, Alaska. How well I remember sitting in an empty teachers apartment in Point Hope, staring out at the Chukchi Sea, trying to summon the courage to knock on the first door. As is so often the case in rural Alaska, the children took care of that. Before I knew it I was being pulled by an army of small hands down the street to the house of Seymour Tuzroyluk, the Episcopal minister and master ivory carver. That month of fieldwork and several subsequent trips to the Arctic formed the basis of my description of technique and were an invaluable means of gaining information about the history of baleen basketmaking in these and surrounding villages.

Creating a baleen basket taxonomy, which depended upon finding a statistically viable corpus of baskets to measure, proved more difficult. I had assumed that I could obtain such a sample (a minimum of a hundred baskets) by canvassing approximately twenty museums in the United States with extensive arctic collections. Few baskets turned up from these sources, however, probably because of their non-legitimate standing. Most baleen baskets at that time were in the hands of private collectors, many of them retired Alaska teachers. Thus, my samplemore than two hundred baskets in allhad to be obtained in twos and threes instead of the tens and twenties I had hoped for.

In the spring of 1981 I made several trips around the United States, visiting old sourdoughs and measuring and photographing their baskets. A more hospitableand patientgroup of collaborators is difficult to imagine. I made many friends, and the memories of those times are with me still. Less entertaining but equally important for patching together the baskets histories was week upon week of archival research, mainly in Juneau, Seattle, and Washington, D.C. Even so, many questions still remain to be answered.