Table of Contents

Praise for Game of Kings:

Lively, inspiring....With [Michael Weinrebs] vivid portraits and brisk narrative style, he manages to find high drama in a roomful of brilliant young minds pushing little pieces across a 64-square grid.

Entertainment Weekly

[Game of Kings] is supported by well-chosen detail, intelligence, and terrific writing. Weinreb clearly develops an affection for the eclectic members of his team, and because of the skill he brings to his project, so will his readers.

Publishers Weekly (starred review)

Compelling....Weinreb paces the action expertly....The seasons ebbs and flows intermingle with the prosaic details of inner-city adolescence to singularly lyrical effect. Kirkus

Entertaining. Newsday

Not only among the very best accounts written about chess, but also among the best nonfiction works 2007 has offered.

OK Gazette

Writing with the deft, propulsive style of a young Frank Deford, Michael Weinreb has captured both the intellectual insanityand the curious normalcyof what its like to be a teenaged super-genius. Game of Kings is the Friday Night Lights of high school chess.Chuck Klosterman, author of Sex, Drugs, and

Cocoa Puffs and Chuck Klosterman IV

Game of Kings is about chess in the same way that Darcy Freys The Last Shot was about basketball. Michael Weinrebs real subjects are the nature of talent, the onset of adolescence, and the kingdom of Brooklyn. This is a wonderful book.

Mark Kriegel, author of Pistol:The Life of Pete Maravich and Namath: A Biography

Michael Weinreb has done a heroic job doing something once thought impossiblemaking an eminently readable topic out of chess. Part Word Freak, part Season on the Brink, Game of Kings is a gripping inside look at an endearingly quirky subculture.

L. Jon Wertheim, author of Transition Game and Venus Envy

Game of Kings isnt so much a book about high school chess as it is an unforgettable journey into the blessing and curse of adolescent genius. With a narrative rich in voicea gathering of intoxicating charactersWeinreb has delivered nothing short of a generational classic. This is a stunning book. You wont soon forget it.

Adrian Wojnarowski, author of The Miracle of St. Anthony

Michael Weinrebs work has appeared in The New York Times, the Boston Globe, the Los Angeles Times, Newsday, and ESPN The Magazine. In his career as a journalist, he has been named best sportswriter in Ohio by the Associated Press, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, and has been cited three times in the Best American Sports Writing anthology. He lives in New York City.

In memory of my uncle,

Mark Rosenbloom (1945-2005),

the first chess player I knew

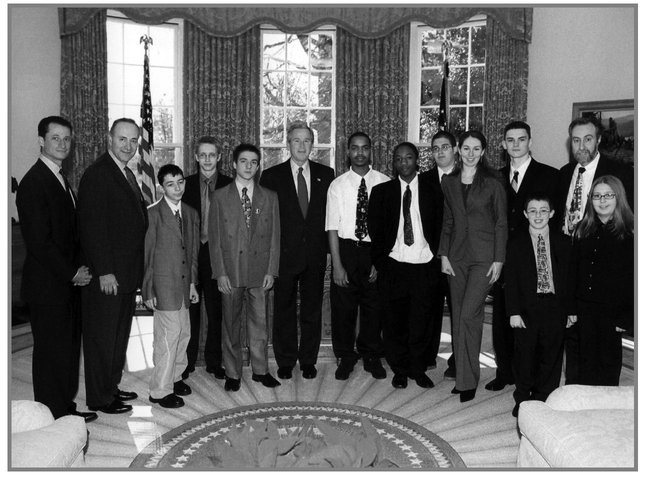

The Murrow team with President Bush (from left to right): Congressman Anthony Weiner, Senator Charles Schumer, Alex Lenderman, Sal Bercys, Ilya Kotlyanskiy, President George W. Bush,Willy Edgard, Nile Smith, Oscar Santana, Olga Novikova, Dmitriy Minevich, and Eliot Weiss with his two children

PROLOGUE

FOUR DAYS AFTER CHRISTMAS, 2004, IN A PIN-DROP-SILENT HOTEL conference room with a panoramic view of a TGI Fridays and an adult bookstore, Oscar Santana nudges a black pawn forward, sweeps a white rook off the board, and presses the button atop his game clock with a faint click.

This is not chess, mutters the man on the opposite side of the board. His name is Norman, according to the pairings board at the Empire City Open, and Norman is regarding Oscar with a slack jaw and a pair of bugged-out eyes. Norman is also wearing a black winter cap indoors, as if to conceal from the outside world the strings that command his elastic facial features. This is not chess, Norman says again, and he is speaking far too loudly now, his voice piercing the white noise of ticking game clocks and humming air vents and muffled coughs.

Norman is approximately three times Oscars age, and a good half a foot taller, and his choice of headwear, coupled with his tics and twitches and grimaces and the plaintive noises he emits through his bulbous lips, lends him the appearance of a burglar trying to make an escape through a narrow air shaft. In truth, the board is shrinking on Norman; there are few safe places for his king to escape. His is, as they say in the sport, a lost game, and there is no worse feeling in chess than the realization that defeat is imminent and unavoidable.

Norman shakes his head and says something utterly incomprehensible. Oscar just sits there, stone-faced, a pair of silver headphones clapped over his ears, a tinny hip-hop beat creeping out from underneath. Then he moves his rook to Normans back row, to threaten his queen. The queen is the most potent piece on a chessboard, the only one capable of moving any number of spaces in any direction, horizontal, vertical or diagonal, and if the queen is crippled, if the queen is retreating instead of attacking... and especially when Norman is already down a rook, because only a pair of rooks can begin to approach the queen in terms of strength... and who the hell is this kid, anyway? Norman has no idea. All he knows is that things have gone wrong, that a seventeen-year-old in baggy jeans and FUBU sneakers has surrounded his king and endangered his queen and taken one of his rooks and rendered him into a stammering caricature.

But its not just Oscars age, and its not merely the fact that his official United States Chess Federation rating, which determines the social order in chess, is nearly three hundred points lower than Normans. More than all of that, its the way this little brace-faced miscreant is beating him, using a bush-league tactic involving a knight and a pawn that even Oscar himself knows is a joke. Its the type of attack that makes very little sense to those with a thorough knowledge of the chessboard. It defies all the conventional wisdom Oscar has picked up over the years: that you should make a concerted effort to control the center of the board in the opening moves of the game, that you should avoid unnecessary sacrifices of your own pieces, and that you should not rely upon tricks, especially against a higher-rated player. Oscars tactic has holes so gaping that when one of his teammates asks a grandmaster about the possibility of using it, months later, the grandmaster will be tempted to dismiss him from the room for the mere mention of it. It makes little sense to Oscar, as well, but this is what made him try it. Hes never been one to surrender to the tyranny of the ordinary.

Across a hall, in the free-form holding pen for competitors and their families known as the Skittles Room, there are stacks of books about the Ruy Lopez and the Sicilian and the Nimzo-Indian and the Caro-Kann defenses, pages and pages of diagrams and complex notations that resemble an organic chemistry textbook. But this is not the type of knowledge that Oscar concerns himself with. Oscar prefers to accumulate his knowledge through experience. Hes never been big on studying lines of attack or complex variations or all those esoteric diagrams found in thick books of strategy authored by the masters of the game.