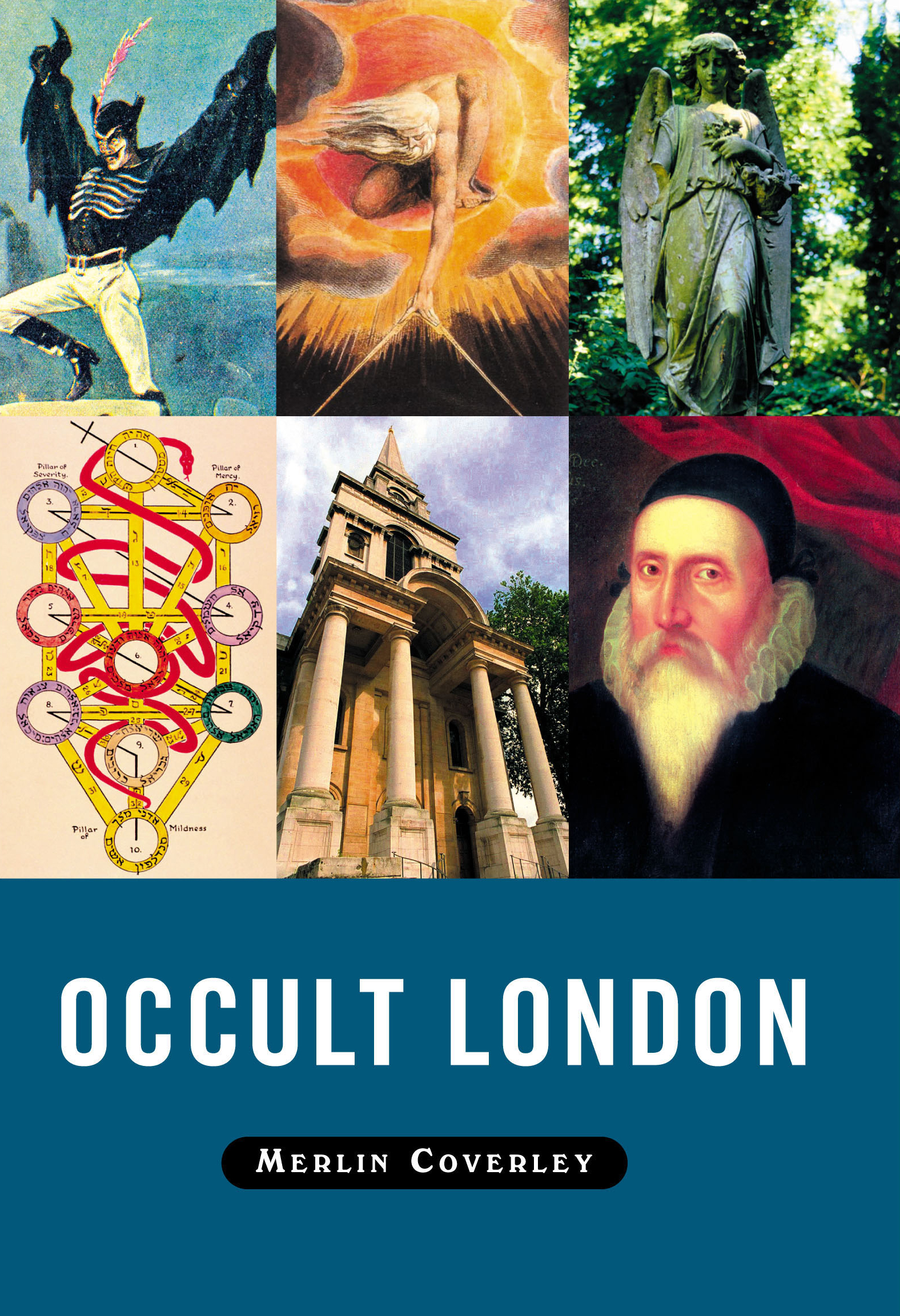

London, more than any other city, has a secret history concealed from view. Behind the official faade promoted by the heritage industry, lies a city of esoteric traditions and obscure institutions, of lost knowledge and hidden locations. Occult London rediscovers this hidden history, unearthing the secret city and its forgotten inhabitants. Encompassing a historical panorama from the Elizabethan age to the present day, we are introduced to the magic of Dr Dee and Simon Forman, the rise of the Kabbalah and the occult designs of Wren and Hawksmoor. Elsewhere we meet figures such as Spring-Heeled Jack and the Highgate Vampyre, and occult organizations from the Invisible College to the Golden Dawn.

Today a concern for such hidden traditions has returned and Merlin Coverley explores this revival of interest in the occult tradition, one that accords well with emerging New Age philosophies, the interest in Londons Ley Lines, in alternative histories and psychogeography.

Merlin Coverley is a writer and bookseller. He is the author of Pocket Essentials on Utopia, London Writing, Psychogeography, Occult London and The Art of Wandering.

Praise for Occult London

An interesting book covering Elizabethan, Occult London Eighteenth Century, Victorian and Twentieth Century London, looking at witches, witchcraft, Nicholas Hawksmoor, secret societies and more

- Zinegeek

a great little reference book, entertainingly written and full of fascinating information about the mysterious side of England's capital city.

- www.badwitch.co.uk

Praise for Psychogeography

A short, but valuable book - Daily Telegraph

A short guide to psychogeography for beginners - New Statesman

Although only 150-odd pages long, this is a complex book - Magonia Review of Books

Occult London

Merlin Coverley

POCKET ESSENTIALS

To Cate

The secret routines are uncovered at risk

& the point is

that the objective is nonsense

& the scientific approach a bitter farce

unless it is shot through with high occulting

fear & need & awe of mysteries &

does not demean or explain

in scholarly babytalk

Iain Sinclair, Lud Heat

Contents

Dr John Dee; Dr Simon Forman; Witches and Witchcraft: The Mary Glover Case

Nicholas Hawksmoor and the Rebuilding of London; Emanuel Swedenborg; Rabbi Falk: The Baal Shem of London; William Blake and the New Jerusalem

Spring-Heeled Jack; Madame Blavatsky and the Theosophical Society;The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn; Aleister Crowley

Ley Lines and Earthstars; The Highgate Vampire; Psychogeography and the Occult Revival

Introduction

Occult (adj.) Kept secret, esoteric; recondite, mysterious, beyond the range of ordinary knowledge; involving the supernatural, mystical, magical; not obvious on inspection. Occult (vb.) Conceal, cut off from view by passing in front, (usu. Astron., of concealing body much greater in apparent size than concealed body).

London is a city whose origins remain obscure and whose identity remains bound up with the mythical and the legendary, the hidden and the occult. In the absence of any solid evidence, Londons pre-Roman history remains a mystery, the most influential voice belonging to the twelfth-century cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth, whose History of the Kings of Britain seeks to explain the origins of Roman Londinium through recourse to the city of Troy and the figure of King Brutus:

Once he had divided up his kingdom, Brutus decided to build a capital. In pursuit of this plan, he visited every part of the land in search of a suitable spot. He came at length to the River Thames, walked up and down its banks and so chose a site suited to his purpose. There then he built a city and called it Troia Nova. It was known by this name for long ages after, but finally by a corruption of the word it came to be called Trinovantum.

As the story goes, Brutus, the Trojan great-grandson of Aeneas and descendent of Judah, established the city of Trinovantum on the bank of the Thames in c. 1100 BC. But it was much later, in 113 BC, that the city was refortified by King Lud who, having constructed the walls and towers, renamed it in his own honour as Caer Lud, the name gradually giving way to Caerlundein, Londinium, and finally London. Buried at Ludgate, the westernmost gate of the city wall, he is remembered today in the names of Ludgate Hill, Circus, Square and Broadway.

Geoffrey of Monmouths account was no doubt born of a competitive desire to provide London with a history as old and as grand as that of Rome itself. And these early myths and counter-myths, in which the more straightforward Roman history is welded to an exotic, but wholly unsubstantiated, strand of Celtic folklore, demonstrate the way in which Londons past remains a contested one, as new histories, both the official and the more unorthodox, continue to be generated. Indeed, in Tudor times, a new version of Geoffrey of Monmouths tale was to emerge, in which Brutus captures the two native giants, Gog and Magog, only to return them to London to be used as porters at the gates of his palace. Over time these two figures have themselves come to be seen as guardians of the city, their effigies frequently used to symbolise London in displays of civic pageantry, and today their statues can be found in the Guildhall.

Of course, any attempt to provide an exhaustive account of Londons occult heritage would result in a history as extensive as any of those official accounts that aim to capture the city in its entirety. For Londons occult history is less a chapter within a larger work than an alternative method of apprehending the city, albeit an unconventional one. Inevitably, therefore, this guide is forced to limit itself to an illustrative sample from Londons occult archive, a brief introduction to a subject whose mastery would require a lifetimes study. Regarding the occult not simply as a series of isolated episodes but rather as a continuous history which unfolds, largely unacknowledged, behind that of our everyday experience, I have chosen in this account to focus chronologically upon those historical periods in which the occult comes momentarily to the forefront of the public imagination, before returning once again to a position of obscurity.

From the Elizabethan era, in which the occult was often indistinguishable from the emerging New Science of the Enlightenment, to the occult reconfiguration of the city in the early eighteenth century; from the flowering of occult interest in fin de sicle London, to the occult revival that we are experiencing today. Throughout these periods, Londons history may be characterised as a tale of two cities, in which the rational faade of scientific and economic progress is offset by the existence of another city, governed by quite different imperatives. This other London, which exists behind or below the one which is commonly experienced, has provoked visions of the city celebrated by writers from Blake to de Quincey, Stevenson to Machen, as well as in the work of contemporary figures such as Peter Ackroyd and Iain Sinclair. And, in its exploration of this hidden city, Occult London may be read as a companion to my earlier contributions to the Pocket Essentials series, London Writing and Psychogeography , both of which involve a similar engagement with the Matter of London.

But when we talk of the occult, what exactly do we mean? Definitions seem to be as nebulous as the supernatural phenomena they purport to describe. The only point of unity appears to be an academic dismissiveness toward the occult itself and an uneasy mistrust of its practitioners: Claims for the ubiquity of occult influence on aesthetic culture are commonly received as allegations, reflecting scholarly fear of the occult. It seems to be widely believed that any contact with the occult is rather like contact with an infectious and incurable disease.